Travis’s* whole world was his ayahuasca community. For five years, he attended ceremonies, working his way toward becoming one of the group’s core members, known as a “guardian.” He’d ensure no one wandered off mid-ceremony, provide energy work, clean peoples’ buckets after they purged, walk or carry people to the bathroom, and assist ceremony participants and facilitators in any other way necessary.

“The community was my life,” Travis said, who joined the group in 2015. “We spent a lot of time together, not only in ceremony and working together in that capacity, but also doing all kinds of other things. I really trusted the people in this community with my life.”

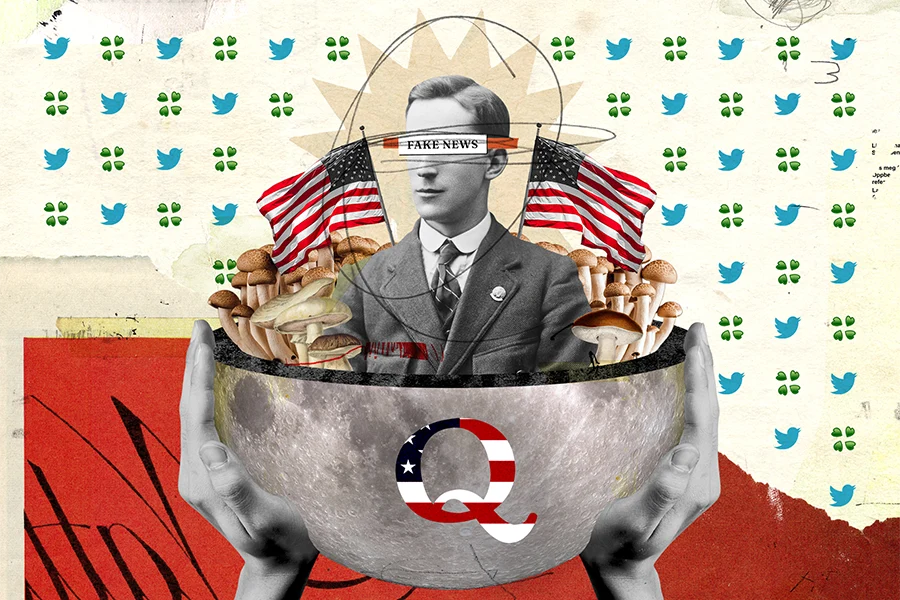

Then, Covid plunged the world into crisis. By April 2020, one leader began posting on Facebook about masks being a mechanism of governmental control and denying the existence of Covid. By May 25, 2020, the day a Minneapolis cop murdered George Floyd, the community leader posted that it was a false flag. Pretty soon, that leader’s Facebook page became a melting pot of QAnon-adjacent conspirituality, and it colored the conversations between community leaders about the ethics of holding ceremony amidst a pandemic.

“There were a bunch of us who stopped attending ceremony,” said Jade*, who was part of the community for five years. “But there were a few people who were anti-vaxx and Covid-deniers who continued going, which was a statement around their values. Then people started posting and talking about Covid safety, vaccines, and Trump—it was like a snowball effect of conspiracy theory, that inevitably caused people to start taking sides.”

Jade was disappointed, but not surprised by the community’s reception to conspiracies; she had noticed and become disillusioned with aspects of the community prior to 2020. Travis, however, felt gaslit and let down by the group. The people he thought he knew were instantly strangers. “The change happened so fast,” he said. “We were a very environment-focused group and on the same page about how we can better the planet. It went from that to posting about [big-name environmental activists] working for George Soros. We were like, ‘What the fuck is happening?’”

The leading community members held multiple meetings about the obvious division. One faction of leaders was in defense of the fringe beliefs and couldn’t fathom how the others remained “asleep” to what was happening. The other hoped to eject the community’s loudest conspiracists, one of whom was described as going from a “super chill and awesome dude” to ragefully expressing “far-right, anti-gay, anti-trans, and anti-immigrant” beliefs despite the community containing people with all of these identities. The lead facilitator ultimately decided to maintain the community’s status quo, causing Travis and several other guardians to leave indefinitely.

