To discuss the global community that has developed around the central African shrub known as Tabernanthe iboga is to discuss complex patterns of profound healing, colonization, and conflict. Many powerful traditional medicines that have been “discovered” by colonizing nations have histories of being exploited, but what’s uniquely interesting about iboga is that its psychedelic properties simultaneously link it to various communities that contain elements of both healing and violence.

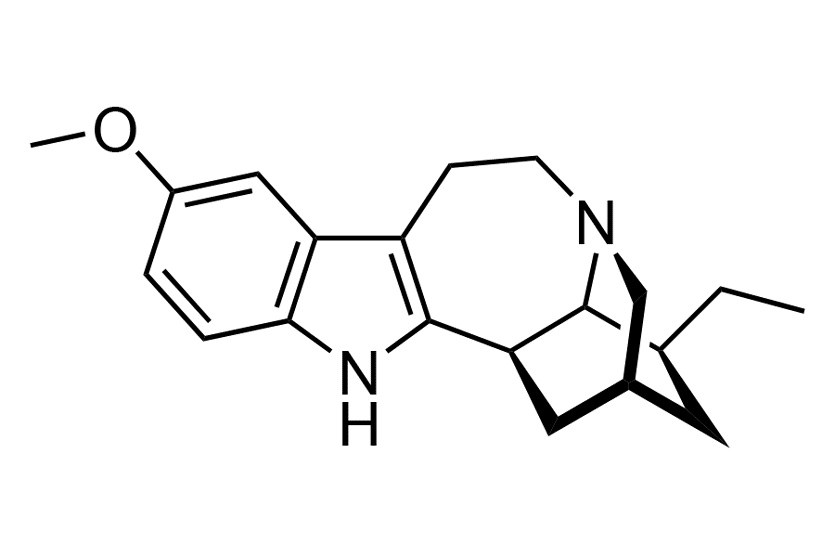

The stewards of this plant are the practitioners of Bwiti in Gabon who have frequently struggled to find support and protection from their government and the international community against illegal poaching and religious persecution. Iboga’s main alkaloid—ibogaine—has connected this plant to the world of substance abuse treatment in the West, which has bloomed into a thriving international, and sometimes underground, treatment community. Ibogaine’s powerful healing potential has also caught the attention of doctors, researchers, and investors since 1864 in France when Dr. Griffon du Belay of France first investigated iboga. Most recently, ibogaine and it’s metabolite noribogaine became a part of the portfolio of the largest publicly traded psychedelic company, ATAI Life Sciences (but more on that later). With each of these three realms come multi-layered ethical concerns that have often been glazed over by the evangelical zeal generated by iboga’s powerful healing potential.

Bwiti Iboga Use and Conservation

Iboga was first utilized by the Pygmies, the original group inhabiting Gabon and surrounding areas. Other groups, like the Bantu and Fang, migrated to the area over time and were introduced to the use of iboga by the pygmies through their spiritual practice known as Bwiti. Bwiti is an animist belief system based on ancestor worship and animism; iboga is used during their initiation rituals and for other healing purposes. The main goal with the use of iboga is community healing, spiritual growth, and to address various health issues.

There are certain sects of Bwiti that incorporate elements of Christianity, like the Fang who practice a syncretistic version, which arose out of a need to assimilate during colonization. In southern Cameroon the type of Bwiti practiced is called Ziliang/Mimbiri. Throughout the 1900s, Catholicism stigmatized and condemned Bwiti and its use of iboga. In more recent years, the conservative Evangelical church has been the main threat to Bwiti practitioners. It has even been considered evil or “of the devil” by the majority Christian population of Gabon. While some Gabonese hold respect and reverence for these traditional practices, there also still remains a prevalent attitude of fear and contempt that hampers the progress of conservation and protection for Bwiti and iboga.

The Nagoya Protocol, which was ratified in Gabon in 2011, prioritizes the use and benefit of “genetic” (i.e. indigenous) resources, such as iboga, for the traditional people who use them; yet this didn’t immediately translate into regulatory action in Gabon. Yann Guignon, founder and CEO of Blessings of The Forest (BOTF) social organization (Community Interest company based in UK + NGO based in Gabon) which is dedicated to the conservation of cultural & natural heritage of Gabon, has been working toward greater protections for Bwiti and iboga from the Gabonese government since 2004. He co-founded BOTF with David Nassim under the supervision of Professor Jean Noel Gassita (the oldest living iboga/ine researcher), and in 2012 he submitted a report to the Gabonese government (through the 1st lady foundation) about the illegal trafficking of iboga. Most of the iboga and ibogaine sold online is from plants that have been stolen from the protected forests by poachers and sold to consumers in the West. “95 percent of the iboga(ine) sold online is from trees that have been poached from the Gabonese public domain, reserved for local traditional Bwiti practitioners, and from the protected national parks of Gabon,” Guignon told DoubleBlind.

