Once a month Jerred Locke and Natalie Stryffeler invite friends and strangers into their 700-square-foot Seattle apartment. As many as nine people sprawled upon yoga mats overtake the living room, adorned with blankets and pillows. There is no furniture, apart from a delicately displayed collection of colorful crystal singing bowls. Many of the room’s inhabitants are regulars—they come almost every month. But, people seeking a particular kind of connection often find their way to this inconspicuous hideaway in the bustling Queen Anne neighborhood.

Locke and Stryffeler describe themselves as space holders. The practice they facilitate harkens to a more intimate style of healing, where community building comes in the form of home ceremony. Together, all of Locke and Stryffeler’s guests embark on a spiritual journey that blends sound healing, restorative yoga, breathwork, touch, and plant medicine.

But, by “plant medicine” we don’t mean ayahuasca or psilocybin mushrooms—psychedelics that are often given prime-time attention in today’s media environment. Instead, the main attraction is something far more subtle: cacao.

Most Western and contemporary consumers know cacao by its more popular name: chocolate. The famous bean is fermented and pulverized into powders and butter, and most often sold to large manufacturers who turn the plant into chocolate bars and candies that have mass appeal. However, the world of Hershey’s and Swiss Miss is only one reality of cacao. There are many, many more.

What is Sacred Cacao?

Cacao (Theobroma cacao) is a tropical tree native to Central and South America. For centuries, cacao has been one of the region’s most important agricultural crops, taking a close second to corn (maize). Its seeds are used to make chocolate, which not only contains a host of minerals, fatty acids, and energizing caffeine, but also the feel-good chemical theobromine.

To prepare cacao for use, farmers harvest ripe cacao pods from adult trees. They then crack open the pods, remove the white beans inside, and allow the raw beans to ferment for roughly one week. During fermentation, the beans transform from white to brown. Then, once fermentation is complete, cacao beans are left to dry. Once dry, they can be consumed in their raw form or processed further into chocolate products.