What happened to Travis and Jade’s community isn’t an isolated incident. Conspiracy theories rocked the psychedelic ceremony world, especially in the early days of the pandemic, leaving many people disillusioned with the people and cultures they thought they knew. But given that most of the pandemic’s conspiracies du jour are dog whistles for bigotry and harmful politics, how did a culture of people deeply involved in healing trauma, love and light, and making the world a better place suddenly become a breeding ground for iconoclastic ideologies?

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

There are many prongs to this answer. Perhaps the most straightforward is that conspiracy theories commonly proliferate during times of societal crisis and uncertainty. It happened after 9/11, the AIDS epidemic, JFK’s assassination, World War II, the Great Depression, the Spanish Flu, World War I, and even the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64. It checks out that a tsunami of conspiracies wreaked havoc on communities and relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. People contrive theories as a way to make sense of jarring events or perceived alliances, to create a (false) sense of stability, or to reinforce certain beliefs. It’s one of the oldest evolutionary coping mechanisms, according to “Conspiracy Theories: Evolved Functions and Psychological Mechanisms,” a study published in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

People who consume psychedelics, however, are generally more inclined to engage with fringe ideas, regardless of crisis. And it’s likely because psychedelics are products of the underground (thanks to the drug war), where unorthodox ideas proliferate. Jade believes the normalization of alternative lifestyles in psychedelic communities contributes to the germination of conspiracies. “I noticed that the people who were into natural medicine or the alternative healing arts were very susceptible to these conspiracies. They were the ones to immediately take a stand against the vaccine.”

There’s an indistinguishable overlap between psychedelics and wellness cultures. People from both camps are often motivated to seek answers for the same reason: Distrust of societal institutions. However, the inherent paranoia that comes with a lack of trust, combined with the desire to be alternative—which can take many forms—also increases the likelihood of exposure to information of questionable origin.

“Psychedelics and wellness cultures have always purported the idea, ‘You are your own best doctor, you can heal yourself,’ and ‘no one knows your body better than you,’” said Derek Beres, co-host of a podcast called Conspirituality and co-author of the book Conspirituality: How New Age Conspiracy Theories Became A Health Threat. The term “conspirituality” is a portmanteau of “conspiracy” and “spirituality,” and was coined in 2011 by anthropologists Charlotte Ward and David Voas who noticed people with New Age or alternative beliefs are prone to conspiracy thinking. “In these communities, people call [ayahuasca] ‘medicine’ and often lean anti-vaxx and believe anything synthetic is toxic and only natural is good and people grow distrustful of anything pharmacological, completely not understanding that [consuming highly psychoactive plants] is chemistry, too.”

While it’s healthy to remain skeptical of industries that profit off of illness or addiction, it’s important to remain objective and not write off science altogether. “If you don’t trust science and you don’t think you need evidence-based research, then you can pretty much believe anything,” Jade said. “You can think the world is flat and believe things are evidence-based, even when they are not.”

Conceptually, the idea of living naturally is enchanting. But natural lifestyles can become a slippery slope in communities seeking alternative ways of living. Echo chambers often emerge that inevitably lead to groupthink and perpetuate harmful ideas cloaked as spirituality or healthcare.

“There are certain aspects in the beliefs of ‘natural’ people, who believe in natural medicines, that are inherently primed for neo-Nazi beliefs,” Jade said. “I have a friend who is 70 years old who was a prominent figure in the early psychedelic movement. In 2020, she sent me this incredibly well-researched story about how communities who practiced alternative medicine and post-traditional spirituality became Nazis and supported Hitler during WW II. It fit into their ideas of purity.”

Of course, there are many liberals and BIPOC folks who live natural lifestyles and aren’t Nazis or fascists. But it’s notable that Nazis desired to live alternative, natural lifestyles steeped in mysticism. Jules Evans, writer and director of the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project, wrote a story about the Nazis’ obsession with regenerative farming, organic food, and natural medicine called “Nazi Hippies: When the New Age and Far Right Overlap” in 2020. Leading Nazi Rudolf Hess “opened a center for alternative medical practices in Dresden in 1934,” while Heinrich Himmler, another powerful Nazi, “supported alternative medicine—such as using plant extracts to heal cancer—and authorized experiments on prisoners in concentration camps for this research.” The Nazis also studied psychedelics under Hitler’s reign. “They were the first government to back psychedelic research, experimenting with mescaline on camp inmates to see if it could be used to break their will.”

