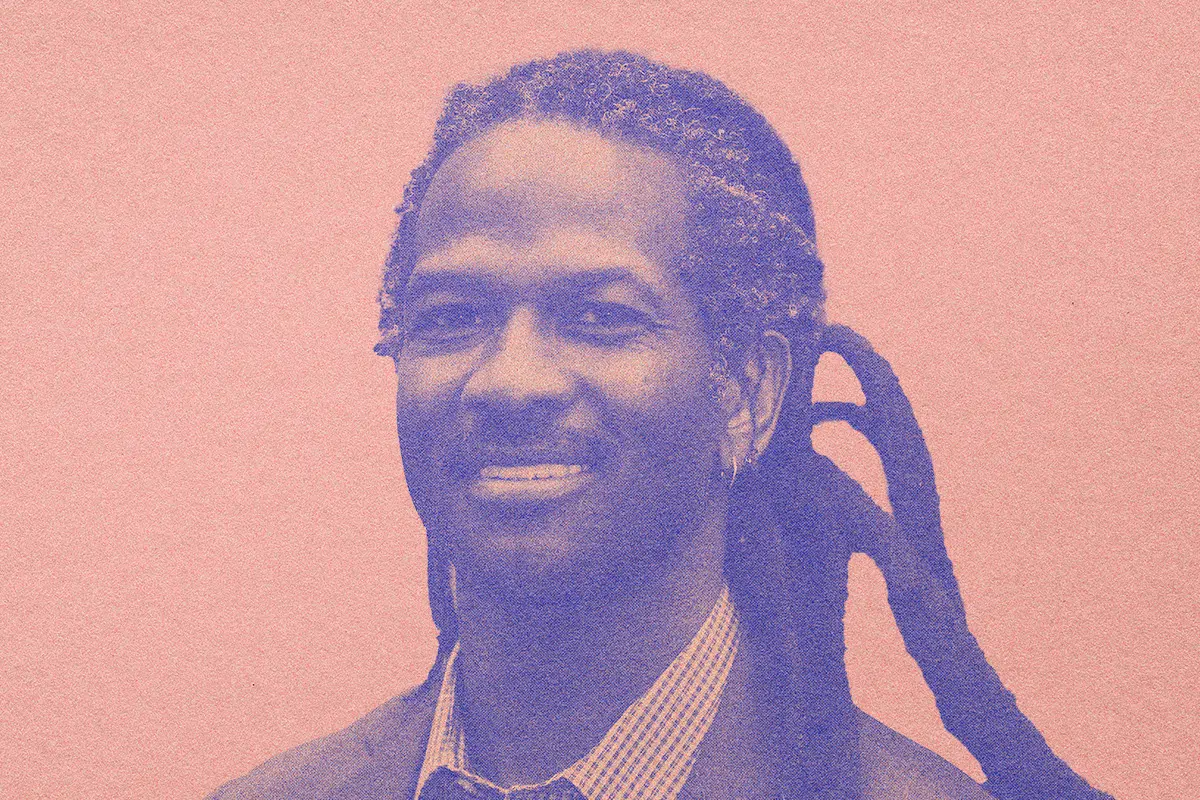

My heart skips a warm beat—and also aches a bit—each time I visit Brazil. I was recently there as part of my book tour promoting Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. Large audiences in multiple cities openly greeted the evidence supporting my arguments. Even those who were not ready to fully embrace my recommendation to regulate the sale and use of sought-after drugs, just as we do with alcohol and tobacco, engaged in a grown-up conversation. My faith in people’s ability to reason and use logic when discussing drug-related issues was revitalized.

On the eve of returning to the United States, my wife Robin and I went to an Ipanema pharmacy, seeking a COVID-19 test prior to traveling. Our friend Julita, who is white Brazilian, accompanied us to surmount the language barrier. A delightful and efficient, young white pharmacist immediately assisted us. She quickly began completing the requisite demographic forms, even correctly noting Robin’s race, white, without asking. But when the race question arose on my form, this self-assured professional abruptly paused like a coyote caught in headlights. Turning to Julita, she sheepishly asked in Portuguese, “what shall I write?” The puzzled look on Julita’s face elicited a preemptive response, “You know, there are people who don’t like to be called Black.”

In Brazil, just like in many places, race is a tricky and sensitive subject with far-reaching social ramifications. The lines demarcating racial boundaries, at least to an outsider, seem blurred but unyielding. For example, a large proportion of the population have indigenous, African, and European ancestry. This makes it difficult to categorize people into neat racial groups. What is clear, however, is that Black Brazilians make up more than half the general population. Yet, their status at the bottom of the country’s racial hierarchy is conspicuous and unequivocal. In contrast, the white minority are firmly positioned at the top.

Read: Why All Drugs Should Be Legal

According to Julita, the pharmacist’s question was motivated out of twisted kindness. She had observed that I was an American tourist and perhaps an “important” person. So naturally, she figured, I wouldn’t want to be included among one of the country’s most vilified groups: Black people. She generously offered me an opportunity to self-identify as anything other than Black. In her mind, she was doing me a solid. I could quietly recoil into the “racial closet” without consequences. Never mind that there is nothing ambiguous about my racial background. I am unmistakably Black. And ultimately, this is precisely what I communicated to her.