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

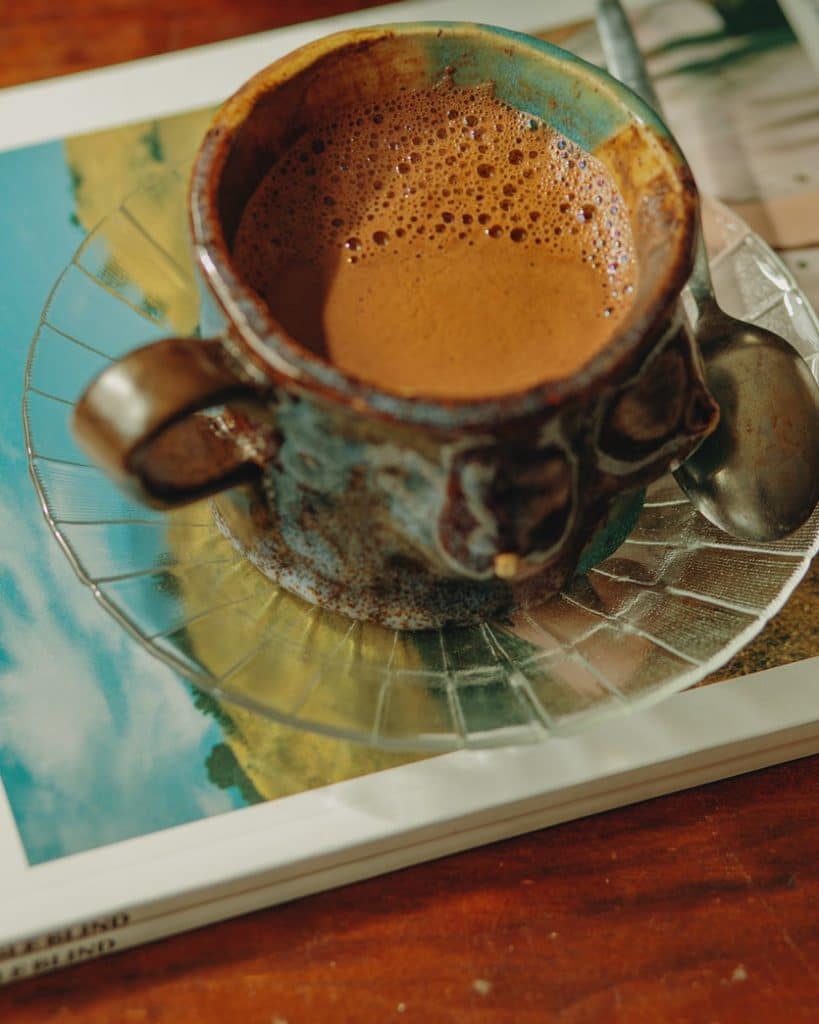

Most chocolatiers buy cacao, roast it, and transform it into cocoa butter. Cocoa butter is the base for almost all chocolate candies and snacks. But, historically, chocolate was enjoyed as a drink long before it was transformed into candies and cakes. Across Latin America, the birthplace of chocolate, cacao was (and still is) brewed into a rich, bitter, and nutrient-dense beverage.

“Granny always prepared a special cacao drink to have in the afternoon, to drink after school,” says Dr. Rocio Alarcón. “A hot, delicious beverage. This is not processed chocolate, it was pure chocolate, and this is how all the grannies and all the mothers [prepared cacao] when we arrived from school to give us the energy to keep doing homework.” At least, this was how women around Quito and the rural area used the plant, she articulates.

Alarcón explains that cacao is important for women 40 days after childbirth: “The power to be in contact with cacao again for the energy that is going to help the mother’s milk.”

Dr. Alarcón is no stranger to tradition. She self-identifies as Mestizo, which means that she comes from both indigenous and Spanish heritage. For her, continuing to study and protect the plants and herbs of the Amazon is a way to continue to preserve the traditions passed down by her grandmother, great grandmother, and the heritage that came before.

It’s this heritage that inspired Alarcón’s work as an ethnopharmacist, ethnobotanist, and shamanic practitioner. For the past three decades, she’s dedicated her life to preserving the rich biodiversity and cultural heritage of the Ecuadorian Amazon. She does most of this work through her nonprofit organization, the lAMOE Center, which protects a 100-acre buffer zone before the Yasunί National Park in eastern Ecuador. 257 different species of trees and shrubs grow on the land, cacao included.

Where Does Cacao Come From?

But, cacao’s exact genetic origins are somewhat of a mystery. The plant is native to South and Central America, yet scholars debate whether the plant first came from the Amazon and traveled upward, or if it’s native to Central America and traveled downward.

What is more certain, however, is that the tree has been cultivated and traded around Latin America for millennia. Some of the oldest evidence of cacao beverages dates to 1100 BC. Archeologists found traces of theobromine, the bean’s primary active constituent, in pottery excavated in what is now Honduras. To scholars’ knowledge, the plant’s history spans many of the great Latin American civilizations: the Inca, Aztec, Maya, and Olmec.

It’s also a plant that Alarcón calls a “Master Plant.” As a Master Plant, cacao has one unique feature: It’s ubiquitous. Indigenous peoples traded the plant heavily prior to Spanish colonization, cacao made its way as far north as modern-day New Mexico and as far south as Peru. Cacao, like tobacco, became popular amongst Europeans after colonization.

And the plant withstood the test of time. Today, cacao is among the world’s top 100 cash crops. As much as 70 percent of the world’s supply is now produced in West Africa, with Côte d’Ivoire producing more than any other country.

What is a Sacred Cacao Ceremony?

It’s difficult—and arguably not the place of—any Western writer to explain the episteme of another culture. But, it is important to place different worldviews in context in an effort to better engage in dialogue about our own culture. So, as Mayan activist Rigoberta Menchu explains best in her testimonial biography, “every part of our culture comes from the Earth. Our religion comes from the maize and bean harvests which are so vital to our community.”

In the United States and other colonial contexts, ceremonial cacao (sacred cacao) is most often attributed to Mayan, Aztec, and modern Nahua cultures of Mesoamerica. Cacao is used in ceremonial and celebrational contexts by some of these cultures, especially at weddings, births, baptisms, funerals, and religious gatherings.

Cacao is also used as an offering to God in some Mayan traditions, especially in relation to agriculture and the protection of the land. And the plant’s history is deep-rooted—cacao is also a part of some Mayan and Aztec creation stories. Some Mayan and Aztec groups hold the belief that humankind was created by deities from maize, cacao, and sometimes other plants. In the Aztec empire, cacao was also used as currency.

