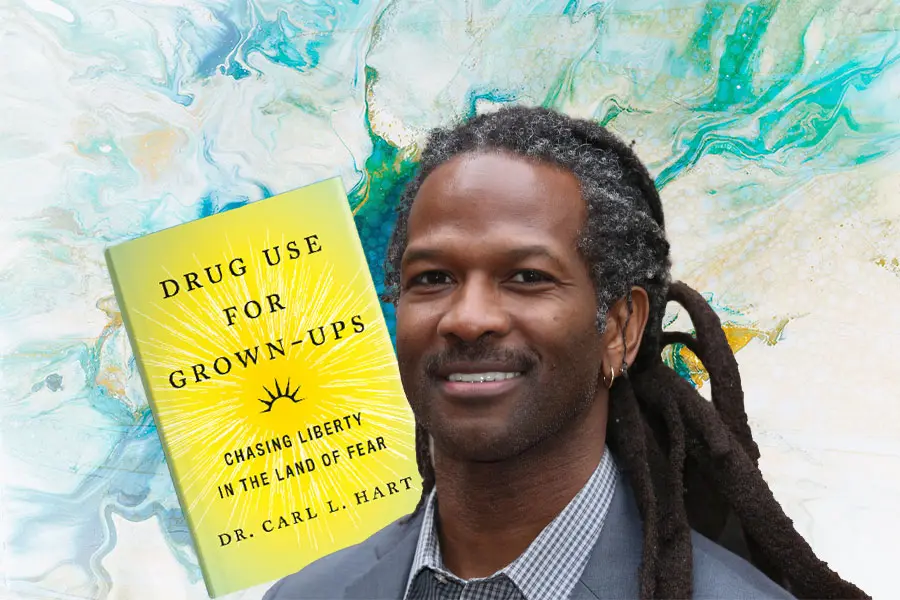

The War on Drugs is a massive failure. As neuroscientist and Columbia University Professor Dr. Carl Hart writes in his latest book, Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear, “the American taxpayer spends approximately $35 billion each year fighting this war, yet the drugs in question remain as plentiful, if not more so, than they were in 1981, when the sum total of America’s annual drug-control budget was a mere $1.5 billion.” The difference now, Hart describes, is that today, tens of thousands of people are dying from drug-related overdoses—with opioids being the “primary culprit.” But it’s not that simple, when the “opioid crisis” in particular is, in reality, “a crisis of data collection and reporting.” In this account, Hart digs below the surface to re-evaluate the American relationship to drugs, while shedding light on his own personal relationship to drugs, as well. Both captivating and controversial, we caught up with Dr. Hart to talk about drugs and parenting, policy, addiction, and more.

DB: Everyone’s excited about your new book. What’s one thing you really want readers to glean from it?

CH: The thesis of the book is very simple: It’s about liberty so long as you don’t disrupt other people’s ability to pursue their liberty. I want people to understand that liberty and the pursuit of happiness are protected in our founding document. It’s the core of being American.

In the book, you’re very open about your own drug use. What’s that like, coming out of the drug closet, as a professional and as a parent?

That’s a big question I have to face and I still struggle with it. The most important point for me is that I live like the man that I claim to be, and that means that I have to think about how my children see me. They know that I take care of my responsibilities with them and that I care about our broader community. They see people suffering, being vilified, and persecuted for being labeled a drug user—and they know their father is standing up on behalf of those people, who have been cast away in society, and they feel good about it. As long as they feel good, I feel good. My primary concern is my family, and my children in particular.

As a kid, I remember my own parents had to tackle this question, too, in regard to their cannabis use. I think before he thought I would remember, my dad would sometimes smoke “herb” in front of me before I was old enough to register the observation. How do you handle this with your own kids?

My drug use is still personal and private. It’s like asking, “have your children seen you have sex?” I’m 54 years old, I’m not a child, and so I engage in grown-up behaviors in which my children will not observe me. I don’t observe them doing certain things, either. I only care about them being safe and taking care of themselves.

