The author would die two days after publishing his first and last novel. He was 29. It’s usually the first thing that’s revealed. April 30, 1966, the day of his 21-year-old wife’s birthday, Mimi, the younger sister of folk star Joan Baez. That’s also worth a mention.

Richard Fariña was on the cusp of fame the day he flew off the back of a friend’s motorcycle and died on impact in California’s Carmel Highlands. Hours before, he was at his book release party where he had signed copies with one word: “Zoom!”

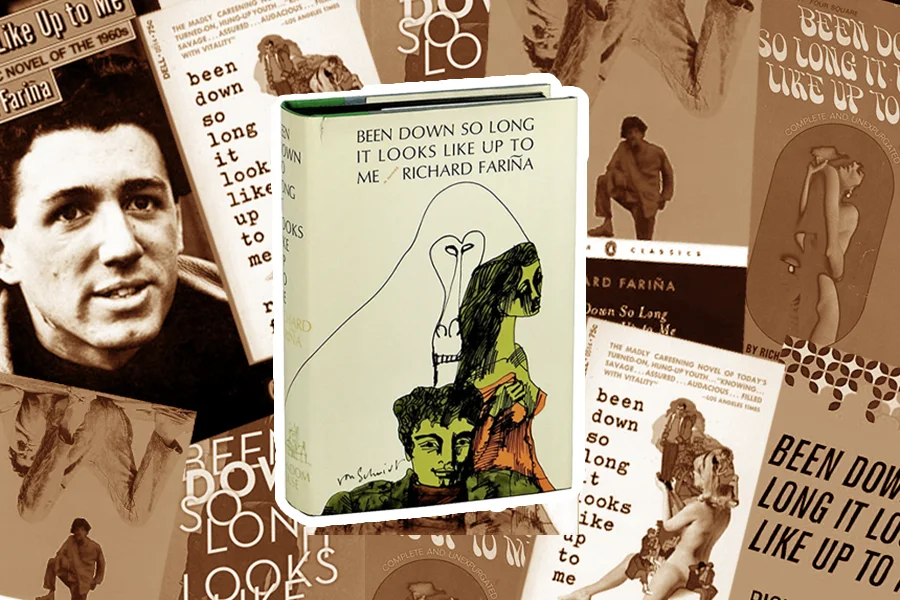

The paperback version of his book, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me, is still in print, published as a Penguin 20th-Century Classic, but aside from obscure namechecks from The Doors and Nancy Sinatra to Earl Sweatshirt and Drake, Fariña’s book remains the counterculture’s best forgotten literary one-hit wonder. Belonging to neither the Beats nor the Hippies, somewhere between the varsity genre and psychedelic travelogue, Fariña’s debut has all the faults of a hungry 20-something’s first novel—brown humor in purple prose by a green author. Among rare readers, no one can agree on its point or purpose, and it’s either hailed as “the finest example of the American campus novel ever written” or thrown against the wall (as was Hunter S. Thompson’s alleged reaction).

Fariña was one of America’s most promising young writers and musicians in 1966, but Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me was never meant to be his magnum opus. Its composition spanned two years, two continents, two marriages, and two careers—the second as a rising folk singer who had just played the Newport Folk Festival and Pete Seeger’s TV show. In his brief adult life, Fariña assembled a cast of famous supporting characters that featured Carolyn Hester as his first wife, Thomas Pynchon as best man at his second wedding, and Joan Baez as sister-in-law with her lover Bob Dylan as his narrative foil.

What’s kept the book alive is Fariña’s untimely death, but when paired with the author’s own biography, which he often treated as fiction, the lyrical prose reads just as transgressive and generationally damning today as Kerouac, Kesey, or The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. More than a cultural artifact or generational badge, the book’s lack of focus has turned out to be its greatest strength half a decade later.

A picaresque roman à clef set in 1958 at a fictionalized Cornell University, the novel’s Homeric antihero is a Greek swashbuckler named Gnossos Pappadopoulis who’s just returned a stranger in a foreign land determined to quit his old ways. “I’ve been on a voyage, old sport, a kind of quest, I’ve seen fire and pestilence, symptoms of a great disease,” Gnossos says. He’s haunted by literal and figurative bad trips and anesthetizes his expanded mind with opium cigarettes and a Hamlet-like brooding, not on mortality but immortality, youth’s greatest delusion. “I am invisible, he thinks often. And Exempt. Immunity has been granted to me, for I do not lose my cool.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

He’s your morning eye-roll at Intro to Psych. Holden Caulfield on hallucinogens. A posturing protohippy who carries a rucksack of feta cheese and silver dollars—no filter, saturnine, borderline-rapey Heathcliff who doesn’t do himself any favors and won’t do you any either. Readers have no idea if Gnossos was this rakish and jaded before his Byronic Hero’s Journey, only that his wildcard reputation precedes him.

