This interview is a part of DoubleBlind’s Medicine Music series, in partnership with PORTAL, a campaign to destigmatize the responsible use of psychedelics. For video interviews with musicians about their relationship to plant medicines, check out DoubleBlind’s YouTube.

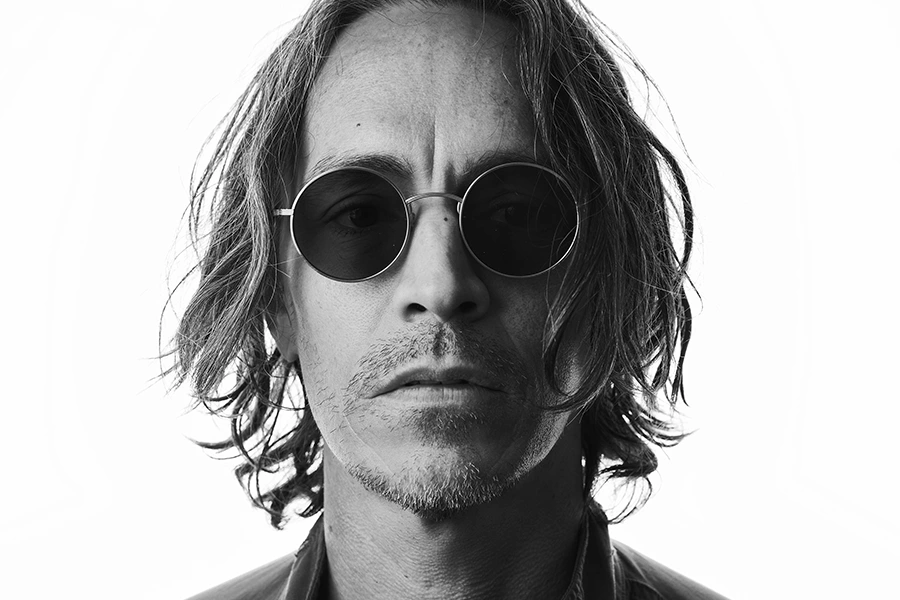

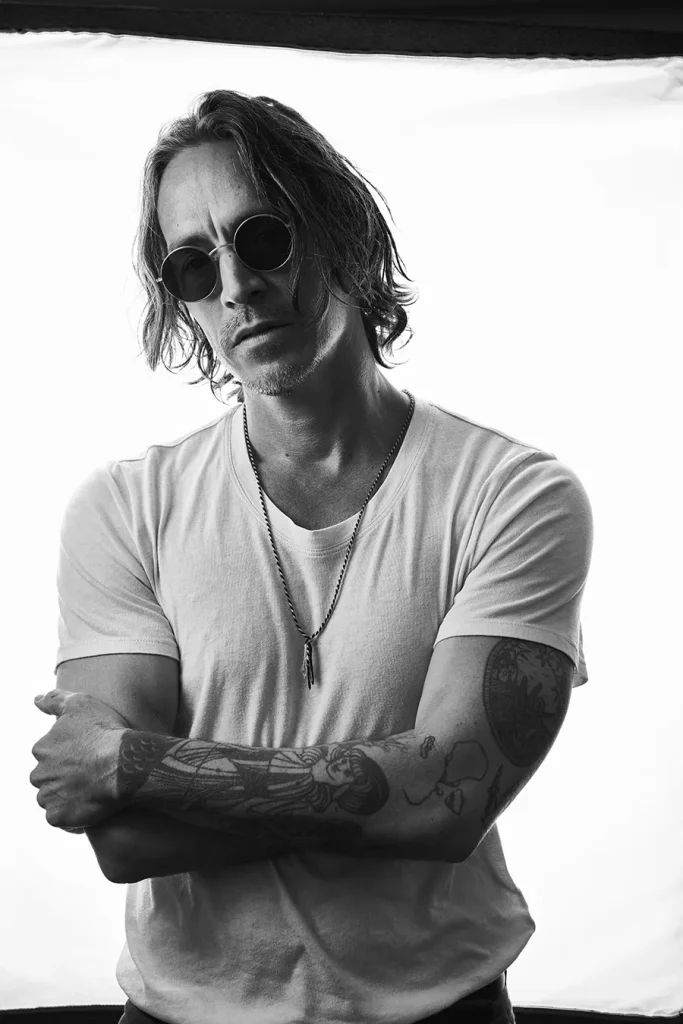

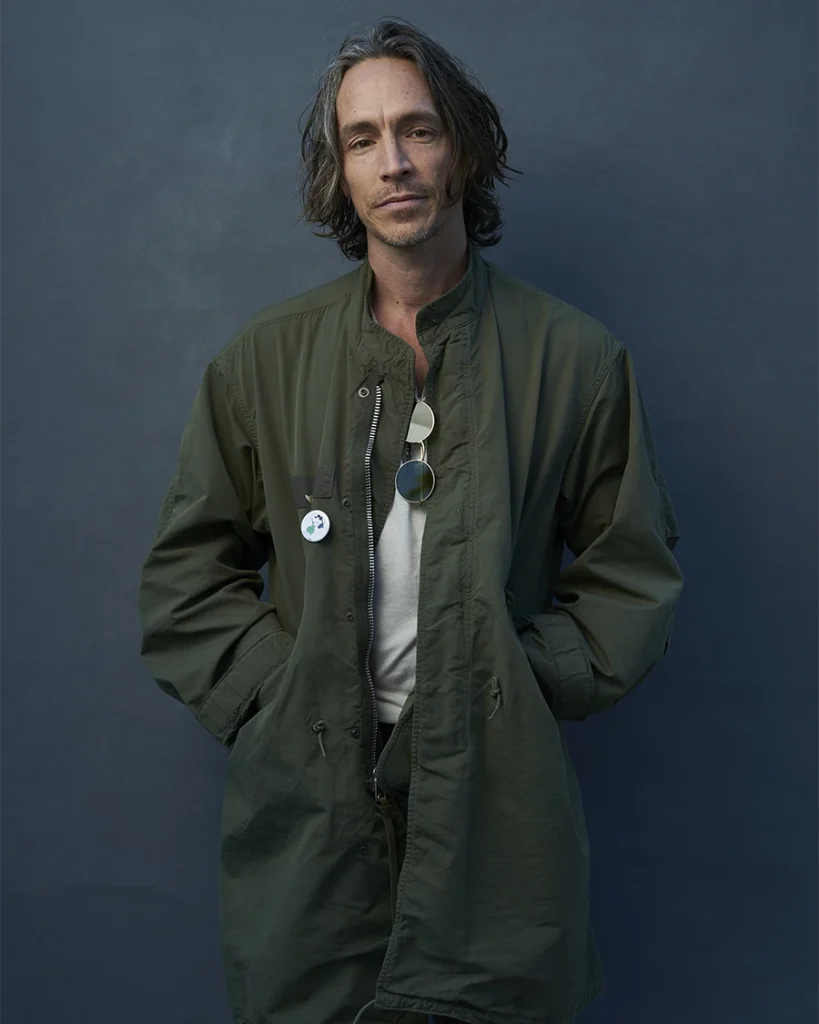

Brandon Boyd may be the most well-adjusted rock star in Los Angeles. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the bottom-heavy crunch of nü-metal and rap-rock was reverberating across the nation, but Boyd became famous instead for his holistic spin on alt-rock as the frontman as the lead singer for Incubus. Boyd and his friends Mike Einziger and José Pasillas founded the band when they were high-school classmates in 1991. Within a decade they were gaining international acclaim for their heady guitar riffs, turntable-scratching grooves, and spiritually tuned-in lyrics of hits like “Stellar,” “Pardon Me,” and “Wish You Were Here.” They’ve been at it ever since, cultivating a devoted fanbase with a string of well-received albums and a regular schedule of tour dates.

Born and raised in the San Fernando Valley, Boyd grew up in close proximity to the VIP excesses and drug-fueled abandon of 1990s Los Angeles. Heroin and crack were easy to come by in those days, but Boyd played it safe, sticking to the psychedelic staples of cannabis, psilocybin, and LSD as he nurtured his artistic talents through regular band practices and dream-time musings. The 47-year-old singer and songwriter tells DoubleBlind he’s always relied on his “observer” instincts to assess his surroundings and think carefully about what he puts in his body. “I suppose I am sensitive to particular kinds of energies,” he says, “and there are some that I’m just not really interested in.”

