When Denver voted to deprioritize the enforcement of laws regarding the possession of psilocybin mushrooms in May of 2019, a flurry of cities across America followed suit. Although the movement has garnered many successes within individual cities and counties, widespread confusion about the differences between “deprioritization” and “decriminalization” still exists. This became a notable issue when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed Resolution #220896 on September 6. Despite the fact that the media framed this non-binding resolution as another victory for San Francisco and the broader decriminalization movement, it’s not quite that simple.

…But Didn’t San Francisco Decriminalize Psychedelics?

Despite what its proponents and news articles have claimed (including an article put out by DoubleBlind), Resolution #220896 did not technically enact decriminalization within the Golden City. Specifically, the text of the resolution states that the SF Board of Supervisors “urges” the city’s law enforcement organizations to make the “cultivating, purchasing, transporting, distributing, engaging in practices with, and/or possessing” psilocybin, DMT, ibogaine, and mescaline-bearing cacti “amongst the lowest law enforcement priority for the city.” It does not, as the resolution’s co-sponsor Supervisor Dean Preston said in a press release, “put San Francisco on record in support of the decriminalization of psychedelics and entheogens.”

The Resolution, instead, requests that local law enforcement organizations deprioritize the laws related to psychedelics. But it’s not clear yet whether that will hold any weight with the city.

In my opinion, claims that San Francisco decriminalized psychedelics amount to more than misinformation—they endanger marginalized communities that continue to be targeted by law enforcement organizations. Given that poverty, racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, and other factors impact the mental health of marginalized individuals, these folks may turn to psychedelics thinking they’re in the clear to possess them when it’s not certain what the consequences would be if they are caught.

We can look to Denver as an example. The Denver Psilocybin Mushroom Initiative, which passed in 2019, also made the personal possession and use of psilocybin mushrooms by adults a low law enforcement priority. That means that possession and cultivation are also not fully decriminalized in the city. Police have continued to seize mushrooms when investigating other crimes in recent years. They’ve arrested around 59 people per year in cases that involved the seizure of mushrooms—around the same amount before the initiative passed, according to data from the Denver Police Department. The number of cases related to psilocybin and psilocin filed by Denver’s District Attorney has fallen since the ordinance went into effect in 2019, but there were still 20 cases filed in 2020.

Proponents of Denver’s Initiative, such as initiative organizer Kevin Matthews, told local media this data is an indication that decriminalization does not increase the number of people breaking the law and that legalization wouldn’t either, but my point is that this initiative isn’t true decriminalization—and San Francisco’s isn’t either. So then, the question becomes: What will the city actually do about this resolution now that it’s been passed?

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Carlos Plazola, co-founder of Decriminalize Nature, a group that began in Oakland after successfully passing a resolution there to make the possession of natural psychedelics the lowest law enforcement priority, says it’s too early to say and that the resolution is undergoing a standard process of implementation. “If someone wants to understand the implications of our resolutions to decriminalize entheogens in a specific locale, there are fourteen cities that have far more data to study based on their much longer period with the resolutions in place. San Francisco is not the best city to study at this time as they’ve not even had a chance to implement the resolution,” he tells DoubleBlind.

Plazola outlined the process of implementation as follows: “Anytime that a council or board of supervisors passes any policy, particularly as it pertains to a law enforcement agency, there’s a process of integration into the procedures of the agency or department. It doesn’t happen overnight. There has to be a convening of the city’s attorneys representing the department, they then have to integrate the wishes of the supervisors into the police bulletin, then the police bulletin has to be circulated among all of the supervisors and line staff and then there has to be a training process around the police bulletin. Then, you implement; You go into the streets and you follow the recommendations of the police bulletin and training and then you have feedback loops. They look at: ‘Is everything going as it’s supposed to?’ This is a long process. It could take months to implement in any city or county.”

In my opinion, however, it’s important to take into account San Francisco’s current treatment of drug users when considering how much teeth this initiative may have. In a city struggling to find an effective approach to drug policy, San Francisco District Attorney Brooke Jenkins is attempting to tackle the overdose crisis with a rather hardline (and arguably unconstitutional) strategy.