But, Mayan and Nahua cultures—which together constitute more than two dozen different ethnic groups and who speak different languages—are far from the only communities that use cacao. Among these cultures, cacao is not reserved exclusively for ceremonial use. Rather, it’s sometimes used in specific ceremonies, and it’s sometimes not. Cacao, like maize, is a staple crop that holds a multitude of meanings amongst Mayan cultures: It’s food, it’s medicine, it’s blood, it’s a livelihood, it’s an offering, and it’s a divine gift.

“For us, especially for people who live in the middle of the Americas— we are a culture of pioneers with cacao,” explains Alarcón. “Pioneers in the sense that, for thousands of years, we have managed this plant.”

Alarcón herself is not Mayan. But, her home country of Ecuador is thought to be one of the birthplaces of the cacao plant. While some of the first evidence of human interaction with cacao comes from Mesoamerica, the equatorial climate of Ecuador is a haven for cacao trees. Recent genetic research suggests that the first cacao trees came from the region where the Amazon basin meets the Andes mountain range.

Alarcón tells DoubleBlind that cacao iconography can be found in pottery that dates back 5,000 years, showcasing “goddesses and gods offering the black seeds to humanity.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

She continues: “So, what happened to the descendants of those people? We received that message from our ancestors. For us, cacao is not a ceremony, it’s our daily way to have contact with the plant […] All this is a part of that culture, of that legacy. So, for us, we don’t need to think ‘okay, we need to go and do a ceremony now.’ It’s part of our daily life.”

“Drinking cacao was a way to be in contact with the plant,” she says, “to be in contact with foods, and to obtain energy for the brain, to help us emotionally, to help us physically.” In the Ecuadorian highlands, mixing cacao with cheese, she says, is something she grew up with as a child. “It’s part of our culture.”

“But, that was in the highlands,” she continues. “Of course, in the coastal region or in the Amazon, there are different ways to prepare the cacao. And we all know that.”

What Happens During a Cacao Ceremony?

So, if cacao is used by a variety of different cultures, what exactly happens during a cacao ceremony, anyway? Well, that’s a good question. It depends entirely on the culture and community performing the ceremony, the purpose of the ceremony, and the time the ceremony is performed. How cacao is used ceremonially is different for each culture using cacao; it may be incorporated into a baptism, used as an offering, or, as Alarcón articulates, ingrained into a daily way of life.

Nevertheless, cacao ceremonies have quickly become popular in the West, especially among alternative health and healing circles. But, it’s important to point out that these ceremonies are, more often than not, wildly different than what is practiced by many indigenous cultures. In most Western cases, cacao incorporated into ceremonial experiences that are entirely new, experiences that may draw from numerous modalities and from numerous different cultures, all melted and blended into one experience.

“That’s something that we will often say to people,” says Locke. “The practice that we’re sharing is simply our own practice. That would be us diving into our own medicines, finding what fits us and resonates with us. We simply share almost exactly the practice that we do ourselves.”

Locke and Stryffeler draw upon their training in restorative yoga, breathwork, and other alternative healing techniques to create an all-inclusive space for people who want to engage with a community holding space for spiritual practice. And the practice is always different. Sometimes it includes journaling, it always includes lots of breathwork, and of course, sipping cacao.

“Part of our ceremonies is connection through the heart space,” says Stryffeler. “That is my mission on Earth. That is cacao’s mission on earth. And so that’s why I feel such a strong connection to work with this plant, to share it is because our missions are 100 percent aligned. And even if that wasn’t the main focus or what I wanted to see in my ceremony, it’s inevitable.

“If you’re working with cacao in a sacred space, you’re going to be in your heart. You’re going to be able to meet the people around you, heart to heart. And one of our favorite ways to just kind of facilitate that experience is through breath work, as a catalyst. The cacao really activates the breath and the breath also activates the cacao. You have these two medicines that become even more alive when they’re dancing together.”

Stryffeler explains that some of their ceremonies are more interactive than others. “You’re in small groups with other people. You’re placing your hand on someone’s heart, your soul gazing with them, and you’re really connecting with them on a deep level.”

“It’s not just an experience,” says Locke. “This is a community we’re building. So we changed the name to community breathwork session. That’s just what it is. Community breathwork. We’re coming to you and we’re doing this practice that everybody shares. […] It’s in our home. It’s personal. It’s connected.”