READ: The Best Psychedelic Albums Through the Ages

With a mind well practiced in out-of-body experiences and a singing style that’s matured through 30-plus years of live performances and recent surgery, Boyd experiences the world a little differently than everyone else. In his recent sit-down interview with DoubleBlind, Boyd’s discusses his ideas on God, spiritual practices, and his experiences with various plant medicines and other substances. He’s a deep thinker and big dreamer, but he also has practical advice for anyone looking to dive into the world of psychedelics via an overflowing cup of Ayahuasca or medically prescribed ketamine.

“I think one of the most important things that we could teach to people who are coming online with these things right now is ‘set and setting.’ Make sure you check your intentions as you’re coming into it, and make sure you’re in a place where you’re safe,” he says. “Don’t take acid and go to school, that’s stupid. And it’s a waste of a high. Unless your school is in the forest and Gandalf is your teacher—then maybe take acid and go to school.”

The two carry on a wide-ranging discussion full of remarkable insights, generous reflections, and surprising tales from his life as a musician. We put together a condensed version of the interview below, or you can watch the whole hour-long video on our YouTube channel.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

*This interview has been edited for clarity

DoubleBlind: When did you have your first spiritual awakening?

Brandon Boyd: I actually don’t know specifically what the first time was. I do remember being a little kid. My family has had its ups and downs over the years, but one thing we did right was sit down for dinner together almost every night when I was a kid around this beautiful, long wooden table. I remember sitting at one side of the table, and almost every night from the time I was, like, I want to say, maybe seven or eight years old, I would have what could be described as continuous out-of-body experiences. I would be at dinner with my family, and I remember feeling I could play with it. Everything would get further away and then I could pull it back in. At one point, I remember I started getting really good at it, and I could look down at the top of my head.

Maybe I was just tired. Maybe my mom’s broccoli had some kind of, she sprinkled some, like, extra special stuff in it—who knows. I remember having that experience, and then, the older I got, the more I would sort of look at it objectively, and to the best of my ability, be like, “What was that?” And then as a young teenager into my teenage years, I would play with that. I would play with it during dream time, as well. I’ve always had a very healthy dream time. A lot of music comes from there.

Journaling?

And journaling. But the advent of recording devices, even the early rudimentary ones, well for me growing up in the late ‘70s and the ‘80s, so like tape recorders. I have just tons and tons and tons of ‘em that I go back to. I was humming melodies that I would pull out of that kind of fuzzy, in-between area, between dream time and waking. I learned to kind of hover there, and it was sort of a quasi-lucid space. I don’t know if you could call that spiritual, but I suppose however you individually decide to interpret that could be considered part of a spiritual process. Does that make sense?

READ: The Best Psychedelic Songs of All Time

It does. And everybody has a different interpretation—that’s what’s beautiful about the world, right? I actually have talked to a lot of people who have had those kinds of experiences, of the lens, or the view. The higher power, maybe God view. I’ve had that too.

That’s what’s so wonderful about coming into a meditation space. There’s the experience and then there’s the observer. You’re in a meditative state and have no thought, but then there’s a part of you that’s objectively understanding and realizing that you’re not thinking.

What was your first plant medicine?

Cannabis.

Same. Pretty common.

Especially growing up here in Southern California.

And then what?

Then it was psilocybin.

Same. Was it a gradual thing for you?

Relatively speaking. I was in the D.A.R.E. generation and the Just Say No thing. The Regan stuff. I think I was in fourth grade, maybe fifth grade, and they picked me to act out some of the skits. The D.A.R.E. people would come to the school, and be like, “You and you and you—you’re going to do this role. You’re going to be the drug dealer and you’re going to be the kid that says, ‘No, I’m not going to do that!’ And I remember just [saying], like, “Cool, great!” So, I had a very distinct, sort of propagandized impression of drugs writ large.

