The rise of the witch archetype, both in modern culture (and in its initial incarnation as medieval-era paganism), coincides directly with eras rife with patriarchal suppression, religious extremism, and moral repression. As the cauldron of inequities boils, the witch mounts their broom and rides high across the moonlight sky. They may shapeshift, according to epoch and origin, but the essential elementals in their nature remain the same. Earth. Air. Water. Fire. A deep connection to nature, to the sacredness of soil and plants, herbs, trees, and flowers. Innate intuition, telepathic empathy, the acknowledgment of the existence of mystery and magic. The watery flow of the feminine—fluid and unconstrained by norms of gender. And finally, an intimate partnership with power, the willingness to be ignited by passion, sensuality, and righteous protest. The last is ancestral—a rage building upon centuries of violence and repression and the hard facts of the witch hunt genocides, just a few short centuries passed.

We are once again in a moment where issues of social justice, patriarchal power, and economic inequity are at the fore. We fight against racism and sexism, we march for our rights and strive to save our environment, even as our screens sever our inherent connection to the natural realm. The time is ripe for the re-emergence of the witch. And so the archetype has once again stepped out of the shadows and into our cultural consciousness.

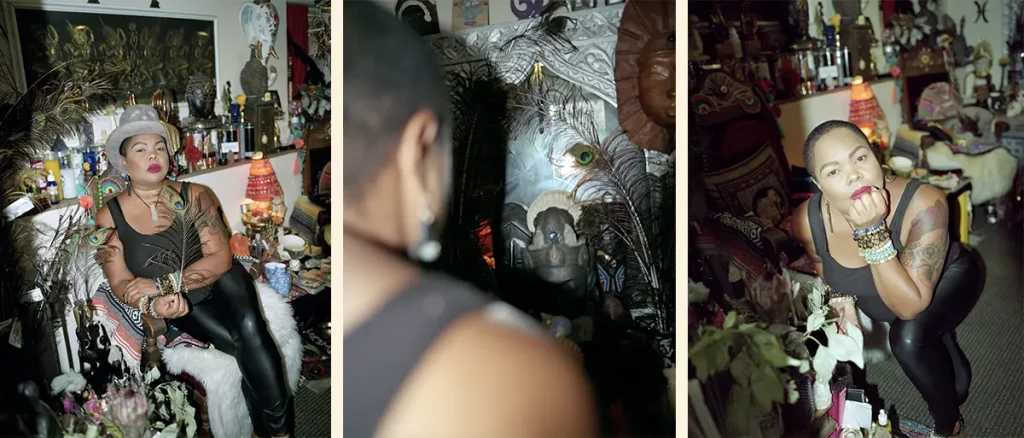

Today, the modern witch manifests in a myriad of forms—artist, activist, healer—its shape always shifting. Social media platforms have allowed the witch both voice and connection with coven communities emerging online and thousands utilizing the power of TikTok (better known as WITCHTOK) to express their beliefs and define their practice. And while to identify as a witch remains dangerous (particularly in certain areas of the world), it has become more and more a unifying battle cry from those at the forefront of our creative and philosophical evolution. The modern witch encompasses a vast range of identities and expressions. Practitioners of the contemporary craft are most likely to defy definition and to honor the full spectrum of identifiers like gender or race. Ritual is considered a method of connection to the cosmos and the natural world, to our bodies and to each other. Rites are flexible and varied, depending on the type of tradition to which the modern practitioner feels most aligned.

The initiation into contemporary witchcraft is equally diverse. Some traditions are passed down through family and ancestral legacies; a grandmother that practiced Caribbean hoodoo or a mother who traced her ancestry to her Druidic roots. Some find witchcraft through friends and mentors. But many, if not most, modern witches come to their practice through an array of online and real life offerings, workshops, panels, and other gatherings held by a host of new era practitioners helming vast multimedia covens and spreading the word through books, magazines, social media, and live events. Utilizing technology and subverting propaganda to further the cause, witches have taken the internet, radio, TV, and podcast world by storm. Using the tools of the patriarchy to their own advantage, the element of rebellion is still inherent within the witch archetype, whether as a statement against the status quo or as it was generations ago, simply as necessity.

