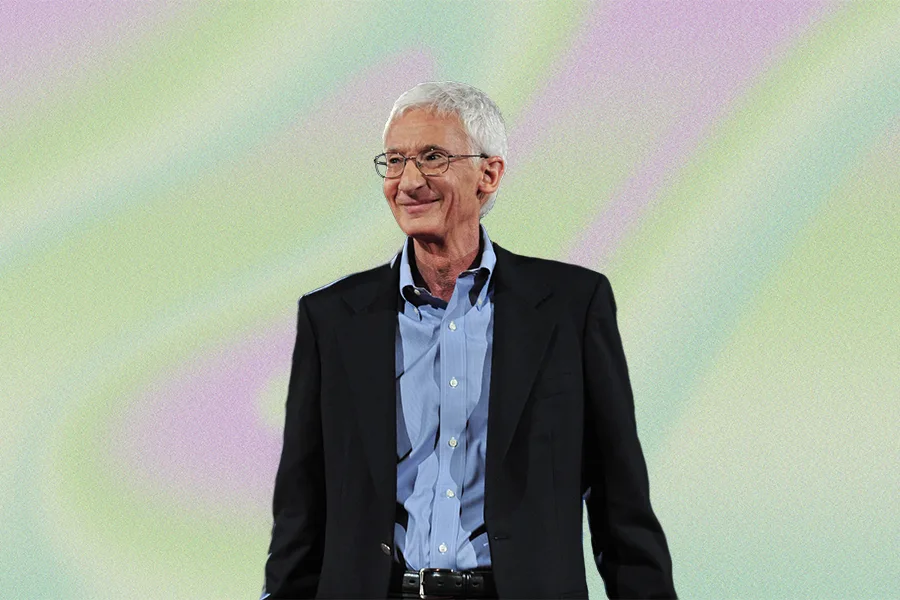

Beloved psychedelic researcher Dr. Roland Griffiths, PhD, passed away at his Baltimore home on Monday (October 16) after a months-long battle with metastatic colon cancer. Although “battle” might not be the word he would use himself. “If I had a regret,” he told The New York Times in April, “it’s that I didn’t wake up as much as I have without a cancer diagnosis. It’s been incredible.” The 77-year-old spent over two decades studying the therapeutic potential of psychedelics for end-of-life distress and other mental health ailments. His work catalyzed a new era in psychedelics research, ushering conversations about the life-altering potential of psilocybin into the public sphere. While there was some psychedelics research prior to the trials he led at Johns Hopkins University in the 90s and early 2000s, his end-of-life studies are largely credited with legitimizing psilocybin as a medicine following a decades-long halt on psychedelic science.

Griffiths founded the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at the Johns Hopkins University School. In 2000, he and his team were among the first in the United States to receive regulatory approval to study psychedelics in healthy volunteers—and approval itself is no small feat. Psychedelic research faced a decades-long hiatus following the days of Timothy Leary and the start of prohibition. “The risks were thought to totally outweigh the benefits,” Griffiths explained in his 2016 TEDMED talk, “so it seemed like a longshot at the time.”

In 2006, Griffiths’ team published impressive results: A landmark study showing that one single high-dose psilocybin session can occasion mystical experiences—moments of transcendent spirituality—in people who have never tried psychedelics before. Study participants ranked their psilocybin experiences as among the five most meaningful in their lives, comparable “to the birth of a first child or the death of a parent.”

READ: Psilocybin Therapy and the Rise of Existential Medicine

Later, Griffiths and team found that high-dose psilocybin inspired enduring improvements in mood and mental outlook in cancer patients. “Why are we wired to have these salient, felt to be sacred, experiences of encountering ultimate reality? Of the interconnectedness of all people and all things?” he asks his TED audience. “Just reflect on the mysterious truth that if you direct your attention inward, you become aware that you’re aware. An indisputable and profound inner knowing arises that we can all access individually and perhaps collectively. I think this inner knowing is at the core of our humanity.”

Griffiths learned he faced his own terminal diagnosis after a routine colonoscopy earlier this year. But, despite the weight of the news, he didn’t stay silent. In the months ahead of the end of his life, Griffiths openly shared his wisdom and learnings with the public. “I had contemplated my own death, but I had no real sense of how I might respond to a diagnosis of this sort,” he told Oprah Daily in June. “I can’t quite explain it. What occurred was this incredible opening, awakening, if you will, to the preciousness of life. And it immediately became something to celebrate.”

His long-standing practice of Vipassana meditation, which comes from Buddhist philosophy, helped Griffiths find peace. “That practice—and some experience with psychedelics—was incredibly useful because what I recognized is that the best way to be with this diagnosis was to practice gratitude for the preciousness of our lives,” he told the New York Times. “I want everyone to appreciate the joy and wonder of every single moment of their lives.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

He is survived by his wife, Marla Weiner, three children, five grandchildren, and siblings.

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.