In July of this year, Jenkins was appointed into office by Mayor London Breed following the heated recall election of former DA Chesa Boudin. During her sixteen-minute-long inaugural address at City Hall, the newly-appointed DA proclaimed that it’s imperative to “end the open-air drug markets and take back our streets.” Amid rounds of thunderous applause, Jenkins distinguished herself from her ousted predecessor: “Starting today, drug crime laws will be enforced in this city.”

San Francisco LEOs Clarify Position on Psychedelics

As of the present moment, there is no indication, that I’m aware of, that the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, Sheriff’s Office, or Police Department will abide by Resolution #220896 as-is, without any possession limits. After the Board of Supervisors unanimously passed the Resolution, the SFSO and SFPD provided clarification on their stance regarding the Resolution. The following quotes were obtained through private email correspondence with media representatives of the SFSO and SFPD:

“Psychedelics remain illegal under state and federal law,” wrote San Francisco Sheriff Office Director Tara Moriarty. “There may be circumstances during other enforcement events that the Sheriff’s Office may seize and/or seek to charge persons with crimes related to these drugs— when doing so will protect the safety of San Francisco visitors and residents.”

San Francisco Police Department Officer Kathryn Winters wrote, “The resolution from the Board of Supervisors urges law enforcement agencies to deprioritize enforcement of psychedelics, and does not legalize the use and sale of these substances. The SFPD currently does not prioritize the enforcement of psychedelics, but will continue to take law enforcement action, when appropriate.”

Separately, it’s important to note that San Francisco’s law enforcement community has not responded to questions regarding the establishment of training protocols for officers to utilize when interacting with people under the influence of psychedelics. Last year, Denver released the first-ever training for first responders in how to deal with people on psychedelics.

Decriminalize Nature San Francisco did not respond to questions regarding measures in place to prevent San Francisco’s DA, SFPD, and SFSO from spending city resources on the investigation, arrest, detention, incarceration, and/or prosecution of individuals who use DMT, psilocybin, mescaline, or iboga. James McConchie, co-founder of Decriminalize Nature San Francisco, said that they have been holding conversations with the SF Board of Supervisors for three years and that implementation takes time.

“The next steps related to the resolution to decriminalize entheogens in San Francisco revolve around our continued work with the Board of Supervisors and our law enforcement leadership,” McConchie wrote in an email to DoubleBlind. “As with most public policy it takes time. Time for the public to become educated, time to allow time for the policy priorities of the BOS to be integrated into the priorities of the police department, and of course patience as the different groups align their concerns and needs. This resolution was only passed 5 weeks ago, I expect continued work from our organization and city leadership to continue clarifying and creating the best model for safety, access, and equity that works for the great city of San Francisco.” McConchie also noted that “most decriminalized cities” have passed measures with similar language and policy.

Plazola says it’s important to consider the broader implications of this kind of reform too, pointing to cannabis as an example of how local reform has effects that are significantly more far-reaching than their legal teeth. He says they set a tone and impact of what’s enforced federally, even when laws remain the same. “The truth of the matter is that cannabis is not decriminalized or legalized at a federal level,” he tells DoubleBlind. “The only reason the feds are not attempting to seize properties the way they did all the way up to 2017 is because of the power balance shift. Not because of the law. It’s because the states have accumulated enough power to prevent the feds from doing seizures and raids and not making it in the feds’ interest to do anymore. To suggest that cannabis has achieved a different status relative to the federal law to psychedelics is a fallacy. It’s a power question and not a law question.” Decriminalize Nature, he says, targets cities, in part to impact federal action—something they can no longer do at the state level because power is too accumulated by corporate interests.

Read: Where Are Magic Mushrooms Legal?

…But What Does The District Attorney Say?

DA Brooke Jenkins has repeatedly made her opinion clear on the broader concept of drug decriminalization. Regarding her predecessor’s work at the DA’s office, Jenkins has maintained that Boudin’s choice to effectively decriminalize drug sales created an “explosion of what was already an ongoing issue in San Francisco.” Repeatedly rejecting the broader concept of decriminalization, Jenkins has asserted that she has a duty to “enforce all the laws” and “prosecute all crime” within the city.