His report helped lead the government of Gabon to suspend the export of iboga in January of 2019. “BOTF’s lawyers have been drafting and defending for years a bill to stop the export of iboga from Gabon as a precautionary measure until the Nagoya Protocol is implemented,” said Guignon. “This text was adopted by the Council of Ministers in February 2019 and BOTF obtained a five-year agreement from the Gabonese authorities to develop a fair and sustainable public iboga industry based on the Nagoya Protocol.” The only way around this is to fill out an application form for the access and use of iboga in accordance with the Nagoya Protocol. Even though this doesn’t offer full proof against the illegal trafficking of iboga, it’s nonetheless a step in the direction of getting more extensive protection from the government of Gabon.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Guignon has been collaborating with the government of Gabon since 2006, and through BOTF since 2015, to create a legal, fair, and sustainable iboga industry that prioritizes access to iboga for the traditional people who use it and which facilitates the eventual establishment of an international market.

But to slow down the illegal poaching of iboga, the international community of ibogaine providers, as well as individuals who order from online sellers, must also be conscious of their impact. “Buying iboga without indisputable proof of its origin is not only totally illegal, but it is also responsible for the extermination of all kinds of protected species, notably elephants, panthers, pangolins, gorillas,” said Guignon, who also has worked with the anti-poaching unit Conservation Justice (CJ) NGO (Eagle Network) in partnership with the Gabonese government since 2016.

Gabon is divided into the public domain, national parks, and the private domain. Iboga growing in the public domain is reserved for Ngangas and Nimas, the leaders in Bwiti tradition, but according to some reports, iboga is currently endangered in the public domain. Iboga in the national parks is massively poached and only a few people are planting in the private domain, not enough to meet international demand. One clear way for ibogaine providers to support communities in Gabon is to use ibogaine made from the bark of the voacanga tree, which contains an alkaloid called voacangine that is easily converted into ibogaine (which can be derived from plants other than iboga). Voacanga grows across a much larger region of west central Africa than iboga does, and it grows faster. One of the reasons that creating a sustainable supply of iboga is so challenging is that the iboga plant must be minimum five to ten years old before harvesting in order for there to be a high enough concentration of ibogaine present in the root bark. If most clinics and providers outside of Africa would switch to ibogaine converted from voacangine, this would help give iboga an opportunity to replenish. Unfortunately, many practitioners hold the belief that “the spirit of iboga” will not be present when using voacanga-sourced ibogaine, despite the many successful treatments that have been done with this form of medicine.

Cultural Appropriation and a Lack of Reciprocity

Besides the issue of the physical poaching of the plant, there is also the issue of cultural appropriation and a general lack of reciprocity with Gabonese communities. Bwiti-style retreats, often run by mostly white people, are becoming increasingly popular across Costa Rica, Mexico, Canada, and even in the US. While some Gabonese feel like the allyship of foreigners will help to get Iboga protected and destigmatized within Gabon, there is also concern that Bwiti and iboga are being used exploitatively. Colonization has created a foundation of fear and a mistrust of foreigners—and colonization is not over. The so-called “psychedelic renaissance” is full of colonizing practices, with people from the West cherry-picking traditions and rituals for their own personal benefit. In this way, indigenous traditions have become decorative items used to display clout and exert authority in order to gain power, prestige, and income.

There also exists the perspective among some communities in Gabon that the international interest in iboga, and the foreigners who come to visit, are helping to elevate the status of Bwiti practitioners within the country and in the eyes of the government. According to the Iboga Community Engagement Initiative Phase 2 Report from The International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service (ICEERS), some Bwiti practitioners view foreigners as helpful allies, whose appreciation of iboga and Bwiti will act as helpful tools to reduce the stigmatization of their traditions. But the power dynamics that underlie this were born out of a violent system: It was white colonizers who brought Christianity to Africa to erase local traditions, but now white visitors are seen as necessary in order to save the traditions. As a concerned activist in the iboga space, I see how this could be a way to positively utilize the privilege of foreigners in order to elevate communities with less privilege, but it also leaves room for exploitation to occur. Those wishing to use their privilege to support Bwiti practitioners in Africa need to stay aware of the potential damage that toxic individualism can bring to indigenous cultures—and specifically, must be self-aware enough to not co-opt indigenous traditions for financial gain, social benefits, or to have power over others.

Marie Claire Eyand “Étincelle Divine” and Christophe Mathelin “Makondja” are two Nimas (the spiritual leader of the village in Bwiti) who told me that there are two types of ceremonies that foreigners practice. “With regard to the ceremonies practiced in the West, there are two kinds,” they both said. “The first are practiced by those who want to make money to the detriment of mentally low people. Knowing that a single dose of sacred wood (iboga) can start changing the perceptions. They only use the Bwiti ritual and therefore the results are insignificant. The second concerns honest insiders who wish to bring to their candidates an approach to the invisible world”.

What’s being described here is the phenomenon of opportunistic Western iboga facilitators who exploit vulnerable clients, using Bwiti rituals as a performative element without fully learning or integrating their true essence. The second part describes those who have shown respect and reverence for Bwiti and perhaps have taken the time to study in Gabon with Nimas or Ngangas. According to Etincelle Divine and Makondja, the latter route allows them to properly facilitate those seeking healing and spiritual development with iboga.

So how can one know which facilitators are genuine and which aren’t? Some of these retreats are connected to Gabonese Nimas who the retreats claim have given them permission to call what they do Bwiti in exchange for shared financial benefits. But does this financial exchange equal reciprocity and respect for the traditional users of Iboga? In my opinion, it is highly problematic for a foreigner to be making an income off of a tradition and a medicine that isn’t theirs, while the real keepers of these traditions struggle to get protection and access to their own medicine. What seems clear to me is that any foreigner profiting off of iboga or ibogaine should be making efforts to ensure the protection of Bwiti and iboga.

