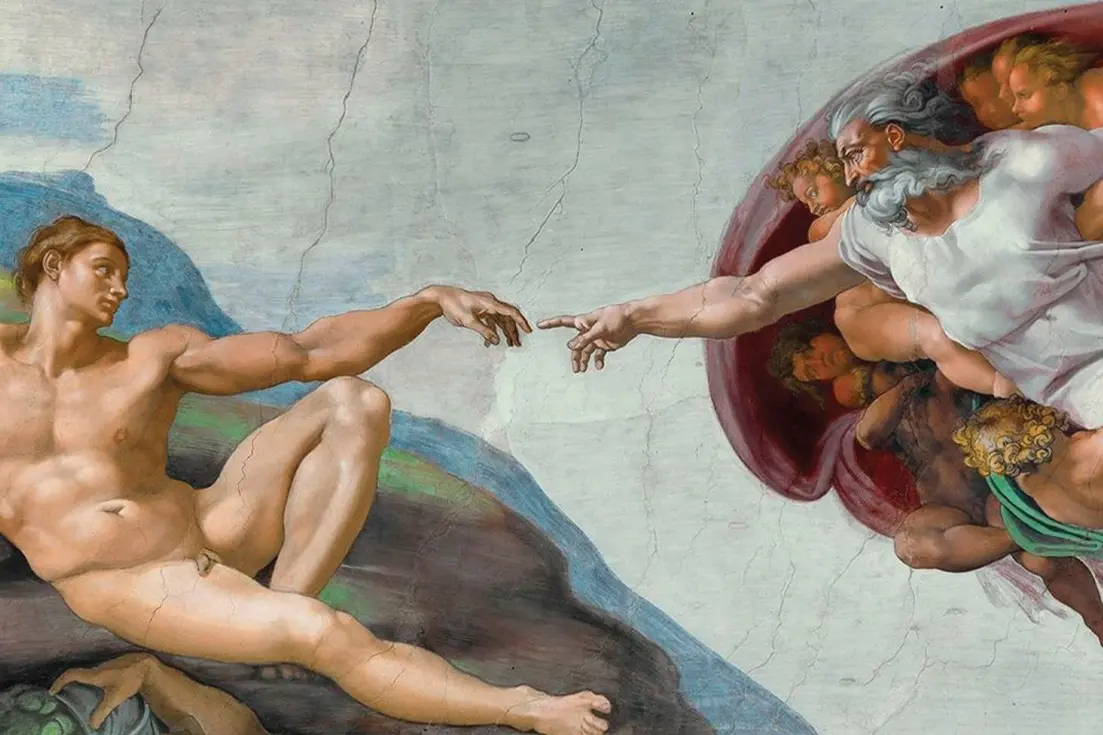

Science and religion have been in conflict since at least 1543, when Nicolaus Copernicus published his landmark work proposing that, perhaps, the earth might not be the center of the universe after all. Some scholars point to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution as the beginning of a paradigm shift in which society began to privilege science over religion. As recently as 2015, according to the Pew Research Center, nearly six-in-ten Americans still believed these two realms—that of subjective divinity and objective academia—often could not be reconciled. Still, that hasn’t prevented researchers—psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, and others—from trying to use scientific measurements to comprehend the value or purpose of religious experience. And according to Justin Lane, senior researcher at the Center for Modeling Social Systems, the science is clear: There’s a direct link between a person’s religion and/or spirituality and wellbeing.

That’s what psychedelic researchers at Johns Hopkins, New York University, and other prominent institutions are finding, too. In these clinical trials, investigators are using what’s called the “Mystical Experience Questionnaire” to determine the strength of people’s mystical experiences while tripping. They’re finding there’s a relationship between how strongly a person experiences qualities like “unity” and “transcendence of space and time” while on a psychedelic—and how much healing they receive from their trip, whether it be from depression, addiction, or another condition.

Lane, an Oxford-trained cognitive scientist and religion scholar, is not surprised by these findings. Regardless of what causes a mystical experience, he says, it often results in healing and profoundly shapes the rest of a person’s life.

But, he points out, we may often put a disproportionate amount of emphasis on moments of awakening or revelation. Sure, mystical experiences are therapeutic, but so are many other aspects of spirituality, from community to daily rituals. That, says Lane, is fundamentally important to understanding why religions from around the world, regardless of what they look like, serve a common purpose: to heal us.

DB: I’d like to start out by asking you to help me put the therapeutic, mystical experiences people have on psychedelics into perspective. What do you make of them?

JL: I think there’s a lot of evidence not just from psychology, but from anthropology, as well, that there’s a relationship between mystical experiences, wellness, and health. At [Johns] Hopkins, this measure they’re using, it’s been tested, it’s been validated. But it seems they’re tapping into just one dimension of the relationship between religion and health or wellbeing. It goes a lot further than mystical experiences as being caused by something like fasting or intense meditation. You also see a lot of relationships between nonspiritual aspects of religiosity, things like ritual experience or prayer, and wellbeing.

How do other aspects of spiritual practice contribute to wellbeing?

Things like ritual behavior, singing or creating movements together as a single body, lead to things like pro-sociality and greater levels of giving whereas mystical experiences aren’t always associated with those things cause they’re more internal.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Why is there so much emphasis, do you think, put on revelation or having some kind of divine experience?