Tough Conversations About Sacred Cacao and Cultural Appropriation

Without a doubt, Locke and Stryffeler have created a compassionate and welcoming space for people to engage with the spirit of cacao. But, the use of cacao in yoga and other non-native practices is not without criticism. There may be no “proper way” to conduct a cacao ceremony, since the drink is often incorporated into other celebrations rather than necessarily “worshiped” on its own accord. Second, different indigenous communities each use cacao in their own unique ways. And finally, while cacao has important cultural value, it also is simply a part of daily life for many people—it’s part of an episteme, an entire body of knowledge and worldview that extends far beyond the ritual use of just one plant.

One of the biggest criticisms of Western cacao ceremonies centers on cultural appropriation. Appropriation is the act of taking something or some practice as your own, without permission. Plants like cacao become trendy amongst those seeking to experience and capitalize on native traditions. Yet, historically, very little of that capital makes it back to the land and the communities from whence the plant originally came.

To further engage this conversation, DoubleBlind spoke with Jamilah George, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Connecticut. George studies psychedelic therapy as a potential treatment for racial trauma. Racial trauma is trauma that’s caused by the everyday impact of racism, including microaggressions, systemic bias in the law, interpersonal violence, physical violence, as well as the inherited burden of a history saturated by the violence of police brutality, slavery, and colonialism.

“In the Western context, it’s really easy to say that you have found something and you claim it and then rename it or, you know, kind of restructure, reorganize it such that it was yours as if it was yours to begin with,” says George. “In [the United States], we have a long history of that. Whether it’s claiming physical bodies and bringing them from Africa to this country and claiming them as theirs and saying that we own you, or whether it’s the land, taking over the land [that belonged to] natives that were already here and renaming it and claiming it as if it were theirs.”

“There’s this painful, deep-seated legacy of theft,” she says. “And we don’t talk about it. It’s uncomfortable. And so we just kind of try to pretend like it hasn’t happened.” Opening up true and honest communication about cacao is an essential step in acknowledging that legacy.

“We make it very clear that we bring up its history,” says Locke. “The fact that cacao is a stolen plant, that cacao is a spirit that has been cared for by hands that were essentially slave labor, labor or child labor even.”

What Locke may be referring to is the 500-year history of Latin American colonialism. Cacao was quick to impress European colonists after Columbus’ arrival to the Americas. He brought cacao beans to Europe in the early 1500s, beginning the first global chocolate trade. The arrival of the Spaniards and Portuguese in the Americas triggered a centuries-long exploitation of people, land, and natural resources. Spaniards took gold, tobacco, cacao, and other valuables while overtaking the Aztec empire. In the midst of conquest, many indigenous idols, buildings, and textiles were destroyed, disappearing many written and artistic records of indigenous spirituality and culture.

But, these exploitations certainly are not limited to the colonial period. In the 1950s, for example, the American-owned United Fruit Company held exclusive rights to Guatemalan banana production, as well as telephone, telegraph, and most rail lines. The monopoly held by the United Fruit Company was threatened in the 1950s by Guatemala’s second democratically-elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, who redistributed the corporation’s unused lands to landless farmers.

Although UFC was compensated for the land, the company still lobbied the U.S. government for intervention in Guatemala. The American government, with the help of the newly formed CIA, backed the regime of Carlos Castillo Armas, the same regime that triggered Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, resulting in a genocide against the country’s Mayan communities. While bananas were the United Fruit Company’s main crop, this legacy of foreign intervention, control, and resource extraction is very much alive throughout the region.

“We will bring up these facts and we’ll invite in this energy of healing cacao’s spirit from years and years of abuse by capitalism and other people,” says Locke. Locke and Stryffeler host their cacao ceremony on a donation and sliding-scale basis. This is quite different from the $40 to $50 fee that’s required to experience cacao ceremonies at studios and event spaces across the United States.

The Spirit of Cacao

Many people share the belief that plants like cacao should not be incorporated into Western spiritual practices, especially when these practices are led by practitioners who have little or no connection to the indigenous heritage of the plants. But, completely removing the spiritual when engaging with these plants comes with its own set of problems—like reducing the value of entheogenic plants to merely their active chemical constituents.

“These medicines were discovered for spiritual transformation as a means to connect to a higher power, a higher being, and then also to do that in community with others,” says George, speaking generally of psychedelic medicine.

Recent scientific studies of psychoactive mushrooms offer a good example of this phenomenon. In scientific research, the active component, psilocybin, is extracted from mushrooms to use in clinical trials. In Mazatec tradition, however, the psychedelic experience inspired by psilocybin mushrooms is inseparable from religious practice: Making a distinction between the two is impossible.