It is highly problematic for a foreigner to be making an income off of a tradition and a medicine that isn’t theirs, while the real keepers of these traditions struggle to get protection and access to their own medicine. What seems clear to me is that any foreigner profiting off of iboga or ibogaine should be making efforts to ensure the protection of Bwiti and iboga.

Besides the issue with retreats, international companies are currently acquiring patents and investing in Ibogaine research, but with no publicly stated benefit going to the communities in Gabon and little to no acknowledgement of these communities at all. I asked Jeremy Weate, former CEO of Universal Ibogaine, an organization working towards the establishment of an ibogaine clinic franchise, about what he thinks the impact of investor capitalism might have on Bwiti communities. Currently, there are a number of profit-driven companies seeking to patent (or already have patented) ibogaine, its related intellectual property, and even ibogaine treatment protocols. “Already, financial flows have led to the development of fully synthesized ibogaine, which ends any reliance on sourcing ibogaine from Tabernanthe iboga or any other plant material,” he said. Weate is describing the investment-driven development of an industry that hinges on synthetic ibogaine, bypassing the need to source plant material from Africa at all. Although this is beneficial, this does not cover all the bases of honoring and protecting the traditional users of iboga.

True reciprocity is not only about changing medicine sourcing from its native region to a lab, it’s also about acknowledging and respecting the community where iboga comes from and sharing with that community the economic benefits, which come from the rapid expansion of the ibogaine treatment market. Without this, patterns of colonization will continue.

Ibogaine Research

Howard and Norma Lotsof developed and promoted the use of ibogaine in the U.S. and Europe, having worked since the 1960s to develop ibogaine treatment for people with substance use issues after Howard’s own surprise discovery, at the age of 19, that ibogaine interrupted his heroin dependence. Thanks to the Lotsofs’ extensive work in The Netherlands and in the U.S., in 1993 a Phase 1 dose escalation study was approved by the FDA and administration of ibogaine to human subjects began. Unfortunately, the study was cancelled because of contractual and intellectual property disputes, according to some who were close to Lotsof. Further research was initiated by Dr. Deborah Mash, a neuroscientist and researcher at the University of Miami, who was introduced to ibogaine by Lotsof. Her extensive research has been focused on ibogaine and noribogaine, the metabolite of ibogaine produced in the liver that is responsible for the effects of ibogaine on the brain. Dr. Kenneth Alper, a psychiatrist and researcher at NYU, is another key ibogaine researcher who has published research on the neuropharmacological and toxicological aspects of ibogaine and is one of the most cited researchers in ibogaine presently. There are many other researchers who have contributed valuable work to the field of ibogaine knowledge, but Howard Lotsof, Dr. Alper, and Dr. Mash are amongst the most significant contributors.

Dr. Mash founded the company DemerX in 2010, subsequently establishing intellectual property rights around various aspects of noribogaine and protocols which use it. DemerX has now partnered with ATAI Life Sciences to fund and navigate through Phase 1/2a FDA trials with noribogaine. DemeRx is working towards FDA approval of clinical ibogaine treatment for opioid detoxification and the use of noribogaine in low dose form as a follow up treatment. This would be the first FDA approval of ibogaine or noribogaine. ATAI Life Sciences is focused on mental health drug development and offers funding and expertise to various psychedelic drug development companies, including DemeRx.

While there is a need for further research on ibogaine to increase safety and access, many in the community are concerned about ibogaine being controlled by a single profit-driven company. This belief, which I and other activists hold, is informed by the controversial reputation ATAI has earned in the psychedelic therapy community, especially following the attempt by Compass, who is under the ATAI umbrella, to patent various aspects (like hand-holding and soft furniture) of psilocybin-assisted therapy. Other psychedelic research institutions, such as the nonprofit Usona for instance, have gone the route of open source science, which could allow room for many to benefit, rather than consolidating benefits to a few.

Various studies have taken place outside the U.S., including in New Zealand and in Brazil’s Sao Paulo state (ibogaine is legally prescribable in both places). Dr. Bruno Rasmussen Chaves, a doctor and researcher who has played a significant role in developing ibogaine treatment in Brazil, reports that “the next step in Brazil is to fully legalize it [which] could happen in around three years, depending of course on other factors.” With what he calls a “receptive legal environment…Brazil will start producing and legally exporting GMP quality ibogaine by the end of the year, and we have already Phase 3 research approved by regulatory authorities which will finalize the path to full legalization.”

Meanwhile in Canada, after a series of deaths and hospitalizations during or right after ibogaine treatments, the government moved to restrict access to ibogaine by placing it on a Prescription Drug List. But the lack of clinical trials still stands in the way of it actually being available for treatment. This change in regulation has led to the shutdown of ibogaine clinics across Canada, some of which had been running since the early 2000s. Outside of these places, ibogaine is either outright illegal—like in the US—or it’s in a legal grey area. Mexico is an example of the latter, meaning that there are no current regulations regarding ibogaine, and clinics there are operating outside of any regulatory oversight.