But, when I was 15—it was the same year we started the band—I tried cannabis. And I got really lucky for my first experience. I was with my older brother and my girlfriend at the time, and my older brother came into this strain of ganja called Alaskan Thunder Fuck—have you ever heard of it? It was like the strongest [strain] that existed at that point.

I don’t know why it got that name. I don’t know if it actually came from Alaska. But my brother was hesitant to, like, get me stoned with him. But then the girl that I was dating was a couple of years older than me, and she was like, “We’re all here together, it’ll be fine.” I had a full-blown psychedelic experience the very first time. It agreed with me in a lot of ways. And I was slow to adopt it, but then I got super into it through high school. We had started our band, and it was a really interesting, sort of accompaniment to writing music with my friends.

I don’t remember how old I was the first time I took psilocybin, though. It was maybe a year later—a year and a half. We didn’t know about microdosing back then.

Nobody did.

It was like, ‘How much do you eat? I don’t know. Eat the whole bag!’ So, it became kind of common practice to eat an eighth of an ounce.

Did you get into any hard drugs when you were younger?

No. There was a very, very distinct demarcation line between what people were taking. Growing up in San Fernando Valley, there was no shortage of access to literally any drug you could think of. I had friends who got lost with crack, I had friends who got lost on PCP, and different methamphetamines. Once again, in that observing spirit—like we were talking about earlier—if I have any talent at all, it’s a talent for reading the room. I would watch what happened when people would smoke cannabis or take mushrooms or smoke crack or do a line of blow, or if they sprinkled angel dust onto their pot in their pipe. And so I knew exactly what to stay away from, and I had some close friends who got really lost, and I had quite a few friends die as a result of interactions with bad substances. What I consider bad substances. Still to this day, I’ve never tried cocaine. I’ve never smoked crack. I have no interest.

Good for you.

They carry with them very particular energies, and so I suppose I am sensitive to particular kinds of energies, and there are some that I’m just not really interested in.

Besides meditation, what are your spiritual practices?

Besides a daily meditation—it’s very simple, it’s 20 minutes every day—I got turned onto tea. Drinking tea. And not like, a Lipton’s in a bag doing this [motions dipping a teabag in a cup] and hugging the warm mug and looking out the window and going, ‘Hmmm,’ on a foggy day. Not like that. Though that is probably a wonderful spiritual practice for some people.

No, my former partner, she became fully enamored with Cha Dao, the way of tea. There is a tea teacher who came from Taiwan into Venice, where we lived, and he started doing courses. And so I went a couple of times just because it sounded intriguing, and I would just drink tea in silence with these new friends. And it was delicious. That was like the entry point. I was like, “Whoa, I’ve never had tea like this before.” It’s like aged, handpicked, hand-cured tea from China. It’s very specific. I’ve been doing it now for over a decade. I bring it on tour with me. I’m home every afternoon, I sit down and I drink tea. It’s a lovely accompaniment to meditation.

You could also not necessarily call it a spiritual practice. I’m at a point in my life—and I have been for sometime—where I am not putting as much stress on what some people might call “a spiritual practice.” I’ve come to a point where the whole thing is a spiritual practice. Everything: driving, shaving, shitting, eating, making love, fighting, gardening, being on tour. All of it is part of this huge process that we’re in the midst of not only experiencing but attempting to understand. So, how is that not a spiritual practice?

It’s reaping the lessons and the awareness from every single experience.

Yeah. And there’s something miraculous that happens, for me at least. Tell me what you think about this, but as a result of that little tweak in the perceptual framework, everything [becomes] a little bit more miraculous. Once you start to see everything through that lens, it’s like, the greens are greener. You’re like, “Whoa! What an amazing—wow!” You just start noticing things differently. And it’s a lot more fun, I have to say.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Have you noticed your vocal range change a lot over the years?

Yeah, yeah. When we first started—we started the band when we were 15—I did not know how to sing. I just knew how to project my voice. I could sort of bark, loudly. And it was necessary because, you know, we were just in a garage or in a living room or something, and the drums were always the loudest thing. The bass and the guitar were trying to turn up to try and match the volume of the acoustic drums. And then we started micing the drums, so they were turning up even more. And this is before we had, like, in-ears where we could hear what we were doing precisely.

