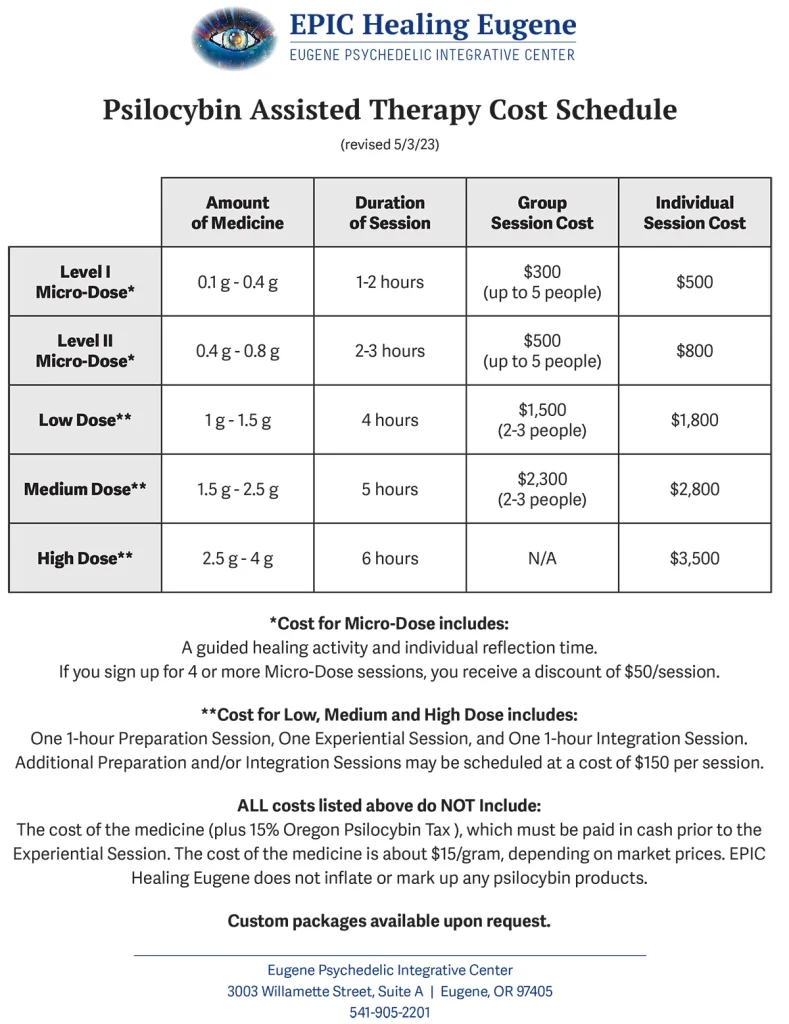

Oregon has officially licensed the first-ever regulated psilocybin service centers in the United States, and legal journeys are set to take place this summer. A guided trip with four grams of mushrooms will cost $3,500 per session. A two-and-a-half gram session will cost $2800.

A reported 80 people signed up on a waiting list to access psilocybin with the first green-lit facility, Epic Healing Eugene, where they will undergo a supervised magic mushroom journey. “This is the first step, and we will soon work to create more access for people to this life-changing therapy through scholarships and creating ways for people to sponsor services for other people,” owner Cathy Jonas said in a press release.

“Witnessing clients engage in their deep interpersonal journeys within themselves, as well as my own personal experience working with healing psychedelics, has enabled me to work through the challenges of opening up a service center in Oregon.”

The clinical social worker underwent a 300-hour psychedelic-assisted therapy training program and her company will also offer tailored preparation and integration sessions. “The majority of the people that are coming have PTSD and trauma,” she told KLCC. “Probably a good third are very depressed.”

The former campaign manager of the ballot initiative that saw the psychedelic mushroom measure pass, Sam Chapman, now executive director of the Healing Advocacy Fund, has said there could be a dozen service centers open by the end of the year after facilitators and growers were licensed earlier this year.