Mindmed, a company developing psychedelic medicines that’s based in the U.S., is doing research on 18-MC, a synthetic derivative of ibogaine. They are developing 18-MC for the treatment of opioid use disorder and are soon to initiate Phase 2 trials to confirm that it reduces opioid withdrawal symptoms. 18-MC has no psychedelic effects and, according to their Phase 1 trial, no cardiotoxic effects. While anything that reduces withdrawal symptoms is significant, ibogaine without the visionary experience is not comparable to the full experience. In my opinion, the benefits of 18-MC won’t be nearly as far-reaching as those of iboga or ibogaine. There has also recently been research on iboga analogs called oxy-iboga compounds, which are reported to have no cardio-toxic side effects as well.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

I authored an article in 2020 detailing why standards of care are lacking in ibogaine treatment, but one of the reasons is that there is no training or supervision structure to support facilitators in following the clinical safety protocols. Many ibogaine advocates are focused on getting clinical trials in the U.S. in order to get ibogaine treatment approved and monitored. They believe that the approval of ibogaine, and its subsequent integration into medical systems, guarantees safety because of the standardization of training and protocol. One of the issues with this is that in the U.S., the medical system leaves many people traumatized from systemic racism and a lack of trauma-informed training, amongst a long list of shortcomings. Placing powerful psychedelics in the hands of a system that has unaddressed oppressive practices may put people at risk of more harm. While the Western ibogaine treatment community is definitely in need of more training and support, it’s just not clear to me that government involvement is the answer, even if it is the doorway to more access.

Much of ibogaine treatment in the West occurs in clinics dotted across Mexico, Costa Rica, a few in Colombia and the Caribbean, and in the EU. The quantity of clinics has grown rapidly in the last 20 years, originally thanks to Howard and Norma Lotsof and some of the people they trained. The amount of new players in the treatment community is ever-increasing, and the type and quality of treatment on offer varies greatly. The following sections will explore more deeply the various aspects of treatment and the types of people involved.

Is Ibogaine Safe?

Since the international community of ibogaine clinics and providers is one that lacks an overseeing body, certification process, or supervision process, finding a safe and quality facility for treatment can be extremely challenging. Due to ibogaine’s cardiotoxic side effects, adherence to clinical safety protocol is non-negotiable. In 2016, the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance (GITA) published the Clinical Guidelines for Ibogaine-Assisted Detoxification, which was a huge step forward in working towards a safer ibogaine treatment community. Unfortunately, there is no way to enforce or guarantee that every clinic or provider abides by these standards.

Ibogaine causes a slower heart rate (bradycardia), as well as something called a prolonged QT interval, which is the time it takes for the ventricles of the heart to contract and relax. When this interval is prolonged past a certain point, the heart goes into a deadly arrhythmia called Torsades de Pointes, which leads to cardiac arrest. This actually happened to me during my first ibogaine treatment because the facilitators weren’t following safety protocols, but these risks could have been modified with adherence to proper protocol and medical screening. Among a long list of contraindicated conditions, any history of cardiac issues eliminates eligibility for ibogaine treatment.

The cardiotoxic side effects of ibogaine affect virtually everyone to some degree. For many people, the level of lowered heart rate and prolonged QT interval are small enough that it can be safely managed, but for others it can enter into a more dangerous zone. There are many factors which could influence these cardiac effects, among them are the substances people have been using recently, various medical conditions, improper electrolyte balance caused by excessive cleansing or vomiting before treatment (like with kambo), administration of too high of a dose of ibogaine, and medication use that has not been properly disclosed. The mortality rate for ibogaine is challenging to determine. Many past fatalities were mostly avoidable—had the proper protocols been followed.

There are some basic things to know in order to decipher between a safe and unsafe clinic. The first key element of a safe ibogaine treatment is the medical screening process. Any cardiac history including arrhythmias, congenital heart defects, and heart murmurs are rule-out conditions. Before a person is even approved to go to a clinic, prospective clients must get an EKG (electrocardiogram) done and subsequently approved by a doctor familiar with ibogaine or a very experienced and trained ibogaine provider. Proper liver function should be assessed through a blood liver panel to be reviewed by the medical team at the clinic. Prospective clients must also be completely honest about what substances and other medications they use. Certain substances and medications, or the sudden withdrawal of these, will increase the fatality risk when used in combination with ibogaine. If a clinic is not asking for EKGs, a liver panel, or medical history in advance, nor are they offering them upon arrival, this is a major red flag.

There are many substances which require careful consideration when used close to, or during, ibogaine treatment, but one of the most important to mention is benzodiazepines (for example, alprazolam, diazepam, and clonazepam). Benzodiazepine withdrawal places people at increased risk for seizure, and when a seizure is combined with the cardio-toxic side effects of ibogaine, you can almost guarantee this will lead to a prolonged QT interval, the deadly rhythm Torsades de Pointes, and subsequently cardiac arrest. Many of the recorded fatalities and hospitalizations are due to the mismanagement of benzodiazepines during the treatment. One of the core tenets of safe ibogaine treatment is that if someone arrives already on benzodiazepines, they must stay on them throughout the treatment at their usual dosage. This is completely safe as long as the client’s regular dose is administered. It’s also ideal for the clinic to use diazepam during ibogaine treatment in an equivalent dose to their normal benzodiazepine, because its duration is longer and more stable. If a person wants to get off their benzodiazepine medication, this requires a long and slow taper to be completed well before ibogaine treatment or well after. The best protocol for this is the Ashton manual. To make it clear: You can not use ibogaine to detox from benzodiazepines.