Spirituality and science should coexist, says George. “This idea that there is a binary, I think that that’s a false construct. And for Western folks, that’s uncomfortable because we’re not historically a spiritual people. But, indigenous people are people of color are. So, that spirituality piece is really crucial to all of this work.” And that work includes using plant medicines to heal from racial trauma and the colonial history that still influences who has access to these plants and the stories that are told about them.

“In my beliefs, plants have a spirit and they travel around the planet,” says Alarcón. “Not because we want them as humans, but plants travel from different place to different place, through the birds, animals, and, of course, humans.”

“People bring the cacao [into their lives] and add extra qualities to the cacao; that is how the plant engages with people. Even in the United States or in other countries, adding extra things [like cacao ceremonies] is part of the needs of that culture,” says Alarcón.

Stryffeler shares a similar sentiment. “I think plants have spirits and that they’re more intelligent than us,” she tells DoubleBlind. ”Cacao has chosen to make this huge appearance popping up all over the world, becoming super popular, super trendy.”

“And I think she’s chosen us now because she sees that right now is the time that humanity is turning to the plants. The things that we’re trying before aren’t working. What we’ve been told how to heal ourselves or how to walk through the world has, you know—the way that we’ve been told to do that isn’t working. And we’re realizing that. And so we’re turning to these other sources. Cacao one of those. It’s made a huge appearance.”

Cacao and the Art of Healing Amidst Colonial Legacy

Looking at different interpretations about plants and the values we place upon them is like holding a mirror to ourselves. “We realize now that there is not a single world, but many worlds, each with its own internal logics, and which must engage with each other despite a multitude of different understandings and objectives,” writes psychedelic researcher Sarai Piña.

And an integral step toward equity is acknowledging and taking steps to rectify harm. “My plea to my white brothers, sisters, and my gender-conforming family is to recognize your role in cultural appropriation to recognize your white privilege and to denounce it,” continues George. “And then to go a step further and be intentional about including people of color, especially the people of color from which you have borrowed, such that you have had beautiful experiences of self-discovery, self-exploration, and self-healing.”

Western mainstream culture, including the psychedelic community, she says, needs to recognize when it’s committing acts of cultural appropriation. “The least you could do is allow the people from what you borrow to also share in that experience of healing and self-discovery,” she adds.

“Until that acknowledgment happens, these systemic racial inequalities and exclusions are going to continue to be perpetrated. The growth and the development of the psychedelic field and the ability to provide healing to those who really need it will continually be stunted. We’ll continue to make the same mistakes over and over again; we’ll be in a vicious cycle of theft and appropriation. It’s really harmful and it’s traumatic to the people in these communities.” And these communities, she says, aren’t just historical, but still practicing their traditions today.

In Alarcón’s view, we also need to protect the plant itself. “Generally, in Ecuador,” says Alarcón, “people used Mesoamerican cacao for probably over a century. But, the cacao from Amazonia just disappeared in the process.” And this disappearance is a big problem. In destroying the biodiversity of the plant, the story and heritage of the people in the region begins to change, a concept that takes center stage in Alarcón’s work in the Amazon.

Alarcón partnered with the University College of London to compare the chemical makeup of cacao from the Amazon to Mesoamerican cacao, the latter of which dominates the world’s chocolate industry. “We compared the level of theobromine in cacao from the Amazonia has the most incredible level of [this compound], and that is the beauty!” she explains. “What we need is that level of theobromine in the cacao, which makes us feel so happy and healthy. And that is the beauty of this cacao.”

Unfortunately, the biodiversity of Amazonian cacao is currently threatened by a number of different aggressors, with deforestation and commercial agriculture being the top two. While Ecuador was once home to more varieties of cacao than any other country, one-third of the country’s cacao now comes from a pervasive hybrid variety that lacks the taste and quality found in Amazonian plants.

“We need to research,” says Alarcón, “Always, we need to ask, ‘where is it coming from, this cacao? What is the combination, what is suitable for my body?’” People need to interrogate its quality, chemical composition, and the company offering it.

Buying from indigenous-owned businesses, supporting co-ops and small farmers, buying rare or heirloom varieties, supporting land conservation, and researching your materials are all ways to help cultivate equity in the cacao trade.

As Locke says best, “[Cacao] is here to heal you, but we’re here to heal her as well.”

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.