READ: Where Witchcraft Meets Plant Medicine

The persecution of the witch began in the early 1400s and continued across Europe and into America for the next 200 years or so. Hundreds of thousands were tried on trumped up charges, countless put to death under false allegations, tortured until they confessed and were subsequently executed. Both the Catholic and the Protestant churches were leaders of the charge, the sectarian battles between the two faiths resulting in turmoil. Political unrest and economic instability became harbingers for persecution to come—those in power placing blame on the poor, the weak, and the vulnerable. In scholar Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch, published in 2004, these trials were, she writes “the first persecution in Europe that made use of multimedia to generate a mass psychosis among the population.” With the invention of the printing press, came the advent of propaganda. Fingers pointed at those who dared to practice pagan faiths, experiment with psychoactive plants and fungi, educate themselves in midwifery medicine or herbalism or other natural healing techniques. Anyone who showed signs of non-conformity, sexual expression, or personal power were mostly doomed to hysterical allegations. These court-sanctioned witch hunts would continue unabated for centuries, until the Age of Enlightenment in the late 1680s eventually began to shift perspectives and philosophies.

The witch, meanwhile, went underground, the archetype awaiting its next incarnation. In the women’s fight for equal rights in America and Europe during the mid to late 1800s, the witch rose once again. Early suffragettes pointed to the witch as the bleakest example of patriarchal tyranny. In a speech in 1852, scholar and suffragette Matilda Joslyn Gage made this claim: “Witches too often were educated women who challenged existing power structures. No less today than during the darkest period of its history is the church the great opponent of women’s education.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Later and throughout the early 20th century, the witch would serve as inspiration for artists who would seek to transform the archetype into a reflection of their own complex identities. A circle of Surrealists that included Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Leonor Fini translated the concept of witchcraft into a representation of imaginative individuality.

Amid the counterculture revolution of the 1960s, a new era and new archetype emerged, the witch as activist. This moment saw the formation of the radical W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), an organization which fought for women’s and civil rights and whose manifesto read, “W.I.T.C.H. is the living remnants of the oldest culture of all—one in which men and women were equal sharers in a truly cooperative society, before the death-dealing sexual, economic, and spiritual repression of the Imperialist Phallic Society took over and began to destroy nature and human society.” The late 1960s and 1970s also saw the rise of new witchcraft traditions such as Wicca, a practice founded in England during the mid-20th century and drawing some of its core tenets from pre-Christian Celtic origins. Neopaganism, also popularized during the last century, is based in part on ancient European pagan religions. Throughout each era, the archetype of the witch finds various definitions, remaining fluid, adapting to, and reflecting upon the culture from which it came.

Whether drawing on and expanding upon ancestral tradition, looking to historical inspiration in matriarchal pagan cultures or utilizing magical practice to ignite creativity, witchcraft has always adapted to the needs and desires of the individual—and that remains true today, in its current iterations. “Sex Magick,” made popular in the early 1900s by the occultist Aleister Crowley, has been transformed by a new era of practitioners who find self-empowerment through sexual exploration. Another popular contemporary tradition known as Green Witchery celebrates our connection with the earth and natural world. Empress Karen Rose, author of The Art & Practice of Spiritual Herbalism, owner of the NYC-botanical shop Sacred Vibes, and a practitioner of green witchery, utilizes both ancestral and contemporary healing traditions in her herbs, teas, and tinctures. Raised in Guyana, Rose was exposed to African, Caribbean, and Latin American traditions that profoundly influenced her to take on plant medicine and community healing. “I consider myself the descendant of healers—the granddaughter of medicine people,” Rose explains, “The witches of Africa were and are powerful, and influence change in significant ways. My practice entails a close connection to nature, specifically plant medicine. A plant healer matches the energy of the plant with the energy of the person, and this can feel like witchery, like magic. But it’s also a healing tradition that goes back centuries.”

READ: There’s a Worldwide Spike in Arrests of Plant Medicine Practitioners

Pam Grossman, author of the best-selling book, Waking the Witch and host of the hugely popular Witch Wave podcast, takes a scholarly approach to the craft. She first came to witchcraft in her teenage years, seeking, as she describes, “strength, self-empowerment, and a deeper purpose” and since has deepened her practice through the close study of the witch archetype within art history, Jewish mysticism traditions, and ancient goddess and matriarchal societies. “It’s an archetype that is constantly shifting,” she explains, “but in many ways, you can define the witch as someone that uses the power of imagination and intention to create positive change, both in their lives and in the world.”

One of Grossman’s many protegees is drag entertainer Jinkx Monsoon, a winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race and current star of Chicago: The Musical on Broadway. Monsoon sees witchcraft as a way of, “thinking for ourselves, with an open mind and open heart.” For Monsoon, the fluidity and flexibility of the craft, the ways in which it empowers rather than restricts, is key to its allure. “Witchcraft is, and should be, personal to the individual,” says Monsoon, “We define our relationship with it based on our own needs and boundaries. You can be a witch at whatever level that works best for you—just be sure to make those decisions for yourself, and don’t let anyone else define your practice for you.”