Magical thinking is another characteristic of those who believe in conspiracy theories, according to a study by Evita March published in PLoS One. It can manifest as seeing patterns or connections when there are none or believing that one’s thoughts or actions can influence events in ways that defy rational explanation. The “mystical experience”—a profound spiritual encounter or state of consciousness that can be occasioned by psychedelics, fasting, meditation, or other modalities—can also lend itself to magical thinking, often through ecstatic experiences distinguished by intense states of ekstasis, transcendence, wonder, and awe. Ecstatic experiences have been marginalized in Western Culture since before the Reformation, Evans stated on the Third Wave podcast, and psychedelics offer a way for people to experience ecstatic states of consciousness. The pursuit of magic and spiritual experiences via psychedelics can morph into a quasi-religious devotion for some people.

“You might think that ayahuasca communities aren’t religious, but they can be super religious, especially if you go to the [legal] churches,” Jade said, referring to Santo Daime, a Brazilian ayahuasca church with chapters in the US. “People in ayahuasca communities sometimes interact with the medicine as if it’s a religious prophet.”

The fervent thirst for these heightened states of consciousness points to a deficiency of spiritual nourishment in Western culture. And because there’s no framework for ecstatic experiences—let alone ones fueled by psychedelics—another problem arises: Lacking critical awareness that certain insights gained during the mystical experience may not be true. Stanislav Grof, a renowned psychedelic researcher and psychiatrist, says psychedelics are “non-specific amplifiers of the human psyche,” meaning that they enhance pre-existing internal experiences, even if an individual feels like they’re having novel realizations coming from an external source. Often, people take what they experience in these moments as fact because it feels real, regardless of how strange or fringe these unveiled ideas might be. Furthermore, psychedelics also make people considerably more suggestible to their own thoughts and feelings—and to the ideas of others. Several studies in the scientific literature, authored by researchers Roland Griffiths and Reuben Kline respectively, show that psychedelics make us more open, agreeable, and prosocial. People are, thus, more likely to believe ideas that are shared with them by trusted facilitators, healers, or their social circle, especially over time.

“What happened in our community was scary because the folks who started talking about conspiracies were facilitators,” Travis said. “When they started sharing things publicly, participants who were subject to easily being imprinted upon started picking up things that they typically might not have believed. But it’s different when it comes from a healer. It became 100 percent true to them. So, [conspiracies] spread like wildfire.”

Zeus Tipado, a neuroscience and pharmacology Ph.D. candidate at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, recently wrote a story for this magazine about “neurospirituality.” Michael Ferguson from Harvard’s Divinity School discovered an area of the brain that can trigger hyper-religiosity when it’s activated, say, by temporary lesions caused by surgery. “It will cause people to join numerous churches or religions in the span of a month,” Tipado said. “This part of the brain is also activated whenever a person does psychedelics, which shows the susceptibility factor is also at play here.”

A common misconception about psychedelics is that they bestow people with liberal or progressive politics, said Dr. Brian Pace and Dr. Neşe Devenot, two researchers who authored “Right-Wing Psychedelia: Case Studies in Cultural Plasticity and Political Pluripotency,” published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. It emerged in response to the surge of articles around studies suggesting a correlation between psychedelic use and liberal ideologies, specifically anti-authoritarianism and pro-environmentalism. But psychedelics aren’t coded with political doctrines that blossom in our psyches after ingestion. Pace and Devenot trace this misconception to the cultural landscape of psychedelic use in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Because [the 60s] witnessed an explosion in countercultural fascination with widely available classical psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline,” they wrote, “Psychedelics have often been conflated with the progressive and radical politics of the moment: The sexual revolution, civil rights movement, and youth radical groups like Students for a Democratic Society or the Yippies.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