In the process of reversing many of Boudin’s policies, DA Jenkins has begun threatening fentanyl suppliers with second-degree homicide charges if they can be causally linked to a fatal overdose. Although California is not one of the 20 states that have drug-induced homicide laws, the District Attorney’s Office asserts that the move is “in lockstep with other prosecutors” across the state. When the San Francisco Examiner asked DA Jenkins about this policy in late September, she was unable to provide evidence that drug-induced homicide charges are a cost-effective means of combating the overdose crisis.

In defiance of Jenkins’ various drug policies, San Francisco’s elected Public Defender Mano Raju has tweeted Jenkins’ “regressive” strategies come “straight out of the War on Drugs playbook.” This has contributed to what Raju has described as a “constitutional and human rights crisis right now going on in San Francisco.”

For his part, Plazola says that Jenkins’ drug policies don’t mean that Decriminalize Nature shouldn’t have worked to pass their resolution. “What’s happening in San Francisco and what’s happening with the District Attorney there is part of a national trend of progressive cities being attacked from the right. The fact that it’s effective is a reflection of a lot of fear in our society that ultimately will impact most marginalized communities of color. What’s happening in San Francisco is pretty ugly, but it’s way beyond plant medicine, it’s way beyond psychedelics. What we’re talking about is a shift to the right in a city that’s historically been a progressive bastion so it’s not just our resolution that’s in danger, it’s everything that’s progressive in San Francisco, and there’s no use in helping it by undermining good efforts.”

Plazola says that one of the reasons the deprioritization of plant medicines is important is because it raises awareness among communities that have been disproportionately targeted by the War on Drugs about these substances as tools for healing, in particular the healing of intergenerational trauma. When asked whether marginalized communities will be endangered by Resolution #220896, Plazola said that claims like mine are “very speculative and there’s no evidence of that happening yet in any of the cities where we’ve passed decriminalization, such as Detroit and Oakland.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

DA Jenkins’ New Drug Policy in San Francisco

Regarding the constitutional crisis that Raju mentioned, legal experts have questioned the constitutionality of the District Attorney’s new drug policy. In a nutshell, Jenkins’ new “five strikes policy” means that drug users in San Francisco will be referred to the Community Justice Center if they accumulate five or more citations for public drug use. Like other community courts, the CJC provides social services to accused individuals while they are placed under active monitoring.

In the SFDAO’s official press release, DA Jenkins asserted that this strategy “will save lives.” Though the policy is often framed as a compassionate means to provide health-oriented services, Jenkins’ critics have been quick to point out its major shortcomings.

One of DA Jenkins’ opponents in the upcoming November election, John Hamasaki, has described this new policy as an upgraded version of Nixon’s greatest failure: “the War on Drugs 2.0.” Drawing from his experience as a police commissioner and criminal defense attorney, Hamasaki has openly questioned whether DA Jenkins’ policy is truly compassionate, labeling it as “just another PR scam to fool the public.”

According to Hamasaki, the fatal flaw with DA Jenkins’ policy is that the drug treatment facilities utilized by the Community Justice Center are still underfunded despite Mayor London Breed’s recent expansion of treatment facilities. Mayor Breed has recently confirmed that at least one unspecified treatment center was “overwhelmed” and, as a result, was not able to treat “as many [people] as we had hoped.” Aware that these city-wide facilities are limited by funding, she acquiesced that “they can only serve so many people at a time.”

Because San Francisco’s drug treatment facilities are struggling to meet expectations, the Community Justice Court can order drug tests to monitor the drug usage of accused individuals. Hamasaki claims that defendants who test positive while their case is being overseen by the CJC would have their case sent to the Hall of Justice for criminal proceedings. As it stands, DA Jenkins’ drug policy effectively criminalizes the status of drug dependence.

Unfortunately, there are serious pitfalls with compulsory drug treatment programs utilized within the criminal justice system. The available peer-reviewed scientific literature indicates that there is insufficient evidence to claim that compulsory drug treatment is effective. Furthermore, many of these treatment programs are low quality, understaffed, underfunded, rife with corruption, often involve unpaid labor, and don’t significantly reduce odds of recidivism.