Even when you’re mic’d, it’s still hard to project over those things. So learning how to sing came after actually being in a band. It was many years in that I actually kinda figured out, “Oh, it’s more interesting, it’s more challenging but it’s more interesting, and maybe it lasts longer if I actually create a melody.”

Do you have any rituals before or after a performance?

I just have something to eat, and then I usually go to bed. Which is an amazing ritual.

Yes, it is. I haven’t learned it yet.

[laughs] Life is still too exciting.

It is! There are still things I’m reaching for. You can rest now—you’ve given enough of your time and energy.

Yeah. Like I said, [performing is] a big energetic ask. And [you] put out a lot, but then you’re receiving a lot too. So after we do a concert, I sleep like a baby. You’ve given everything.

Have you raised a baby?

No.

They don’t sleep like that.

[laughs] I know, where does that saying come from? [laughs] You sleep like a rock star, is that maybe a thing? But they don’t usually sleep either, so…

Have you been to the jungle yet to drink Ayahuasca?

You mean literally the jungle?

Yes.

Okay, no, I haven’t. I’ve been to the jungles of Topanga where I had my first Ayahuasca experience.

Peru, Brazil. You never felt called to go?

I’ve definitely felt called. I approached Ayahuasca with a sort of relative caution because I had this sense that it was not like other plant medicines. I’ve had one experience. It was supposed to be a double-nighter, and after the first night, I went home to take a nap, and I slept for 20 hours.

READ: What Made María Sabina Unique

They let you leave?

Yeah, because I was right down the street. But it was here in the Valley. But it was a Brazilian ayahuasca shaman who came to visit the person who was hosting that night. He happened to be a famous Brazilian jazz musician too, so he was a musician-slash-ayahuasquero.

Really? They just let you go home?

Yeah.

Usually they don’t let you do that.

Really?

Really! It’s a container. It’s like, “Here’s the space we’re creating together—we’re having this experience.” People aren’t supposed to leave.

Interesting. So there were some rule breakers there. I was the rule breaker. I don’t know how other ayahuasca experiences go, but when we lined up to take the medicine, he was pouring individual cups and then handing them over. Once again, in that observational space, I was really clocking the room. I was looking around, and I was watching how he would pour. He would look at the people, smile, and then pour. He was pouring less for some people and more for others. By the time I got to him, I just smiled at him, and he looked at me, he looked me up and down, and he kept eye contact and he poured. And the cup was just bubbling over. He held eye contact and I was like, [surprised face], ‘Wow. What does this mean? I think I’m in for it!’ [laughs]

So you had a full cup.

Yes.

Were you like, “Bro, can you bring that down a little bit?”

No, I went into the experience with full surrender. I was ready to fully, fully surrender to it. What was your first experience like?

Not like that.

Where were you? Were you in the jungle?

Oh, no, I was in the Hollywood Hills, overlooking the whole city, looking at the clouds turn into skulls. I never wanted to be here for it. I wanted it to be in the jungle and it just didn’t happen. But I was in a place, emotionally… I was suffering so much that I was willing to do anything to not feel that way anymore. So I just said yes. And then I mostly got invited in for the music, because—as you may have found out—music is a big foundational piece of this medicine. The songs that have come through Ayahuasca to the people are incredibly beautiful. The translation is gorgeous, and so I fell in love with the music.

I fell in love with it too. I was blown away. They were performing it live in the room, and there were multiple singers who were doing these crazy harmonies during the experience. I had a hilarious experience before it went into sort of a deep, deep dive. There’s a window of time where you’re just sort of high, you’re just really high, but you’re still kind of there and you’re like, “Wow, I’m really high right now. Maybe I’ve never been this high.”

There were songbooks that they were passing around, but they were all in Portuguese. All of the music they were singing was in Portuguese, and it was beautiful. It was deeply intricate and psychedelic, all acoustic instruments, acoustic voices, the whole thing. And at one point, about an hour into the experience, I spoke Portuguese. I’m not exaggerating. I was reading it and I was like, ‘This is so wild’—once again, in that observer state—’why do I understand the lyrics right now?’ I was singing like I already knew the songs. I stopped and I just laughed for probably 20 minutes straight. ‘This is so cool! I speak Portuguese!’ And then it went away.