Still, this incident got me thinking about commonalities shared by marginalized groups, including drug users. It also made me face why it’s important to align myself publicly with the downtrodden. The stories told about these groups are often simple, inadequate and just plain wrong. A pervasive stereotype about young Black Brazilian males is that they are violent and dangerous. Many are also viewed as drug traffickers and drug users. What’s worse, these biased portrayals often comprise callous political rhetoric and are translated into draconian policies and practices, which results in further dehumanization.

What kind of man would I be if I didn’t stand up on behalf of marginalized people? This question becomes even more pressing when I consider my own experience as a Black man in the United States, because it mirrors the situation faced by my Brazilian brethren. Authorities in both countries are adept at using drug-related issues to denigrate and subjugate the poor and Black people. Thus, I can no more deny my drug use than I can my Blackness. Hiding from either is an abandonment of my own humanity and the humanity of others. These are people, just like me, simply trying to live a life worth living.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

I recall the moment when I decided to get out of the drug-user closet. It wasn’t a decision taken lightly. At the time, I was starting my second year as department head and my youngest child was only sixteen. I knew that merely being identified as a drug user could have had grave repercussions on my career and child.

But in July 2017, as part of the prep procedures for my colonoscopy, I was being asked routine questions about my drug use. I had already acknowledged infrequent alcohol and cannabis use. The nurse, then, asked, “Do you use other drugs?”

“Should I be honest,” I wondered? I had always thought of myself as an honest man. But serving as department head was turning out to be a distinct lesson in the gaping difference between self-perception and reality. For example, the role required me to play the faculty recruitment game. I negotiated with potential new faculty hires in hopes of bringing them to Columbia. Despite the fact that nearly all had applied for a job with us—and some had even received an offer from us, many had no intention of leaving their current positions. It was just a game. It was played to get a Columbia job offer that could be leveraged to obtain more money, more lab space, or something else from their own institutions. It was an off-putting game, a dishonest one, too. But I was a player, albeit a reluctant one.

Now, I was being asked to play another game: the drug lying game. I was expected to lie about my current drug use, especially if it included villains like heroin or methamphetamine. Past drug use, on the other hand, was excused and could be honestly disclosed. It’s perfectly fine to acknowledge, for example, having previously used heroin as a “youthful indiscretion.” It’s also acceptable, and even preferred in some circles, to once have had, say, a heroin problem but kick it, so long as you now preach the “heroin horror” gospel.

Read: Inside the Psychedelic Exceptionalism Debate

The drug lying game often requires us to accept baseless notions about certain drugs. Heroin, for one example, is said to be banned in the United States because of its inherent dangers. By this logic, heroin use is intrinsically more dangerous than other legal activities, including tobacco or gun use. In the United States alone, each year there are more than 450,000 deaths attributed to tobacco smoking and more than forty thousand gun-related deaths. In 2017, heroin-involved deaths reached an all-time peak at just over fifteen thousand. This number is well below those associated with tobacco and gun deaths. It’s also important to point out here that the phrase “heroin-related deaths” does not mean that heroin was the cause of death. It simply means that it was found in the body of the deceased. In most cases, multiple substances are found in the body of the deceased, and the concentrations of these drugs are often not determined. To be clear, I am not advocating for further restrictions on tobacco or guns. Rather, I am demonstrating that stories we tell about heroin use being inherently more dangerous than tobacco or gun use have no foundation in evidence.

Back in the colonoscopy exam room, the nurse awaited my dishonest response. I couldn’t do it. I was tired. I was tired of being dishonest. I could no longer remain silent in the face of childish narratives about drug users that caricatured them almost exclusively as irresponsible, troubled souls. So, I divulged the full extent of my current drug use, which included cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, among others. Once the nurse got over her initial surprise, I had my colonoscopy without a hitch.

I recognize that disclosing my drug use publicly might be met with hostility by some. Drug War profiteers may even try to besmirch my reputation, saying I am an addict merely because I report using one or more vilified drugs. This is a desperate ploy. I have never met criteria for drug addiction, although this fact is irrelevant for evaluating the soundness of the arguments put forth. We would not label a person an alcoholic simply because the individual drinks alcohol periodically.

The point is: Drug use does not equate to drug addiction. To meet the most widely accepted definition of addiction—the one in psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)—a person must be distressed by their drug use. In addition, the individual’s drug use must interfere with important life functions, such as parenting, work, and intimate relationships.

Another important fact is that most drug users will not become addicted. That’s right, 70-90 percent of people who use even the most maligned drugs such as crack cocaine or heroin are not addicts. Thus, if most users of a particular drug do not become addicted, then it would be irrational to blame the drug for causing addiction. It would be like blaming food for food addiction.

In the end, I know I did the right thing by coming out of the closet. Sure, it’s risky, even frightening. But there are always risks when fighting to right society’s wrongs. I pity the person, particularly so-called “allies,” who fails to act in the face of injustice merely because there are risks. Remaining in the closet about my drug use—or anything that matters—is cowardly, dishonorable. I want no part of such games. Too much is at stake, for too many.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.