The American Public Health Association has raised ethical concerns regarding the notion of court-ordered drug treatment in simple cases of drug possession. Given that such people are effectively coerced into situations where they are not able to freely provide informed consent, court-ordered drug treatment programs violate currently-accepted bioethical principles. If that were not enough, the leading cause of death for individuals recently released from prison is drug overdose. Regardless of how you frame the data, it’s not a pretty picture.

Jenkins has repeatedly stood by her policy, insisting that five drug use citations are a “clear signal” that drug users are “in a crisis and need support.” However you want to slice it, the current legal landscape in San Francisco effectively criminalizes not just illicit drug use, but also the status of being physically dependent on the use of illicit drugs.

San Francisco Officials Target Open-Air Drug Use And Sales

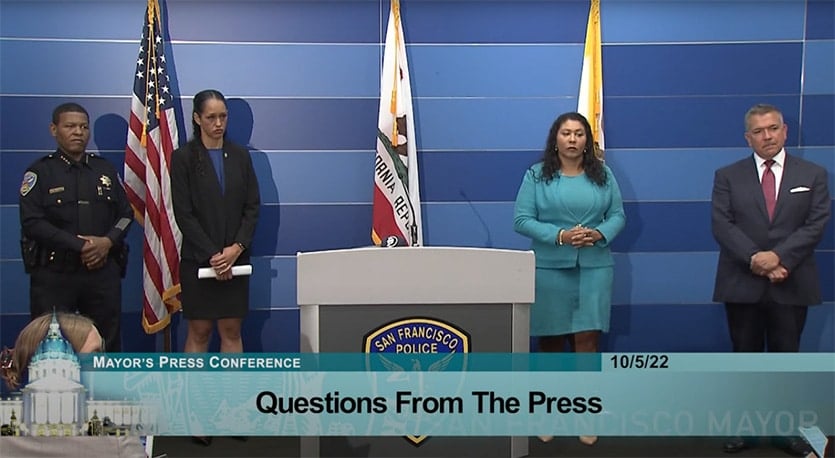

At a press conference held at the SFPD Headquarters on October 5, District Attorney Brooke Jenkins, Mayor London Breed, Supervisor Matt Dorsey, and Police Chief William Scott clarified the city’s position on the “open-air drug markets” within the streets of San Francisco, especially the Tenderloin District. Given that hundreds of San Franciscans are lost to the overdose crisis each year, Mayor Breed began the meeting by stressing her desire to “draw a firm line at behaviors that harm, injure, and cost neighborhoods peace of mind every day.”

Read: Decriminalization vs. Legalization: What’s The Difference?

Supervisor Dorsey distilled the essence of the entire hour-long meeting when he described the city’s policy as “a war on drug addicts.” Reminding the viewing audience of San Francisco’s grim overdose statistics, Dorsey said he “challenges” critics who are “committed to just complaining” about the city’s drug policy to “bring forward” their own solutions.

Though the word “psychedelics” didn’t come up at any time during the press conference, DA Jenkins once again criticized former DA Boudin’s choice to “effectively decriminalize” drug sales. The tense meeting focused mostly on fentanyl, but some of the heated rhetoric was also directed at general drug use.

Police Chief William Scott asserted that the city’s law enforcement officers are an essential element to “helping” substance-using individuals. As he put it, “our job is to take away all of the excuses.” If drug users aren’t willing to have a law enforcement officer direct them to a treatment facility, Chief Scott made it clear that this would be an opportunity for the criminal justice system to step in.

Scott described the SFPD’s approach to tackling the overdose epidemic at-length, repeatedly saying that even those suffering from substance use will not receive “a free pass.” He said that it wouldn’t be enough to just arrest street-level dealers, saying that his department “can’t just […] leave the people who are buying the drugs alone to do as they please and think that this is going to get better.” Pointing to the chronically-underfunded drug treatment programs within nearby jails and prisons, Scott asserted that “the criminal justice system has tools to get to that issue.”

Near the end of Wednesday’s press conference, Police Chief Scott said that his approach hasn’t been favorably received by “well-intended” drug policy advocates. Aware of the city’s widespread distrust of San Francisco’s law enforcement community, Scott called these concerns “excuses.”