But the announcement of the first facility’s prices has led to criticism that the therapy will be “totally inaccessible” to those on lower incomes. Unlike Colorado, which passed a similar psilocybin regulation measure last year, Oregon did not decriminalize psychedelics. Well, not entirely, at least. In 2020, Oregonians decriminalized the personal possession of small amounts of illicit substances via ballot Measure 110. Oregonians can legally possess under 12 grams of psilocybin mushrooms. However, gifting, exchanging, or selling psilocybin mushrooms is not legal outside of the service center framework. Therefore, the only way to legally acquire the mushrooms is through a licensed service center.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

“Officials claimed that Measure 109 did not give the agency authority to create regulations that directly addressed the accessibility issue,” Mason Marks, former chair of the Licensing Subcommittee, told DoubleBlind. “That’s somewhat debatable. But at least some of the fault lies with the drafters of the ballot initiative, who decided not to make affordability a priority. By comparison, those who drafted Colorado’s Proposition 122 made the affordability of services a focus of Colorado’s advisory board.”

Jonas said that along with the $12,000 training and certification fees for her alone, she must pay a $10,000 annual fee and $60,000 on insurance and security. Service centers cannot write off costs like wages and rent on their federal taxes, because psilocybin is federally illegal. Psilocybin businesses are excluded from tax benefits offered to other businesses—large and small alike—due to US tax code 280E. The code prohibits basic deductions for those that engage with Schedule I and Schedule II controlled substances. Service centers are expected to generally compensate for that by having prices 30 percent higher than they would be otherwise.

“High prices may be unavoidable when one sets up such a complex regulatory system for a substance that remains federally illegal,” added Marks. But, he claimed, “I don’t think most Oregonians envisioned something this expensive, and there were choices made during the rulemaking process that over-complicated things, and unnecessarily increased costs.”

He also cast doubt on whether insurance companies would soon be able to cover patient outlays in Oregon. Marks, a legal scholar at Harvard Law School’s Petrie-Flom Center, further claimed that prices could potentially continue to increase if a bill passes the state legislature house this week requiring service centers to provide intimate personal data to a state database.

A series of other drug policy campaigners and experts also criticized the prices, which are expected to be similar at many other service centers. “This is absurdly expensive for legal psychedelic access; totally inaccessible to key populations on lower incomes (who could—if you buy the trauma therapy arguments—benefit the most),” tweeted Steve Rolles, senior policy analyst at Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

The Psilocybin Oregon campaign group tweeted: “At $3,500 a session it is for rich people only. Please don’t copy the ‘paywall prohibition’ model we have in OR, instead bring full decriminalization to your community and help everyone heal!”

$3,500 a session!

— Psilocybin Oregon (@PsilocybinOR) May 7, 2023

Please don’t copy the “paywall prohibition” model we have in Oregon.

It is wrong and will not work.

Instead bring full decriminalization to your community and help everyone heal! https://t.co/KxB4KugNOz

Tensions between the legacy market—those operating underground prior to Measure 109—and the new service center system have also been a topic of conversation. The maximum legal trip is five grams, which some observers claimed is “hilariously low,” and could dissuade psychonauts from legal access even if prices plummeted. In December 2022, Portland Police raided and closed Shroom House, an unlicensed psilocybin mushroom dispensary that operated openly downtown for several months.

“There are people and organizations openly facilitating psilocybin trips outside of the state-run system in Oregon,” Vince Sliwoski, a lawyer at Harris Bricken Sliwoski LLP, told Willamette Week. “You don’t have to look that hard to find them. There’s going to be a big underground economy for this stuff.”

James Hin, a former organizational manager, has opened a psychedelic church in Eugene named Psilo Temple, and dozens reportedly attend his “Wisdom Wednesday” services, where psilocybin mushrooms are consumed as devotees’ sacrament. “I’ll defend these protections all day,” Hin told Willamette Week. “I’m not some hippie in a van … I feel like I was sent here from the universe to do this.”

Interested in having a psychedelic experience, but don't know where to start? Get our definitive guide on trusted legal retreat centers, clinical trials, therapists, and more.

We started DoubleBlind two years ago at a time when even the largest magazines and media companies were cutting staff and going out of business. At the time we made a commitment: we will never have a paywall, we will never rely on advertisers we don’t believe in to fund our reporting, and we will always be accessible via email and social media to support people for free on their journeys with plant medicines.

To help us do this, if you feel called and can afford it, we ask you to consider becoming a monthly member and supporting our work. In exchange, you'll receive a subscription to our print magazine, monthly calls with leading psychedelic experts, access to our psychedelic community, and much more.