Another key issue in ibogaine treatment is the differing protocols for different opioids. Short-acting opioids like pure heroin, oxycodone, and morphine, can be used up until arrival at a clinic. Once at the clinic, a client will be stabilized with morphine or oxycodone for a few days or more prior to treatment. Fentanyl requires a different approach because of its QT-prolonging effect and its tendency to leave the system more slowly and cause longer withdrawal effects due to being lipophilic (fat binding). With this, it’s necessary to switch to another short-acting opioid for two weeks prior to ibogaine. Unfortunately, the majority of street opioids in the U.S. currently contain fentanyl, and even pills that look like oxycodone now contain fentanyl. This relatively recent development has made ibogaine treatment more risky, more expensive, and more time-consuming because most people do not have access to pure short-acting opioids. Some clinics are offering two weeks of stabilization time pre-treatment, but this additional cost is unaffordable to many.

Suboxone and methadone are long-acting opioids which leave the system very slowly, resulting in months of withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, ibogaine does not allow you to skip this process. For the best results, suboxone and methadone users should plan to switch to a short-acting opioid for six weeks or more prior to ibogaine. Like I said before, this is very tricky because real short-acting opioids are hard to come by, with almost no street availability and very few doctors willing to prescribe for this purpose. Going to ibogaine treatment too soon after a long-acting opioid dependence will result in a person experiencing serious and lengthy withdrawals post-treatment.

The one exception to the suboxone and methadone rule is the low-dose protocol pioneered by Clare Wilkins of Pangea Biomedics, a key figure in the development of treatment protocols, who has been working with ibogaine since 2006. Most clinics practice the method known as “flood dosing,” which involves one large dose of ibogaine in one night. Clare’s revolutionary low-dose protocol involves between two to five weeks of daily small doses of ibogaine (or other forms like TA—iboga total alkaloid extract) that gradually increase, along with doses of a short-acting opioid at a different time of day that gradually decrease. In this way people can slowly step down from opioids and will not need to make a lengthy switch to short actings beforehand. This method is also very safe as the doses are much lower than those used in the flood dosing method, thus reducing cardiac risks. EKGs, blood pressure, and pulse are checked multiple times daily to monitor the cardiac response to the dosing, so it’s not a protocol a person should try on their own. Besides the safety benefits, this protocol is much more gentle and gradual, allowing people to better integrate and understand the insights that ibogaine provides. The organization ICEERS has utilized Wilkins’ protocol in a study on detoxification from methadone.

In many clinics, some of the most basic requirements for a safe Ibogaine treatment (example: EKGs for pre-treatment screening, drug testing upon arrival, automatic defibrillator on-site) are not being followed. I recently interacted with the head of a long-running clinic in Sayulita, Mexico, who told me they do not ask for EKGs, nor do they perform one prior to treatment. This is the most essential and basic thing needed to ensure that any potential cardio-toxic side effects are minimized. Another well-known clinic in central Mexico recently had a hospitalization due to a seizure because they decided to reduce their patient’s benzodiazepine medication in the days prior, and during, their Ibogaine treatment. This is yet again the breaking of a basic ibogaine treatment protocol, which is that you do not under any circumstances reduce or stop benzodiazepines close to, or during, ibogaine treatment. The knowledge to avoid both of these errors are considered Ibogaine Treatment 101.

“In an industry where the primary goal should be client safety and optimal treatment plans, there is a sea of new, old, untrained, and trained providers competing for attention, Google placement, and clients, often taking advantage of people in vulnerable states,” says Shea Prueger of Ibogaine Revelations, an experienced ibogaine provider who works in Costa Rica and Asia. Even providers with a wealth of negative reports, hospitalizations, and even fatalities continue to get clients because there is virtually no way to forcibly stop facilitators from working in the countries where clinics are operating. Often after a clinic has a death, they will simply close down and reopen with a new name.

Read: How Ibogaine Can Help With the Opioid Crisis

One such clinic in Baja that has done this multiple times also has numerous reports of allegedly sexually abusing female clients. One of these clients, who went for a six-month, multi-psychedelic treatment, witnessed the owner sexually abusing clients, extorting them for money, and using a plethora of substances himself. She told me that he “spent endless days and nights taking a myriad of drugs and engaging in various sexual activities with at least one, perhaps even two, female ‘private clients’ with their own houses far away from the main facility. These ‘private clients’ were rarely ever seen outside their homes and never in the actual facility…..He would boast to some of the other men at [the clinic] about having his ‘own little sex slut down the road’ and the amount of money she paid him for her treatment.” At this time, we are withholding key details of this case, as many who have come out against this center have been physically threatened. It is our hope and intention to do a kosher investigation in the future.

Unfortunately, holding dangerous people like this accountable has been a challenge for various reasons. Often, the accumulated knowledge of these incidents belongs to long-time working members of the community who have little to no ability to take action in order to address these dangerous practitioners other than spreading the word behind closed doors. One of the reasons why this is the case is that some of these clinic operators have cartel and corrupt police connections which they use to threaten whistleblowers. This fear of retaliation has scared many in the community into silence. Involving Mexican law enforcement is not guaranteed to be helpful either, since they are often easily bribed and can be slow to take action.