Jenkins also announced that individuals charged with possessing “more than five grams” of any controlled substance would be barred from being admitted into the city’s rehabilitative courts. DA Jenkins described such individuals as undeserving of treatment. Disregarding the fact that drug users often possess non-miniscule amounts of drugs, DA Jenkins asserted that the Community Justice Center “should be reserved for those who actually need treatment.”

A Look at History

As seen in the past, alleged violations of drug laws have served as a primary tool for police to needlessly investigate and criminalize minority communities with impunity. When New York City decriminalized small amounts of cannabis in 1977, officers routinely abused loopholes to target Black, Latinx, and other minority communities.

Given that the police often break the law, it’s essential for these officers to be held accountable for their actions. Indeed, San Francisco’s police department has repeatedly been accused of engaging in racially-motivated drug arrests. San Francisco Police Chief William Scott has publicly defended one officer accused of violating California’s Racial Justice Act.

Additionally, DA Jenkins’ former colleagues have detailed how she spent her first weeks in office firing and demoting attorneys at the SFDAO, especially those tasked with investigating police officer misconduct (e.g. excessive force). The position of managing attorney of the Internal Affairs Bureau was left vacant for two weeks. Regardless of Jenkins’ motives, her actions temporarily limited the ability of the SFDAO to fully investigate police misconduct.

Read: Biden Administration Prepares for Legalization of MDMA and Psilocybin Within Two Years

The Criminalization of Substance Use is Cruel…and Unconstitutional

Sixty-two years ago, on a chilly February night in Los Angeles, two plainclothes LAPD officers pulled over a vehicle occupied by four Black people. In events that followed, the officers noticed Lawrence Robinson, a twenty-five-year-old Army veteran in the backseat, was sweating from withdrawals. They examined his arms—which had scars on them from injections—placed him in handcuffs and subsequently held him without bail.

In June of 1960, Robinson was convicted by a jury of his peers for violating a section of California’s Health and Safety Code which explicitly prohibited the status of being “addicted to the use of narcotics.” Jurors were provided with a magnifying glass to form their own opinion as to whether Robinson’s scars were caused by intravenous drug use.

The trial judge advised the jury that the law “subjects the offender to arrest at any time before he reforms.” Simply put, the judge reminded the jury that they had the ability to convict Robinson “so long as it found him an addict.” Although these jurors were simply performing their “civil duty,” they unknowingly sealed Lawrence Robinson’s fate.

Nearly two years after his trial, oral arguments for Robinson v. California were held in the United States Supreme Court. Representing Robinson, Samuel Carter McMorris argued that Section 11721 of California’s Health and Safety Code was unconstitutional—that the criminalization of substance use violated the right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment.

Robinson was truly blessed to have an attorney who had already successfully argued a case before the Supreme Court. McMorris was equally fortunate in that the Court appreciated the merits of his arguments even though he was audibly nervous.

Within the recording of the oral arguments, you can hear Justice Harlan ask McMorris whether or not he was aware of drug users who underwent “a series of prosecutions for the same addiction.” Speaking plainly, McMorris replied that he saw it “every day.” He remarked that he was aware of policemen who were arresting people simply based upon “some evidence of continued use.” Over the course of the oral arguments, the Court openly questioned whether the California law violated the Fifth Amendment given that California’s substance users were, as McMorris asserted, “inherently” subjected to multiple prosecutions.

Two months after oral arguments were held, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Lawrence Robinson. In a decision authored by Justice Potter Stewart, six justices agreed that laws criminalizing the “disease” of addiction “would doubtless be universally thought to be an infliction of cruel and unusual punishment.”

Justice William Douglas added in a concurring opinion that the unconstitutional law “permitted sick people to be punished for being sick.” Put in plain language, Justice Douglas made it clear that the objective of the law was “not to cure, but to penalize.” Emphasizing the perspective of the medical community, Justice Douglas remarked that California had ignored the research indicating that criminalizing substance use disrupts “possible treatment and rehabilitation [and] therefore should be abolished.”

Though portions of the Robinson decision continue to be quoted by advocates for decriminalization, this supposedly-progressive ruling made it clear that states still retain the legal ability to force substance users into “compulsory treatment involving quarantine, confinement, or sequestration” so as to protect the “general health or welfare of its inhabitants.”