It was a whole night. I’ve been unfolding it and trying to make sense of it ever since—and this was probably 12 years ago.

Wow. You’ve never felt called to go back?

I’ve felt called a lot of times to go back. I’ve always erred on the side of respect [with these plant medicines], and with a relative caution. I’ve never had a bad experience, and there was a period of time in my 20s when I was taking mushrooms and LSD a lot.

Same time?

No, no, no, no, no. It would be one or the other. Lots and lots of experiences during that period of time. Formative experiences, you could say. I learned in those periods of time that I was psychologically and spiritually robust. I would take some of the same compounds with friends, and I would have a completely different experience, you know what I mean?

You also learn that there are some people who shouldn’t take these compounds. But I’ve wanted to approach them with, number one, a base layer of respect. Because they can turn on you just as easily as they can give you access to the unified field, or God, or whatever you want to call it. If you approach them with a little bit too much, I don’t know what the right term is—a little too self-assured—something happens. They can flip on you. And who’s to say whether or not that’s a good thing or a bad thing. Sometimes we need to be kind of straightened out.

What are your thoughts on ketamine?

My one experience with it was very interesting.

Did you enjoy it?

I did. I don’t think I had what you could consider a psychedelic experience. It was medically prescribed and I was in a controlled environment, and I just felt sort of lovely for about two hours. So I don’t have any problem with it.

Nice! Do you have any views or opinions on the clinical use of ketamine and all these psychedelic drugs that are now being prescribed?

I can’t speak much to ketamine, but I think that the idea of psychedelic-assisted therapy is something that’s potentially profound. Something like Ayahuasca wouldn’t normally occur here, just because of certain botanical limitations in Southern California. But we see it here, and it’s become massively popular here, of all places. Los Angeles. Why Los Angeles?

Well, because it’s a spiritual mecca.

That’s true, but it’s also culturally so fucked up here.

That’s why we need it.

That’s my point. It’s interesting how these compounds show up almost as avatars, as to where they’re needed the most. And Los Angeles needs spiritual help.

READ: Trip Tunes: A Conversation with Producer Jon Hopkins About Making Music for Ketamine

And everybody loves prescriptions. So why not?

But yeah, as far as psychedelic-assisted therapy, I think under the right circumstances it can be profound. Incubus has a nonprofit called the Make Yourself Foundation. We started it in 2003 but very recently, one of the most recent grants we did was to Heroic Hearts, who are working with MAPS [the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies], doing psychedelic-assisted therapy with veterans. Their success rate is… it’s amazing. For PTSD, trauma, and anxiety around terminal illness, these things are potentially incredible.

Yeah, I agree. I think when it’s used in that way, to treat specific symptoms, it’s a beautiful thing. There are a lot of people who also just love trying new things and doing things ritually because they enjoy the feeling, you know? So that’s why I ask the question. What are your thoughts on the politics, or like, the future I guess of where this could be going? Could you imagine getting a prescription for ayahuasca? I don’t know where it’s moving, but I think this is a great time to pay attention.

Absolutely.

To just notice how people around you perhaps are changing. What are they doing in their lives? What are they doing to overcome their own personal trauma? Is it really helping or is it just another thing that people are getting kind of hooked into—because it’s cool, because it’s trending, because it’s accessible?

This is where I would recommend relative caution, or a base layer of respect for the potential that these compounds carry with them. Like we’ve been saying, there’s the potential for [psychedelic medicines] to break you open in ways that you never have even conceived of. It has the potential to do so many incredible things for your mental health, for long periods of time, in one experience. I would argue that most people have positive experiences with these compounds.

[But] there are very specific sub-groups of people who should not mess with these compounds. They can tip you off in directions that are, at the very least, unpredictable. I’m sure growing up around these things, you’ve seen enough people who had experiences that tipped them off in the wrong direction. It’s like, educate yourself.

I think one of the most important things that we could teach to people who are coming online with these things right now is ‘set and setting.’ Make sure you check your intentions as you’re coming into it, and make sure you’re in a place where you’re safe. Have a backup plan. Just be smart about it. Don’t take acid and go to school, that’s stupid. And it’s a waste of a high. Unless your school is in the forest and Gandalf is your teacher—then maybe take acid and go to school. Wouldn’t that be cool.

