“Tripper lore” is how illustrator Brian Blomerth describes the chronicles of R. Gordon and Valentina Wasson, a married couple of amateur mycologists, who encountered psilocybin in the early 1950s and later popularized “magic mushrooms” in the U.S.

“It’s always told in a confusing way because the story is confusing, because life is confusing, because psychedelics—and particularly mushrooms—are confusing,” says Blomerth, who recently published a book on said lore, Mycelium Wassonnii, using his Isograph pen and lush watercolors to distill an intricate, confounding history into one about love.

It’s a tricky tale: the Wasson couple’s relationship to psychedelics is profound, but not as clear-cut as that of Albert Hofmann’s—the subject of Blomerth’s previous book on Bicycle Day, the chemist’s first intentional trip with LSD, which he also discovered. After all, the Wassons did not invent magic mushrooms, which have been around for millennia. They did, however, dedicate their lives to the fungi, as well as become some of the first American residents to visit the Mazatecs in Mexico and witness a psilocybin ceremony.

But the arc of their journey, leading to an infamous article R. Gordon Wasson wrote for LIFE Magazine about Psilocybe cubensis, is a winding and maze-like picaresque. The saga involves countless characters, multiple cross-country expeditions, interwoven histories and cultures—ranging from Valentina’s Russian roots, to indigenous rites and rituals in Mexico—and, not to mention, some shadowy (albeit inconsequential) influence from the CIA.

Read: Gold Cap Shrooms: What You Need To Know

To even attempt a summary is to get stuck in a web. Take for example, how Wasson ended up in the Mexican cloud forests, where he witnessed the Mazatecs in ceremony with psilocybin fungi. The ordeal getting Wasson to this point resembled a game of telephone, launched by a correspondence with writer Robert Graves, who told Wasson about the Mazatecs’ mushroom use, followed by a connection with linguist Eunice V. Pike, who referred Wasson to a guide he should travel with and who finally connected him to a shaman—who then let him observe a ceremony, but not partake in the sacrament. It would take another few years of research and a second visit to Mexico before Wasson even experienced the mushrooms’ psychedelic glory firsthand.

To make things hazier, the Wassons also published numerous tomes on their mycology findings, which Blomerth describes as “crazy because, like the gospels, all the Wasson books contain a different version of the same events with slightly different details added. It’s very wild.” In other words, more tripper lore, rather than a clear or linear history.

And so Blomerth, using his signature dog-ified depictions of humans, aimed to “keep this one highly simple.” Compared to Bicycle Day, his new book “involved so much more research, and was so much more complicated, and had so much more information I had to try and convey, that, really, I just thought the mushrooms would want it to be as simple as possible.”

How to Grow Shrooms Bundle

Take Both of Our Courses and Save $90!

So how does this simplistic approach translate a multiplex history to the page? And how do you portray something as ineffable as a mushroom trip using pens and ink?

Blomerth skips the annals of mushroom antiquity—no overt mention to the “Stoned Ape Theory” here. Instead, he goes straight to how Valentina first got her husband to embrace fungi by foraging together in the Catskills during their honeymoon. (R. Gordon was convinced that toadstools were poisonous until Valentina ate one in front of him.) He also wastes little ink on Wasson actually tripping, which didn’t occur until a later visit to the Mazatecs. The ultimate LIFE Magazine article, which is often considered the catalyst for psilocybin permeating the American zeitgeist, is mostly glossed over, too. Rather, the narrative puts the spotlight on the Wasson duo’s relationship and how their bond was cemented by a shared obsession with mycology.

“It’s cheesy, but the love basis underneath this story about psychedelics is what attracted me,” Blomerth says. “It’s highly wild that what was essentially a fun couple game—researching mushrooms—ended up popularizing psychedelics to people like Timothy Leary and many others. It’s basically like seeing the butterfly do a little flap, you know?”

Read: Bicycle Day: Demons, Milk, and “Medicine for the Soul”

And whereas Bicycle Day dedicates pages and pages to Hofmann’s acid trips, Blomerth thought it would be more interesting here “to sideline the tripping and focus on the Wassons more,” such as how their mycophilia evolved from casual curiosity to a lifelong passion. “As far the psychedelia, this book is more of a side-step instead of a jump.”