Although Lawrence Robinson’s case was a landmark victory for progressive drug policies, there’s a disheartening end to his story. Unbeknownst to McMorris, the client he successfully represented passed away in an alleyway in August of 1961 from a possible overdose. Even though Robinson had already been laid to rest, McMorris told the Supreme Court that Robinson was “still on probation” at the time of oral arguments. Robinson’s death should compel legislators, judges, and government officials to pause just enough to realize how little progress our nation has made regarding drug reform. Had the state and federal government funded sufficient harm reduction services, safe use sites, safe supply facilities, and treatment programs, Lawrence might still be with us. More than sixty years have lapsed since his passing, yet his legacy lives on.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In light of the current drug policy in San Francisco, what can be learned from Lawrence Robinson’s story? Although five decades have passed since Nixon’s failed War on Drugs officially began, our nation’s cities have still not enacted drug policies that sufficiently protect public welfare while respecting the rights to privacy and autonomy.

In the meantime, San Francisco’s still debating whether implementing safe consumption sites are an appropriate means to prevent overdose deaths. Given the evidence that such facilities effectively prevent lethal drug overdoses, various San Fran officials have publicly supported the implementation of safe-use sites as well as safe supply centers.

From my perspective, ending the overdose epidemic would require massive increases in funding for safe use sites, safe supply centers, treatment facilities, public housing, meaningful employment opportunities, public education campaigns, expungement of criminal records related to drug violations, and other non-punitive approaches that are based upon harm reduction principles. Just as well, the decriminalization of the personal use of controlled substances would put an end to the irrational choice to incarcerate our way out of a public health issue.

To be fair, Decriminalize Nature has supported broader drug and criminal justice reform, such as a failed initiative in Michigan in partnership with Students for Sensible Drug Policy and initiatives in Massachusetts that included the decriminalization of all drugs, but they continue to focus on the deprioritization of natural psychedelics. I believe if there’s a lesson to be learned from the decriminalization movement in San Francisco, it’s that resolutions that encourage law enforcement agencies not to criminalize the possession of psychedelics are not enough. These resolutions create a narrow legal carve-out for a class of drugs used by the minority while disregarding the urgent needs of fellow drug users.

Though the Resolution states that various psychedelics are “reported to be helpful” in the treatment of drug addiction, the document doesn’t acknowledge that many of these scientific findings are preliminary in nature and require further investigation. Well aware of the public’s rising interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, the American Psychiatric Association released a concise statement three months ago which clarified the organization’s stance on the nascent field of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

With the knowledge that people may look to the APA for advice regarding psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, the organization urged caution when it advised that the current scientific evidence regarding the investigational form of therapy is too “inadequate” for them to endorse for “any psychiatric disorder except within the context of approved investigational studies.” Simply put, the APA believes that it would be irresponsible to support the adoption of clinical treatments based on “ballot initiatives or popular opinion.”

By way of contrast, the first page of Resolution #220896 claims that “the use of Entheogenic Plants have been shown to be beneficial” in “addressing” a handful of serious medical conditions. One of the enumerated medical conditions which can supposedly be “addressed” with the use of “Entheogenic Plants” is diabetes. With an estimated 5.9 percent of San Franciscans having diabetes, as of 2016, the San Francisco chapter of Decriminalize Nature was unable to reference peer-reviewed clinical literature which supported the claim. In response to allegations that the Resolution misinforms the city’s diabetics, Decrim SF said that they “certainly don’t want to lead people with diabetes astray” and agreed that “we need a lot more research” to verify the claims within the Resolution.

Indeed, caution is certainly warranted given that these non-specific amplifiers of consciousness can also engender utterly terrifying experiences which can be emotionally destabilizing. Such experiences can become exacerbated when there’s no psychological support before, during, and after psychedelics are self-administered. Additionally, given that current psychedelic clinical trials screen out people with comorbid mental health conditions, there’s effectively zero research on the effects of psychedelics in populations with complex mental health issues, especially those who are unhoused. In other words, it will take more than consciousness-altering drugs to overcome a city’s overdose crisis.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DoubleBlind

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.