In particular, it might be surprising for the audience to learn about your recreational heroin use. At the same time, it’s a good opportunity to model a responsible, healthy relationship to drugs (be it heroin, cannabis, or even alcohol). How do you reconcile this with the query from those who might bring up the argument that trying drugs, like heroin, will automatically lead to addiction?

There’s a lot in that question, so let’s unpack the first major point: How do you model responsible drug behavior? First of all, I don’t think of drug-taking behavior as abhorrent or unique. It’s just behavior. How do you model behavior? Well, what do responsible people do?

They keep their appointments, they make their obligations. And with drugs, you set aside time for that activity, and you know how long it takes for you to engage in that activity, and once it’s over, you carry out the other responsibilities you have. It’s not different from any other behavior—this is the big lie that’s so hard to undo.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

And this notion that one hit and you’ll become addicted is nonsense: That point is always overstated. If a person is already irresponsible, then if they take heroin, they might also be irresponsible with their heroin use. How responsible a person is will tell how well they handle those other behaviors; it predicts how well they will do heroin or pay their bills. So their drug behavior, whether heroin or cannabis, is not unique from other behaviors.

Read: Where Will Psychedelics and Other Drugs Be Decriminalized Next?

So when we talk about drug legalization and people ask—”what about the addicts?”—what do you say?

In the U.S. and around the world, when we think about addiction, people tend to blame the drug—the substance, itself—for causing addiction, and that’s a limited and inaccurate approach. The majority of people who use any drug are not addicted: That tells you that you have to look beyond the drug with people who meet criteria for addiction. You’ll find that people who already have psychiatric disorders, or limited economic opportunities, are more likely to have the criteria for drug addiction. It’s not the drug that you have to focus on, but those other factors, regardless of whether they’re using the drug or not.

Part of the problem with the drug discussion is that addition has hijacked the conversation, such that we only talk about drug addiction when talking about drug use. It’s like only talking about car crashes when we talk about automobiles. It’s ridiculous. So we have to change that, and that’s what I’m trying to do. If when we talk about drug use and we gave addiction proportional treatment of the topic, it wouldn’t be talked about that often. It’s a concern, but the reason people are addicted is not because of the drug.

When we think about addiction, people tend to blame the drug—the substance, itself—for causing addiction, and that’s a limited and inaccurate approach. The majority of people who use any drug are not addicted: That tells you that you have to look beyond the drug.

So if the majority of drug users are not problematic drug “abusers,” how did drug use and abuse get conflated?

When we think about the addiction narrative, the reason many of these substances are prohibited is American racism. One of the primary motivating factors behind alcohol prohibition was dislike of the Germans; remember this was around the time of World War I. When we think about cocaine, to vilify it, its negative effects were associated with Black people. When we wanted to vilify opioids, we paired it with the Chinese. All of this media hysteria was inaccurate—lies and misinformation. By connecting horrible acts with those groups and the drugs they used, the media reports and politicians gained standing. They oftentimes used white women as the object of their protections, so they were protecting white women and children from being corrupted with these drugs. Once they were corrupted, they would intermingle with those other racial groups—so they really tied the potential for addiction with these drugs, hoping to make people fearful of taking them in their quest to protect primarily white women. That’s how we have this connection.

Read: How Anti-Racism is a Form of Psychedelic Harm Reduction

But for those who do struggle with problematic drug use, how should we as a society handle it? And how do we define drug abuse, versus drug use, to begin with?

We define it as when people have certain symptoms in which they have disruptions in their functioning: They may not be meeting their occupational obligations, their family obligations, or other obligations. They may be actively trying to quit and having a hard time. They may experience some negative effects from their drug use, whether physiological or social, and they are disturbed by all these symptoms.

They, themselves, must be disturbed by these symptoms. Such as, you may engage in behavior and your significant other may not like it, but you may not be troubled by the behavior or it may not actually be a problem. So the person, themself, must be distressed by these symptoms, too. The person’s own perspective is important.

In our country, each of us are guaranteed life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We often think about those rights as guarantees in jingoistic terms, as opposed to unpacking how serious and noble those ideas are, and so I’m trying to remind people that everyone has those unalienable rights. That means they can’t be taken away from them, as long as they don’t disrupt other people’s ability to pursue their rights.