A cabal of student dissidents plots to overthrow the current administration and its policies against coeds-only curfews, seen as a direct attack on students’ sex lives. They recruit Gnossos’s cult of personality for their junta and incite campus unrest through newspaper op-eds and library strategy meetings. Gnossos resists their Poli Sci experiment, but his arc from apolitical heretic to reluctant demagogue is propelled, of course, by romance.

At an off-campus orgy, a pet monkey named Proust who “digs lysergic shit” triggers Gnossos’s pithecophobia and sends Kristin, “the girl in green knee socks,” straight into his arms. A kaleidoscopic test of Gnossos’s faulty moral code and noxious sense of self fails and he ends up with the clap, a fate almost as bad as the denouement’s fatal Havana spring break trip and academic mutiny.

In Athené, highways are a “melting stretch of road.” Paintings become “liquid metaphors dipping away into neutral depths and plans, looming forward again, threatening the surface of the canvas.” Hangovers “look like spoonfuls of death.” Feces is treated as art with “secret cellular knowledge etched by the insides, trying to tell us something.” And falling in love is “a consolation. Like a sideshow panacea for symptomatic ills, it soothed anxiety, pain, and doubt; eased fear and insomnia, purged the more accessible demons, and apparently acted as a mild laxative.”

Gnossos hunts for undergraduate enlightenment not in the classroom but in mescaline, Eastern religion, backpacking, and multiple coups d’état. “Nothing he tries works,” novelist Thomas Pynchon writes in the book’s introduction, “but even funnier than that, he’s really too much in love with being alive, with dope, sex, rock ‘n’ roll—he feels so good he has to take chances, has to keep tempting death, only half-realizing that the more intensely he lives, the better the odds of his number finally coming up.”

The book was as much a portrait of the artist as junior iconoclast as it was an extension of the fakelore Fariña had been spinning for years. The famous and famously reticent Pynchon met the author around the same time the novel takes place, at Cornell in ‘58, and lends credence to the book’s heavy autobiographical material. “It seemed then that Gnossos and Fariña were one and the same,” he writes of an early manuscript. The university’s in loco parentis stance, the reactionary student demonstrations, the characters, the irrational fear of monkey demons—Pynchon remembered it all.

READ: These Tender, Surreal Dioramas are a Study of Psychedelic Love

Born to an Irish mother and a Cuban father, “he was blessed, and knew it, with a happy combination of heritages,” Pynchon writes of his friend, “a typical expression on his face was a half-ironic half-smile, as if he were monitoring his voice and not quite believing what he heard. He carried with him this protective field of self-awareness and instant feedback.” Polite and gregarious, Fariña was a confident raconteur and floated among social circles with intimacy and ease. And he was smart in the two best categories: books and people.

Fariña also had a metal plate in his head, slept with a loaded .45 under his pillow, joined the Irish Republican Army, and ran guns into the Sierra Madres for Fidel Castro. Or so he said. The Brooklyn native was skilled in the art of the re-brand: asthmatic choir boy, Regents Scholar, student rioter, English major, IRA mercenary, poet, Cuban rebel, copywriter, tour manager, beatnik, author, singer-songwriter, outlaw, husband, gadabout, man-child.

Much of what we know about the guy comes from David Hajdu, author of Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña and Richard Fariña. “It was a perception of greatness that he was after, and the way there was secondary,” Hajdu tells me. “Being a novelist was very much the way to do that at this time.”

Fariña’s blind ambition was a red flag in some inner circles. He was eager and silver-tongued, a Svengali or Jay Gatsby; either way, an outsider. He used his wit, good looks, and habit of hyperbole to ingratiate himself into certain scenes du jour. He dropped out of college for a brief Mad Men phase writing ad copy for Shell Oil, but soon found his way to the White Horse Tavern in Greenwich Village where he began riding the crest of the 1960s folk music wave.

He married folk singer Carolyn Hester after knowing her for 18 days and became her de facto manager. Two years later, they divorced, and he was sharing a “rustic cocoon” with his teenage bride, Mimi Baez, her famous sister, Joan, and her on-and-off-again boyfriend/collaborator Bob Dylan, a younger and more accomplished (celebrity) frenemy of sorts. The two got matching gold hoop earrings one day, and talked shit about the other’s art the next. Hajdu paints evocative scenes of the two couples nestled up in love shacks from Northern California to Upstate New York, sharing pages and joints alongside competing egos and wandering eyes.