For the majority of witches, one important way in which they personalize their practice is through integrating parts of their ancestry and lineage. “I am multiracial, so that in itself is reflective in my magic,” Bri Luna, founder of the multimedia platform, The Hoodwitch, explains. “The rituals and spell work that I practice infuse elements of both of my cultures. I find that I utilize aspects of traditional folk healing from my indigenous Mexican and African American ancestors, as well as working with practices from others that I feel resonate with me. ‘Does this feel right?’ is certainly a question I ask before partaking in any new ritual. I trust my intuition and let it guide me.”

In addition to witches who are focused on supporting others through offering them herbs and hosting rituals, there’s a new wave of contemporary artists integrating magical practice onto the gallery walls of the fine art world. Artist Edgar Fabián Frías is among them, using witchcraft tradition in the context of their performance, sound, and multimedia work. With work featured at numerous museums, Frías celebrates the fluidity of the witch archetype within their installations, sculptures, and films. Drawing on their own “indigenous, queer, pagan, witchy, mutagenic, and chimerica” facets, Frías embraces witchcraft traditions that, as they explain, “First and foremost, center relationships and honor the inherent wisdom that we each contain. Witchcraft is a space of communion, with the earth, the moon, the sun, the birds, the flowers, the bees, the faeries, our beloved ancestors, queer ancestors, and transcestors, spirit guides.”

There’s also witches, such as Only Fans star and author Gaby Herstik, who center their practice on a celebration of sensuality and Sex Magick. The archetype of the witch as nymph and seductress is one that has endured for centuries, the innate power of female sexuality eliciting fear and oppression from medieval Christian society. Sexuality was synonymous with shame.

With the modern practice of Sex Magick, the intention is to move through shame and transform sexuality into self-empowerment. “I’m fascinated by the shadow self, by sexuality, kink,” says Herstik, “and I’m an exhibitionist so I use social media as a kind of performance art.” In her latest book, Sacred Sex, Herstik offers tools to “shed societally ingrained shame and reclaim your birthright to sacred sex as a foundational part of your spiritual path.” The witch, for Herstik, is an archetype of feminine liberation and sensual power. She explains her practice as integrating various traditions of ancient goddess worship, specifically Venus, the Goddess of Love, integrated with aspects culled from “tantra, kundalini, Kabbalah, and Taoism.”

READ: Traditional Healers Are Growing Old Without Successors

This “everything but the occult kitchen sink” approach is common in the era of modern witchcraft. Practitioners often hone in on what aligns with them intuitively—pulling knowledge from the past, integrating elements from various Tarot and astrological traditions, experimenting with plant medicine (from herbs to psychedelics and cannabis), yoga, meditation, and other healing modalities, drawing from their own family histories, and, perhaps most importantly, from their personal search for identity and self-fulfillment.

Amanda Yates Garcia, known as “The Oracle of LA,” is a scholar, artist, and working witch. In her podcast Between Worlds, she explores astrology and the Tarot arcana in depth, as well as interviews practitioners working in an array of magical traditions. She also offers public ritual and performances, both in intimate gallery settings and at large events throughout Los Angeles. In her memoir, Initiated, Yates writes eloquently of her own evolution as a witch, from her initiation at age 13 into her mother’s earth-centered practice to her eventual personal redefinition of the archetype. For Yates, true initiation came in the form of life experience and an independent, individual choice to, as she explains, “re-enchant the world.” In her work and art, Yates promotes witchcraft not just as magical practice, but as an act of creativity and radical revolt. In Initiated, she writes, “Magic connects people to their roots, to their spiritual ancestors and allies, to the hundreds of thousands of beings who have gone before them experiencing similar struggles…magic gives you hope, magic gives you pleasure, and most importantly, magic helps you remember you have power, even if you can’t see a way to use it yet. The fact that magic connects people to their power is the main reason most systems of oppression attempt to ban it.”

As we’ve seen throughout the ages, oppression breeds rebellion. And rebellion sparks creativity, community, and empowerment. As Pam Grossman writes in Waking the Witch, “The witch owes nothing. That is what makes her dangerous. And that is what makes her divine. Witches have power on their own terms.”

And so, the archetype rises up, again and again—in times of turmoil, struggle, inequity. In this moment of change, catharsis, and upheaval, the modern witch has arrived, stepped off their broomstick, and shapeshifted into the 21st century. They stir the cauldron of contemporary culture as it boils and brews, a chalice in one hand, and a sword in the other, ready to nurture or to destroy.

*This article was originally published in DoubleBlind Issue 9.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.