Safety in ibogaine treatment is clearly not only about proper medical protocol, it’s also about emotional and physical safety, as well. Another example of a dangerous practitioner is a well-known Gabonese Bwiti Nima, which many of the western Bwiti retreats support. He has numerous reports of sexually assaulting women and is wanted by the state of California for unpaid child support. But the survivors of his abuse unfortunately are also hesitant to speak out for fear of retaliation.

Even Though ibogaine is a Schedule 1 substance according to the United States Controlled Substance Act, meaning it is a drug that faces the strictest regulations, there are still underground providers working in the U.S. The issue with these treatments is that it’s challenging to maintain safety since medical professionals are mostly unwilling to be present due to the legal risks. Some states and cities have successfully decriminalized certain plant based psychedelics in recent years, but this does not mean that these medicines can be offered as a medical treatment just yet. Due to these circumstances, it is not recommended to participate in underground treatments. If a person chooses to, it’s ideal to do research and ask key questions to evaluate a provider for experience and assess if they offer proper medical monitoring. Myself and an experienced ibogaine provider created a guide for finding a safe clinic, which can be used to evaluate any practitioner.

Community Dynamics

The organization GITA has been responsible for some significant work in the ibogaine community. Howard Lotsof’s Ibogaine Patient’s Bill of Rights provided the basis for many projects including multiple international conferences, the Clinical Guidelines for Ibogaine-Assisted Detoxification, a patient advocacy program, and an ACLS (advanced cardiac life support) certification course for ibogaine providers. These projects have been essential in improving safety and quality in clinics across the community. In 2016, the executive director suddenly resigned and for over a year refused to hand over access to new hands. This caused a loss of momentum which the organization has never quite recovered from. Dr. Chaves reflected on the causes of this situation: “When came the time to take some key decisions, the individual interests of each other spoke louder and GITA simply disappeared. But it left a legacy that still persists and the cause shifted to a new level.” Fortunately, GITA is still somewhat active, with members receiving and processing reports of adverse medical events.

The interpersonal power dynamics behind the loss of momentum with GITA is at the root of some of the unhealthy tendencies in the community. “We are at a point right now where we really need to reevaluate not just treatment protocols and procedures, but screening processes, and it’s a time when we all really need to be working together,” Thom Leonard, an ibogaine provider who runs Anzelmo Ibogaine in Mexico, told me. “But that’s not happening. We are a very fractured community and there’s a lot of distrust and a lot of it rightfully so and a lot of it not…There needs to be more communication and collaboration.”

The Root Ibogaine Collective, a women and queer-led collective that I co-founded in 2020, has been working to support those seeking, and those working in, ibogaine treatment. One of the services we are offering is a grievance process, modeled off the GITA process, through which people can submit complaints about problematic clinic experiences. We are offering a space to listen and discuss difficult clinic experiences, and occasionally mediation with the clinic itself. We are also starting to hold regular Ibogaine provider support meetings which will provide a safe space to seek support, share experiences, and improve collaboration amongst people working in the community. Though these actions won’t necessarily solve the complex safety and ethical issues in the community, we hope that these projects will help pave the way towards bigger endeavors, such as a training program.

Besides the issues with adherence to safety protocols, there is also the topic of the untrained, and sometimes dangerous, people working in the community. “Many people become providers after a single ibogaine experience and move on to work with complicated mental health and medical diagnoses that they have no experience with under the guise of a medicine they believe to be a ‘cure-all,’” Shea Prueger says, describing the overzealous tendencies of some who have recently completed treatment. I’ve observed that many people working in the ibogaine treatment community were drawn initially towards this medicine because of their own need for profound healing, but nonetheless don’t have the necessary knowledge that they think they may have in order to hold space in a safe, effective way. Indeed, in my experience I’ve noticed that psychedelics can have “ego-potentiating” qualities that in some cases lead people—having recently done ibogaine—to suddenly see themselves as having power and knowledge in an unrealistic and narcissistic way. In other words, an unregulated and unmonitored community becomes a breeding ground for dangerous and unqualified practitioners. Placing vulnerable people under the care of unqualified practitioners can mean death, injury, sexual assault, and also continuing harm to the traditonal users of iboga in central Africa though cultural appropriation and lack of reciprocity.

Although there are talented facilitators running safe and quality clinics, finding them is not an easy task. Countless websites make sensationalistic claims to be the “most experienced providers in the world” or “safest clinic in the world” with no proof available to back these claims. The Guide to Finding a Safe Ibogaine Clinic that I mentioned earlier helps eliminate many of the unsafe clinics in operation, but it is not entirely foolproof. Finding a safe clinic requires diligent communication, research, and an ability to differentiate between marketing tactics and a practitioner who actually wants to help people find the treatment that’s right for them.

Thom Leonard has witnessed and experienced many of the challenges of the community, including the serious burden that fentanyl has brought to the ibogaine treatment world due to the extra stabilization time that is needed. “The days of seven-day treatments are pretty much over with, we have entered a new era with ibogaine,” says Leonard. “Some people are aware of it, some people are unaware out of ignorance, and some people are willfully ignorant of it because they’re still trying to make a buck. That’s where things need to change.” Some clinics rush treatments along for financial reasons, but this puts clients at risk of serious medical complications and even death.