If I had a relative who had a drug problem, I’d be hard pressed to find a place in the U.S. where I would send them—in large part because, too often, those places focus their energies on the drug itself, as opposed to those other psychosocial factors, such as whether that person has housing, health care, or gainful employment (that is, employment that would be appropriate for their age, education, ability to support a family, all those things). Does the person have other psychiatric illnesses or problems going on? All those factors are far more important than the drug itself. And too often the drug rehab centers focus on the drug itself and miss the boat.

In your book, you talk about how the opioid crisis has been misrepresented in the media. Can you elaborate?

For one, why are we missing the boat when we talk about opioids? We are getting it wrong because there is money in getting it wrong. There are grants now to deal with the so-called opioid crisis. This is an economic strategy, as opposed to making sure people have gainful employment. Police organizations get grants. NGOs get grants to deal with opioids. Coroners, medical examiners, everyone is getting money to deal with it. Everything they do, they see opioids because that’s where the spotlight is shining—if you’re looking for something, you’ll find it.

When we think about the addiction narrative, the reason many of these substances are prohibited is American racism…By connecting horrible acts with those groups and the drugs they used, the media reports and politicians gained standing.

But this is how they’re getting it wrong: A few weeks ago, I got a phone call from a mother whose child had died from what was described as an opioid and cocaine overdose. The mother sent me the toxicology report, and I looked at the blood levels, and there was a small amount of fentanyl—not enough that would cause an experienced opioid user to overdose—and also a very small amount of cocaine (five times smaller than what we typically see in the lab). Yet, they called this an opioid and cocaine related death, and while I don’t know how this person died, the evidence did not support that. That’s the case with many of the deaths around the country. What it means is that we’re not getting to the bottom of what’s going on. That is a shame because then we can’t help people. So that’s irresponsible.

I think that if we really were concerned about people’s potential to overdose from opioids, we would first of all make sure the quality of the supply is good. One way to do that is to set up drug checking centers, where people submit small amounts of their drug and get a printout of the chemical composition and explanation of what it means. They do this in Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Austria. We don’t do it in our society, yet we say that we care about people. If we did care, we would implement this, and also tell people to be careful if they’re mixing opioids and other sedatives. People don’t think of alcohol as being a sedative, they think of it as background noise. If you’re drinking alcohol and you’re an inexperienced opioid user, you should not do both together.

Since we focus on psychedelics for DB, let’s break down the pathology of psychedelic exceptionalism—the idea that psychedelics (and cannabis) may be inherently better than other drugs.

I use the example of PCP and ketamine. PCP would be classified as a psychedelic, but we don’t like to talk about that, in part because police have chosen to take that substance and vilify it, and so the psychedelic community doesn’t want their substances tainted with the reputation of PCP—even though PCP and ketamine produce almost identical effects. I would like to make sure that other people’s rights are protected just like my rights are protected because if their rights aren’t protected, then my rights aren’t either. Psychedelics are just chemicals, just like other classes of drugs. We are all seeking to alter our current state of being, and that is a simple thing. The flowery vocab we use to explain what we’re doing doesn’t matter.

What would America’s ideal relationship to drugs look like? What’s your stance on decriminalization versus legalization?

I think Portugal has let us down in some respect. It’s been 20 years of decriminalization; come on already, it’s time to legally regulate. Decriminalization is a great first step, but it doesn’t deal with the issue of drug contaminants. Drug contaminants are the real concern when people don’t know what they have in their substances. Drug regulation would make sure there’s legal quality control, just like there is with alcohol. During prohibition, people were killed because of tainted alcohol. Drug legalization would take care of that. That’s where I want society to go.

If people are worried about big pharmaceutical companies monopolizing the regulated drug market, then they should reconsider our economic system of capitalism. That has nothing to do with drugs. It’s like, have you lived in America? That’s what we do. Whether it’s Nike or Coca Cola, that’s what big companies do under capitalism. Why should this be any different?

Anything else you want to add?

I just really want to emphasize the promise of the nation—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—and how that’s inconsistent with the practice of having these draconian drug policy measures that are locking people up for pursuing these fundamental rights that we guarantee.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.