Pace and Devenot point out that far-right extremists have a rich, sordid history of using psychedelic drugs without becoming more democratic or left-leaning. Historian Alan Piper wrote a book entitled Strange Drugs Make for Strange Bedfellows about the relationship between Albert Hofmann, the chemist who discovered LSD, and Ernst Jünger, a Wehrmacht officer and censor for the Nazis in occupied France during WWII. He wasn’t technically a member of the Nazi party, but he was a staunch right-wing militant who believed liberal democracy was a threat to the national strength of Germany, according to Clive James’s essay “Cultural Amnesia.” Pace explained that Jünger refused de-Nazification after WWII and was a designated Mitläufer, or “fellow traveler of the Nazis,” someone who wasn’t formally charged with participation in war crimes but was sufficiently involved with the Nazi regime. Jünger and Hofmann held private LSD sessions together, and the officer even coined the term “psychonaut.” “From the outset, LSD has been a substance of interest to individuals of a radically conservative disposition,” Piper wrote.

Andrew Anglin, founder of the leading neo-Nazi website, The Daily Stormer (the name inspired by Nazi propaganda sheet Der Stürmer), is another far-right psychonaut. He tripped on LSD at school, regularly consumed ketamine, and tripped on psilocybin mushrooms throughout his teens before building a digital platform for extremists to congregate and organize violence, such as the deadly “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. “[Anglin] became a neo-Nazi after extensive use of psychedelics,” Pace said. “If these are supposed to be drugs to help fight fascism and authoritarianism, they aren’t working.”

Stormfront, founded by a Klansman from Alabama, is the oldest hate site functioning as a neo-Nazi organizing forum, according to Pace and Devenot. Southern Poverty Law Center dubbed it the “murder capital of the internet” because numerous “registered Stormfront users have been disproportionately responsible for some of the most lethal hate crimes and mass killings since the site was put up in 1995.” On the site, information about psychedelics sits alongside Holocaust-denial content, Covid conspiracies, Climate denial, twisted Prager University history lessons, and abominable conversations about “white genocide.”

Frederick Brennan is a free-speech absolutist whose political ideology around the First Amendment led him to build the now-defunct message board 8chan, which was eventually rebranded as 8kun. The forums quickly became a digital refuge for white supremacists and neo-Nazis (and their conspiracies), Pace wrote in “Lucy In the Sky with Nazis.” Brennan received a “download,” a term used to refer to a revelation, during a mushroom trip to create a free speech platform. It led to the birth of 8chan in 2013 and, once it was shut down in 2019, 8kun. The allure of 8chan was its anonymity. It would eventually host the manifestos of several mass shooters and became the preferred site for QAnon, whose followers obsessively combed the forum for Q-drops. 8kun was among the platforms used to organize the insurrection on January 6, 2021, according to The Guardian. Brennan has since gone to great lengths to expose his former business partners, Jim and Ronald Watkins, whom he alleges were the masterminds behind QAnon. Pace and Devenot point to Q: Into the Storm, an HBO docu-series detailing Brennan’s crusade against the Watkins, as evidence.

Starting on the fringe site 4chan, and then migrating to 8chan and 8kun, QAnon infiltrated major social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok, amassing thousands of followers. The frenzy hinged on an anonymous forum poster named “Q Clearance Patriot,” or “Q” for short, who claimed to be a top-clearance military official planning to reveal the truth about the political “deep state”—a clandestine network in the federal government working to manipulate and control government policy. Q communicated to a cult of followers through highly anticipated leaks, or “Q drops,” on these forums and used the infamous hashtags #followthewhiterabbit (referencing Alice in Wonderland psychedelia), #thegreatawakening and #WWG1WGA.

People adopted QAnon as a set of political beliefs. Its main statements purported that former president Donald Trump was working with the US military to dismantle the deep state; Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election was actually a top-secret and collaborative investigation with Trump to indict Hillary Clinton for a number of crimes; and that a cabal of powerful politicians (Democrats) and satan-worshiping “Hollywood elites” were secretly under arrest for creating and maintaining an international pedophilia ring—and drinking children’s blood.