The highest concentration of clinics is in Mexico because of its proximity to the U.S. and its citizens, who are some of the most financially privileged people in the world. A treatment at a clinic, which costs between $5000 and $15,000, is just not accessible for many populations. Some clinics offer the occasional free or low-cost treatment, but there are currently no grants or scholarships on offer from any organizations (which is hopefully soon to change). The majority of the people I see being able to afford treatment in Mexico are white men from the US and Europe. Women do access treatment too, but not as often. BIPOC are even less likely to be seen at clinics. The fact that it’s mostly white people who are able to access this treatment is highly problematic given that iboga is an indigenous medicine. Ideally, more financial support should be made available to support access to treatment for all.

Mental Health Support in Ibogaine Treatment

Professional mental health support varies greatly between clinics and retreats. Some clinics have multiple psychologists and psychotherapists on staff, some utilize recovery coaches only, and some rely on their staff to offer psychological support. Proper mental health support is critical since the ibogaine experience can trigger major trauma to come up and sometimes even psychosis. Some of the Bwiti retreats depend on the Nganga and their traditions to take care of the psychological support, but often this is not sufficient for people struggling with complex mental health issues. Ideally, a clinic has a trauma-informed psychotherapist on staff or one that they bring clients to outside of the clinic.

Post-ibogaine treatment continuing care has improved somewhat in recent years, with a few quality places offering multiple weeks of residential care for post-ibogaine clients. I visited Inscape Recovery in the mountains outside of Mexico City a few months ago, and was excited to see the program they had on offer which includes group and individual therapy, personalized naturopathic doctor consults, fresh organic food grown on-site, and other therapies. Coaches and therapists focusing on preparation and integration around ibogaine treatment are increasingly available through virtual and in-person meetings as well. For many the affordability of the actual ibogaine treatment is an issue, with families barely able to scrape together enough money to pay for the treatment itself. The average cost of a 7-10 day flood dose treatment is around $8500. Often this can mean that affording the cost of support for afterwards is challenging.

Read: Are Ketamine Clinics Paving the Way for Legal Psychedelic Therapy?

Another factor in the quality of an ibogaine treatment is the philosophies being utilized in ibogaine clinics. Most modern addiction treatment is based on the mainstream “disease of addiction” and 12 step program-based school of thought. These philosophies tell individuals that they have a disease for life which is unchangeable and they demand acceptance of the concept of “powerlessness”. This is the philosophical approach that unfortunately many ibogaine clinics are using. One issue with this approach is the hyperfocus on individual accountability, which does not acknowledge the systemic oppression at the root of many people’s trauma which has led them to struggle with their substance use in the first place. It is born out of a one-size-fits-all mentality that utilizes stigmatizing and dehumanizing language, like the word “addict,” and adheres to the narrow definition of success that is “abstinence only.” While this approach is an effective tool for some, and any tool that helps is valuable, for many it can be re-traumatizing after a lifetime of already feeling disempowered by a dominating capitalist culture that values human beings based on their productivity. Many individuals who have substance use issues have a history of being punished and shamed for not conforming to the system of obedience and production that capitalism requires, so imposing a recovery structure which has a one-size-fits-all approach can disconnect people further from their own inner power. It also leaves little room for the exploration of the unique and complex factors that have led people to be who they are. In my opinion, this kind of restrictive and narrow approach to healing is not the best accompaniment to a medicine that is supposed to be about expansion, empowerment, and embracing one’s authentic path.

Fortunately, some ibogaine providers like Clare Wilkins and Shea Prueger work from a harm reductionist philosophy. This approach embraces each person’s journey as unique, while also creating an atmosphere which allows clients to define what success means for them, rather than imposing a single definition of success. It also offers people a re-connection to their inner power and a possibility to return to the original state of intuition and self-trust that we are all born with. The philosophy of harm reduction is an essential accompaniment to ibogaine treatment because the vast possibilities and insights that ibogaine reveals to people demands a philosophical approach that has space for a variety of healing journeys. For some, Bwiti practices also offer a pathway to this inner re-connection as well.

What is Ibogaine Treatment Like? The Mechanics of the Ibogaine Experience

Outside Gabon, ibogaine has received the most notoriety for treating opioid use disorder because of its ability to help the body seemingly “skip” the majority of opioid withdrawal symptoms. Ibogaine’s mechanism of action is unknown, and it differs from any other opioid treatment approved for opioid use disorder. Some researchers say it is a mu-opioid agonist and some say it is not, but it is not a substitution therapy like buprenorphine or methadone. But the benefits of ibogaine are not limited to opioid users; people who use other substances, like cocaine, methamphetamine, and alcohol, also experience profound transformations as well. People with mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD, can also potentially find deep healing with ibogaine because of the renewing effect it has on multiple receptor sites of the brain. Ibogaine has also been used to a limited extent in very small daily doses to help alleviate symptoms in people diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. Although these reports are anecdotal, there is research showing that ibogaine administration enhances the expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the brain. GDNF and BDNF are neurotrophins that are responsible for the regeneration and survival of neurons in the brain. Dana Beal, a legendary ibogaine advocate and integral member of the community, has worked tirelessly for the advancement of further research on this topic.