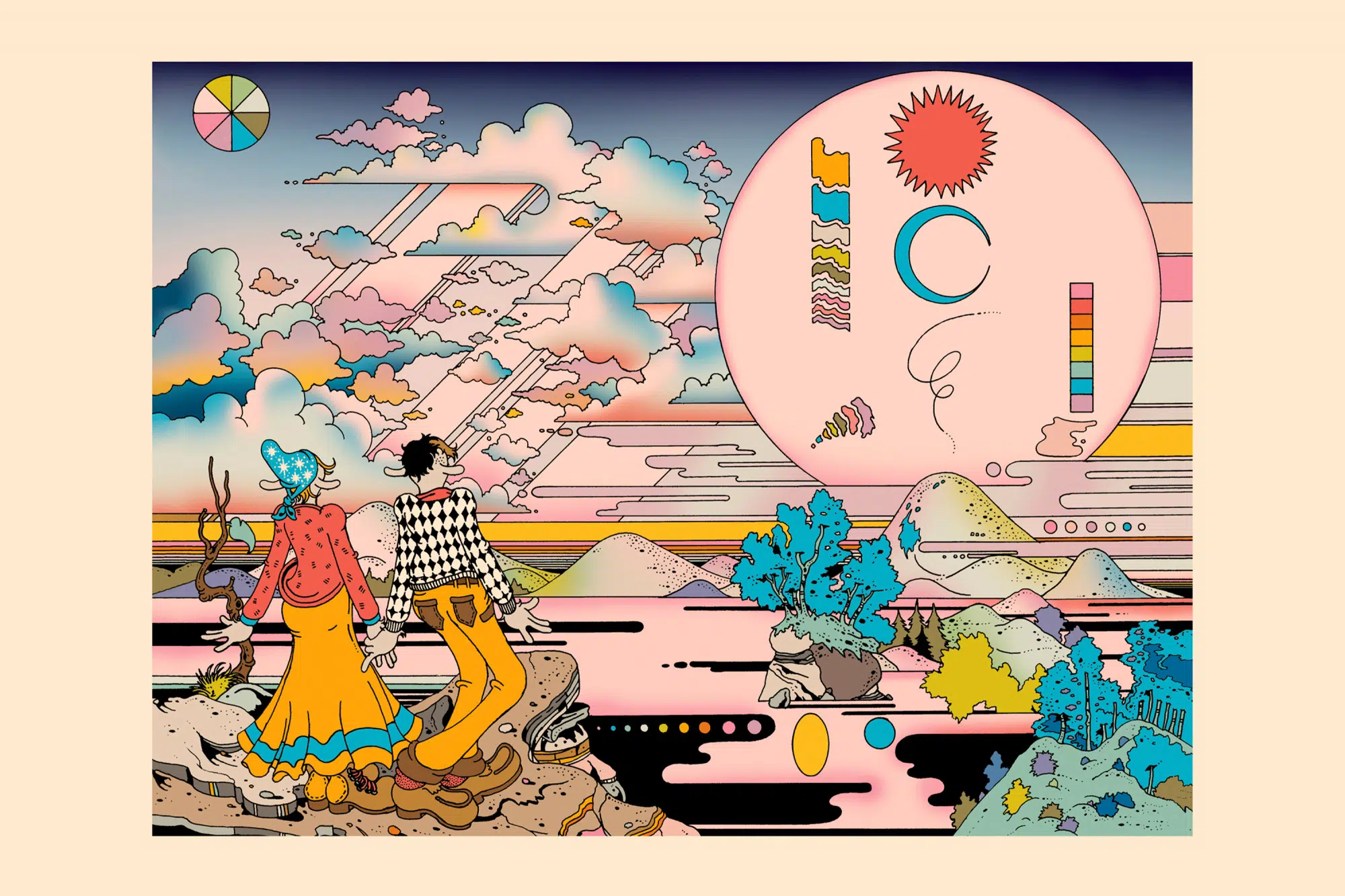

That’s not to say Mycelium Wassonii isn’t a brain-bloomer, though. Every page is splashed with pupil-dilating colors, an overload of naturalistic imagery, and countless depictions of fungi (which, in a Blomerthian flourish, “speak” via speech bubbles filled with a self-created alphabet that is actually translatable). And for the Mazatec mushroom ceremony sequences, he utilizes watercolors—which mimic real paintings made by one of Wasson’s travel companions, Roger Heim—to add an impressionistic and mystical flare to the storyline.

The effect is that the reader is “pulled in and pulled out, pulled in and pulled out” of the psychedelic vibes, Blomerth says, similar to how one can easily slip in and out of visual hallucinations during an actual mushroom trip. “I was thinking about the emotional arcs that mushrooms have, versus the in-your-face dance of acid,” he adds. “Like more of the games, the in-and-out weirdness, more of the fucking cosmic joker thing that Terence McKenna always talks about.”

In another zag from his previous book, the color palette in Wassonii is different, as well. Bicycle Day used neon pantones, since neon was developed around the same time as LSD. “Acid is a chemical, it’s lab-made, and therefore slightly unnatural—so neon fits,” Blomerth says. “Mushrooms, however, have been with humanity forever. They are part of nature. And watercolors traditionally are made with natural pigments; they’re made with all the natural world.”

DoubleBlind is a trusted resource for news, evidence-based education, and reporting on psychedelics. We work with leading medical professionals, scientific researchers, journalists, mycologists, indigenous stewards, and cultural pioneers. Read about our editorial policy and fact-checking process here.

DoubleBlind Magazine does not encourage or condone any illegal activities, including but not limited to the use of illegal substances. We do not provide mental health, clinical, or medical services. We are not a substitute for medical, psychological, or psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, or advice. If you are in a crisis or if you or any other person may be in danger or experiencing a mental health emergency, immediately call 911 or your local emergency resources. If you are considering suicide, please call 988 to connect with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.