Both Dylan and Fariña were aspiring artistes, interested in merging forms like rock and literature, poetry and folk. Both hid behind a fiercely protected self-mythology, but next to Dylan’s trademark cool guy laconicism, Fariña became the tryhard. “I think he was creating himself in a way where I could kind of see the strings, whereas in Dylan’s case, I couldn’t see the strings,” one folk musician puts it in Positively 4th Street. “Dick was like ‘Look at me—here I am. Dig me!’ Dylan was like, ‘Look all you want. You’ll never see me.’”

Fariña began recording and touring as a folk duo with Mimi but still clung to his literary dreams, publishing short stories and reported essays. He learned the four-stringed Appalachian dulcimer—and is often credited with popularizing the instrument among West Coast musicians—and turned his Romantic poems into “Pack up Your Sorrows” and the protest song “Birmingham Sunday.”

Hajdu estimates that Fariña finished Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me in two years, between 1961 and 1963, taking as much time to find a literary agent, Richard Mills, and sell the book to Random House. By the time it was published in April 1966, Fariña was onto the next, somehow having convinced Joan Baez to let him produce her experimental rock album that she later abandoned after his death. He also had been planning a memoir about those salad days in the early ‘60s spent with Mimi, Joan, and Bob.

Youth is wasted on the young, but not with Fariña. He didn’t have the luxury of waiting to be discovered; he was born with something to prove.

Today, we’ve replaced the mendacious fake-it-til-you-make-it-ness of the American Dream with the idea of the grifter—Anna Delvey, Caroline Calloway, The Tinder Swindler, etc.—scammers, not dreamers, who manipulate and study and imitate to jailbreak their fates in pursuit of money, status, acceptance, or all of the above.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Hajdu suspects Fariña in 2023 wouldn’t have to write a sentence, let alone a novel. And though the book is an ode to psychedelia in style and content, Hajdu says Fariña wasn’t as concerned with the stuff in real life. “Mimi said they tripped a few times,” Hajdu says. “It wasn’t, by her account, a significant part of the way that they lived or the way they thought about life. It was really separate from their artistic process.”

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me is awash in allusions to the era’s preoccupation with authenticity and substance. Gnossos and his terrible phantasms reflect a generational nightmare: disillusionment at what’s discovered beneath the slick surface of post-war America. First loves become first STDs, and spirit quests are fool’s errands. More than literary stand-in, Gnossos is at his best when voicing Fariña’s id, a device to plumb his contempt for the WASPs, frat boys, ivory towers, and gatekeepers he sought to impress. The darkest scenes aren’t when the protagonist’s fighting a wolf in the snowy Adirondacks or witnessing an atom bomb but when he enacts revenge fantasies against those who deny or betray him.

“The Class-A essence of superficial cream spun centrifugally upward by the silently churning forces of a blue-eyed society,” writes Fariña in an early fraternity dinner scene, which ends with blacked-out Gnossos wielding racist insults and an enema bag across the table.

He coerces sex and commits non-consensual condom removal. Female descriptors are reduced to “dyke” and “Radcliffe Muse.” The one time he lets his guard down, it’s a honey trap. “Avoid my gaze, ladies, for you read the wish well enough,” Fariña writes. “Care to mount a maniac before you marry your lawyer? Some Gnossos seed, in case your man goes sterile from martinis.”

Gnossos does, for a second, ponder the post-grad life: “Not enough work being done on hallucinogens, for instance, and the mechanics of probability, man, they haven’t even dented it yet.” But this is still Odysseus in denim, and before he can graduate, his hubris is rewarded with a draft notice. Gnossos wasn’t Fariña’s alter ego; he was his deepest fear.

After Fariña accidental death, Mimi continued making music and remarried but maintained her first love “was an impossible act to follow.” She was 56 when she died of lung cancer in 2001. Her sister Joan Baez, a lifelong activist, is still folk music’s reigning queen. Pynchon is one of the most celebrated and prestigious American authors alive. And Bob Dylan, who had his own life-altering motorcycle crash three months after Fariña’s, is regarded as the greatest living poet with a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Fariña remains the superstar that never was. As much as he tried, he couldn’t pull off the mysterious and inscrutable act. Fariña’s greatest sin and superpower was that he wanted to be liked. There is no Trojan Horse in Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me—his thesis is on the first page in the epigraph: “I must soon quit the Scene…” Benjamin Franklin in a letter to George Washington (March 5, 1780).

*This article was originally published in DoubleBlind Issue 9.

Interested in having a psychedelic experience, but don't know where to start? Get our definitive guide on trusted legal retreat centers, clinical trials, therapists, and more.