While the root bark of T. iboga is used in traditional Bwiti practices, most clinics doing treatments for substance use issues are using pure ibogaine HCl (hydrochloride) because of the higher doses needed for drug detoxes and the lack of research available on the other alkaloids in iboga. Some clinics use something called TA, or total alkaloid extract, which has a higher concentration of ibogaine than in the root bark, but still includes the other alkaloids. There is also something called PTA (purified total alkaloid) which is 90 percent or more of ibogaine and a small percentage of the other alkaloids. Preference varies per clinic as to which form of medicine is used, but ibogaine HCl tends to be the easiest and safest to predict and control. The part of the root bark that is used from T. iboga is the second layer between the wood fiber of the root and the outer bark of the root and is usually administered by the spoonful in the form of a mulch-like, and sometimes powdery, substance in traditional Bwiti ceremony. Ibogaine HCl is a white to off-white powder administered in capsules. PTA and TA are brown and in a powder form, administered in capsules as well.

During the experience of a flood dose, a person is laying down with their eyes closed, having dream-like visuals, but without actually being asleep. They are able to respond to simple questions with a slight delay, but are very much immersed in their visionary experience. These visions are quite different from psychedelics in the hallucinogen category, as ibogaine is a dissociative psychedelic with oneiric (dream-like) properties and is not a hallucinogen. The visions happen with closed eyes and resemble an actual dream. People report a variety of experiences including speaking with ancestors, traveling to Africa, reliving repressed childhood memories, random images that don’t seem to make sense, and some even don’t remember their visuals at all. Often people report the experience of sorting through their brain, as though it is a filing cabinet, and physically throwing items away. A person can’t walk or stand without assistance because ibogaine causes a severe lack of balance (ataxia). These primary effects last eight to twelve hours after which there is an eight to twenty-four hour integration period (depending upon a person’s metabolism) in which a person is resting and processing the experience. Some refer to this as the ‘grey day.’

The dosing with any form of this medicine (iboga bark, TA, PTA, and HCl) is not straightforward and is dependent upon a person’s EKG, blood pressure, pulse, medical history, and response to a small test dose. In initiation ceremonies in Gabon, I have heard of doses ranging from 30-70 spoonfuls. In clinics flood dosing with ibogaine HCl, doses range from 10-22 mg per kg of a person’s weight. But determining the proper dose is contingent upon a variety of factors that can only be assessed by an ibogaine treatment experienced medical professional or provider. The dosing with the low-dose method also must be done under the same quality of trained supervision. Although medical monitoring is not available during initiation ceremonies in Gabon, traditional Bwiti practitioners are not detoxing off of substances and they often are without complex health issues, unlike people in the West who are approaching treatment in clinics. Regardless, fatalities also do happen in Gabon.

Obtaining medicine outside Gabon, or inside, is not a straightforward task. There are few sources that are able to provide a guarantee that they do not use iboga poached from protected forests. I know of a source that uses plants grown in a plantation in Cameroon, but official verification is difficult to procure. The safest sources only sell to established clinics that come with references, which is done to prevent people from doing large doses outside of medical supervision. Those wanting to obtain iboga products for their own personal use will most likely be buying from illegal sources or they will be sent plant products that aren’t even iboga. Iboga World, based in South Africa, is one of the well-known online providers of iboga products. They have repeatedly refused to provide verification for their sourcing and the dosing instructions that they give to people are often extremely dangerous. It’s highly advised to avoid taking any iboga product outside of medical supervision and consultation.

There are many who attempt to order medicine online and use it at home by themselves because they can’t afford the price of a clinic. While it’s unfair that only privileged people can access safe clinical treatment, it is extremely unsafe to take iboga without professional medical supervision, especially for drug detox purposes. Facebook groups and other sites provide a place to share advice about dosing and other recommendations, but often the advice is incorrect and unsafe. The safest bet is to find a clinic that offers the occasional low-cost treatment for people who are lacking in resources. For information and advice, the ibogaine Reddit is currently moderated by experienced and knowledgeable people from the community.

While iboga and ibogaine have an amazing potential for healing, neither one is a panacea nor a cure. Any pathway of healing requires a unique combination of various healing tools, lifestyle changes, radical vulnerability, and an ability to self-reflect. These are things that don’t just “work” overnight, but they take daily, relentless, and long-term effort and integration, as well as community support.

This same quality of effort is required if we are to protect iboga and the traditional people who use it. Ensuring that Bwiti communities in central Africa are protected, honored, and compensated is going to require some shifts in perspectives and priorities from the international community of clinics, researchers, investors, and online buyers. Placing the needs of the Bwiti community first, before personal profit, is the first step. Unfortunately, I am not entirely confident that these shifts are yet on their way, judging from the actions that I’ve observed of organizations investing in ibogaine like ATAI Life Sciences and Universal Ibogaine. Yann Guignon wanted this message shared here:

“I would like the international community of iboga(ïne) promoters to show gratitude and respect to the Pygmy and Bantu peoples of Gabon for being the ancestral guardians of this sacred resource, as well as for having accepted to open up their previously secret knowledge to the Western world…. It is fundamental, for peace and balance between peoples, that the cooperation dedicated to the development of iboga is transparent, fair and sustainable… Not to try to build a lasting bridge between old and new medicinal technologies would be a serious mistake for the whole of humanity… What humanity could gain in return goes far beyond the hopes of freeing the world from the scourge of opiate addiction.”

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.