In my own research, we surveyed a couple thousand people in four different countries, the UK, the US, Singapore, and India. We asked them how often they pray, how often they attend church, how strongly they identify as religious or not, and we also asked them if they had ever had an intense mystical experience and we found it was relatively rare. But when you do have those experiences, they can be formative throughout one’s life. These mystical experiences that I was looking at were almost entirely unrelated to psychotropic drugs, but the stories about the impact it had later in life were not so different from the stories you hear from people who were a part of the Good Friday Experiment, for example, where in 1962 people took psychedelic mushrooms on Good Friday and went to a church service. A lot of those people reported that that experience shaped their life, too.

If it wasn’t psychedelics, what caused most of the mystical experiences in people you interviewed?

It was often social relationships. Some of them were saying ‘oh, it was an intense experience of the death of a loved one or birth of a child or a wedding.’ It was these intense markers of someone’s life, but a lot of times it was in a social context with their close friends and they felt this overwhelming feeling of love or oneness with the people that were around them. You see this, for example, with people who are born again Christians during the time they were born again. A lot of times it happens at church retreats. Very rarely does it happen in isolation, and usually you’re around friends.

That’s interesting, because I think a lot of times people think of naturally-occurring mystical experiences as being caused by something like fasting or intense meditation.

That is a common belief. When we think of a mystic, we think of this old guy on a mountain or this idea of a yogi practicing Hinduism. While those are very legitimate ideas, and obviously there’s historical precedent for them, when we look at the vast majority of mystical experiences, they’re not being had in isolation, but together.

What do you think that says about human nature?

We are social primates and despite all our fancy smartphones and skyscrapers, at the end of the day, living in groups gives us resources, food, security, and shelter. It’s been that way for thousands of years. Being social is an integral part of our species. The fact that the way we connect with something otherworldly or divine is also a social experience almost seems to make more sense than the alternative.

Read: Why Feeling “Connected” Is Good For Your Health

I think it also reflects where we are socially and culturally. Singapore, for example, is a hyper- capitalistic society which is very conservative both morally and socially on a lot of issues. The use of any psychedelic is completely illegal by death. You’ll never see a Burning Man in Singapore. But people are still having these mystical experiences in church, you see people speaking in tongues where they can unleash. They feel this immense feeling of oneness, whereas all week they work eight to ten to twelve hours at a desk. It brings into focus why these particular churches are so attractive there, and I think when we look at the US, too, at conservatism in the South, you still see churches as being an integral part of people’s identities and experiences and it’s a way of bringing a sort of balance there. I don’t think we should think of events like Burning Man as that far removed from these churches. In fact, they’re both places where people get to unwind, to be both themselves and different from who they are in their nine to five jobs.

What would you say to a person who is lonely or depressed but just doesn’t believe in religion?

I recently had a conversation with an atheist organization. They asked me how they could create a long-lasting atheist group. I told them one way to do it is to use decriminalized drugs together, to have shared experiences with one another in a safe environment.

Like psychedelics?

Yes.

Why?

I suggested it because intense psychological experiences stay with you for the rest of your life. They activate a certain type of memory where you don’t remember what was said during the experience but you remember who you were with, so you remember that for the rest of your life.

What role do you see the psychedelic renaissance playing in religious practice moving forward?

I think psychedelics have been a foundation of religious and spiritual practice for as long as we’ve had something worth writing about. There’s a lot of people who suggest that books in the Bible were written with psychedelics and there are certain passages that make me think “yea, well maybe.”

Read: L’Chaim Psilocybin: How Psychedelics are Reigniting Judaism

Psychedelics give us a secular, new mechanism for bonding and having experiences that are out of the ordinary, so I would be willing to bet a fair amount that they are going to be a key part of religious and nonreligious practices moving forward.

What about all the people in the world who will never take one though?

I think it’s going to be a slow change, for sure, because it’s become engrained in pretty much all western cultures that the use of psychedelics is taboo and there’s no context for their use. When you look at societies that have traditionally used them, there’s always a context for them. In modern society, there’s kind of an underground, ritualistic context for how people take psychedelics, but it’s removed from more traditional religious contexts. At the same time that an interest is being revived in psychedelics, though, you have very serious medical research in nonreligious instances using them to deal with things like PTSD, for example. As these two different cultural shifts happen, they’re slowly going to start reinforcing themselves and I think it’s going to look similar to the cultural shift that’s happened with the use of marijuana. You can already see it happening in some places where they’re trying to change the laws around psychedelics.There are going to be some societies where it never will happen though. Like in Singapore, I don’t see it happening.

There’s obviously movement already in certain parts of the world around psychedelic reform: the United States, Canada, the Netherlands. How much of the world falls into that Singapore category though? How much of the world do you think will never see psychedelic reform?

The best way to decide who is going to make that change is to follow the money. As countries become more wealthy, they become more liberal. You see this in the United States, too. The poorer states in the United States are not the ones who are open to decriminalization or legalization. Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, they’re all wealthier states and they were the ones to lead the charge on cannabis. They seem to also be the states that are more open to decriminalization or legalization of psychedelics.

Interested in having a psychedelic experience, but don't know where to start? Get our definitive guide on trusted legal retreat centers, clinical trials, therapists, and more.