Travis described the collective QAnon addiction as a choose-your-own-adventure game. “I started visiting these [QAnon] message boards just trying to understand what the hell was going on and to put pieces together,” he said. “It’s weird because every message was cryptic and left very open ended, as if it was a choose-your-own-adventure where they gave you this cryptic message and you made it mean whatever you wanted it to mean. It basically made everybody feel like [they were] a part of this game to figure out what was really going on. It was extremely bizarre.”

Author and journalist Erik Davis noted in a 2021 Chacruna webinar that QAnon was designed by people who knew how to create alternate realities through storytelling. It functioned similarly to video games that require players to crack clues and participate in multiplayer virtual scavenger hunts. A key distinction, however, is that when you’re playing a video game, you know it’s fantasy. “Game designers have pointed out the various game features in QAnon… Once you start playing a game, but you aren’t aware of the fact that you are, indeed, playing a game, you are basically in source hold, which means you’re brought into a sorcerer’s story.”

What’s more, QAnon has been prominently featured in the criminal indictments filed against many alleged participants of the Capitol riot, according to NPR. We know of (at least) two Q-obsessed psychonauts who were among the first inside the Capitol building on January 6th. One of them was Jacob Chancely, the man dubbed the “QAnon Shaman,” who became the mascot of the insurrection. He goes by many names, including Jake Angeli and “Yellowstone Wolf.” (He claims to be part Cherokee.) Before the insurrection, he appointed himself a “shaman,” worked with mushrooms and peyote, and offered spiritual coaching through the “Starseed Academy – the Enlightenment and Ascension Mystery School,” according to Jules Evans. “He is a big believer in using psychedelic ceremonies for mental health,” he wrote. “Somehow, all those psychedelics failed to turn him into a liberal.” Chancely was sentenced to 41 months in prison in November 2021 but was released early for good behavior this year—despite going on a hunger strike over not getting organic food in prison, leading a federal judge to grant him access to his requested meals while he awaited trial.

William Wattson was another QAnon psychedelic rioter at the insurrection. News website AL.com reported that Watson violated his probation by leaving his home state of Alabama to go to the Capitol and was among the first to enter the government building. Watson was out on $103,000 bond for trafficking charges he picked up a year earlier for possessing more than four grams of LSD and a kilo of cannabis, according to court records, Psymposia reported. A reader of Psymposia also pointed out that Wattson has a hand tattoo of the logo of an infamous dark web LSD supplier known as GammaGoblin, further pointing to his adoration of psychedelic substances. On March 9, 2023, Wattson was sentenced to 36 months in prison, according to the Department of Justice.

Derek Beres points to the lack of political participation (and, thus, understanding of how politics work) in the US as one of the factors contributing to the surge of conspiratorial beliefs within the psychedelics-wellness-yoga Venn Diagram.

“There’s this sense in the psychedelic and yoga communities that politics is dirty, and you shouldn’t participate in it because it’s a dirty process. But that’s an extremely privileged attitude. Only someone who [lives in a] democracy and doesn’t have to actually engage in [it], would be able to say something like that. A lot of people from other nations come here to escape, to actually be able to express their voice in a democratic manner. But when you swim in the waters [of democracy] your whole life, you just don’t know it exists and that very much happens in these communities.”

I asked Travis and Jade if they had made amends with anyone from their former community. Travis has made amends with several people, but even with those he hasn’t, he wishes them well. Jade is on positive terms with everyone from her former community, including those with beliefs that are different from hers. Both Travis and Jade have since joined new ayahuasca communities that better reflect their values and politics.

For her part, Jade has come to a new understanding of people who believe in conspiracy theories. “I’m in a place now where it doesn’t feel as personal,” she said. “I believe conspiratorial beliefs are the product of vast political and capitalistic forces, and I don’t hold it against the individuals who fell down the rabbit hole. It’s not entirely their fault that they got sucked into the propaganda machine. It’s wildly powerful, and if you’re not a critical thinker, I understand how you can get sucked in.”

*names have been changed for anonymity

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.