What are you looking forward to most on this tour?

We’re playing with a new musician right now. We’re playing with a girl named Nicole Row, she’s playing bass in the band. We just did our first three shows with her this past week, and she’s doing an amazing job. She showed up and really did her homework. She knew some of our songs better than we did. It’s like… “‘Are you sure how that goes?’ ‘Yeah!’ ‘I don’t think so.’” And she was right. It’s going to be really fun continuing to play with her and have that fresh energy.

This feels like an aside, but I’m going to get to the point of it as quickly as I can. I broke my nose twice growing up, for stupid reasons. Once was onstage at the Whiskey a Go Go. I caught the headstock of a bass guitar in my face, and it broke this part of my nose and it knocked me out onstage. I woke up to the stage rumbling and our old bass player, who unfortunately had knocked me [out], was kicking me, going, “Get up! Get up!” And so I got up real dizzy, bleeding out of my face. I finished the set. I didn’t go to the emergency room or anything. I broke it there. And then when I was in 7th grade, my nose was broken by an egg that was thrown at my face.

Boiled?

I don’t know. There was just blood everywhere. Don’t break your nose, it sucks! Anyway, so I grew up with a severely deviated septum, and I learned how to sing on one nostril. I could never breathe out of the other side, there was no airflow.

As we age, as you know, our ears and our noses never stop growing. So if your septum is deviated, it continues to deviate and deviate and deviate. Breathing gets harder and harder. I got to a point where I sang on it as long as I could, because I was not looking forward to the surgery that needs to be done to fix it. I went through almost seven years, I felt like I was losing my voice because it was harder and harder to just [inhales]. I was becoming a mouth-breather, which isn’t a good look for anybody.

So December of 2019, I had my septum repaired. And somebody pulled a switch somewhere and turned off the whole world for two years while I was recovering. There is a lot that went wrong during the covid-era, that’s a whole other conversation. But to have two years to allow for the inside of my face to repair and then to relearn how to sing, because that’s what has to happen… I had this weird opportunity, 30 years into my career, to learn how to sing over again. So, what I’m looking forward to the most on this tour—and what I’ve been experiencing over this first handful of shows—is I can breathe. I’m finding places in my voice that probably would’ve been there had I not grown up with a twice-broken nose. It’s really exciting to be feeling that. Especially now, almost 33 years into being in a band.

I’m so happy for you. It’s like a new freedom.

Really. Breathing is awesome.

We forget to breathe. We forget to be present. Thanks for being present with me today. I have one more question. If you had one minute to speak to the world about anything, what would you say?

I’d probably tell a fart joke.

Be serious.

I don’t know, I feel like the world is serious enough. And going back to this whole idea—God is everywhere, God is in everything. There’s no such thing as “not God,” even the lowest lows and the highest highs. I think that attaching any kind of significance to the highest highs or the lowest lows beyond a certain point is a fool’s errand. Don’t attach so much to when something goes wrong or when something goes right. Just observe it, just watch, and watch what happens inside of you as you’re observing what’s going so right and what’s going so wrong and everything in between. To me, that’s where life gets really, really exciting and really beautiful. You start paying attention to all of the things that don’t mean anything to most people—but God is in all of those things.

So I suppose that’s what I would say. And tinge it with a fart joke. Or just fart after I say all that. Just like, [lets out pretend fart and sighs]. Thank you.

Loved Our Interview with Incubus Lead Singer Brandon Boyd? Deepen Your Learning Here.

Award-winning singer and songwriter Melissa Ethridge credits plant medicines for changing her life. Now, she’s started a nonprofit to help legitimize psychedelics with research. She tells her story to musician Shyla Rae Sunshine.

Music can impact the psychedelic experience. A new study explores how different genres can impact psychedelic therapy. Read the full story by journalist Jennifer Boeder.

Through participating in rituals with the Huni Kuin, ayahuasca and otherwise, Artist Naziha Mestaoui got what she was looking for: the opportunity to experience different realities. Watch her recordings of the vibrations of ayahuasca songs projected onto water.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.